Great Read: In Bell, a blossoming of the arts in a ‘garage salon’

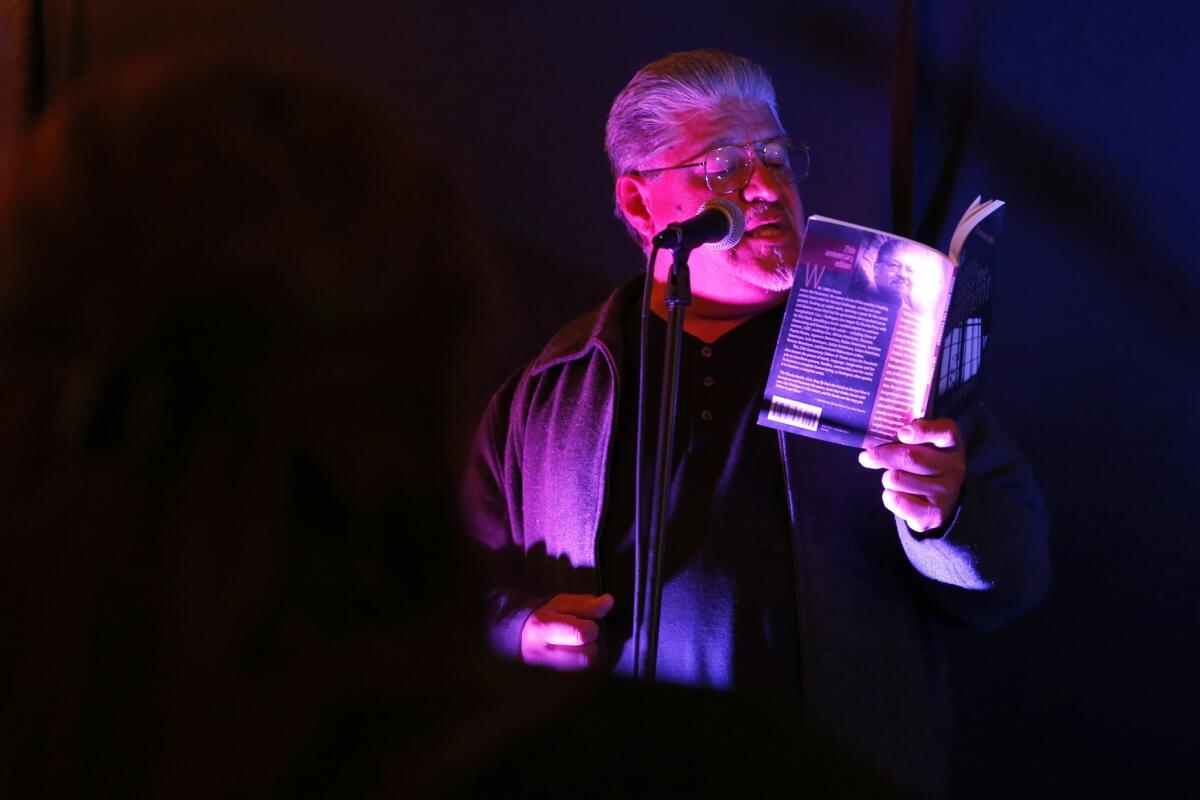

Standing on two wooden pallets covered by a floral rug, author and Chicano activist Luis Rodriguez reads a poem to more than 100 people crammed into a chilly, concrete-floored performance space.

“Here you have a way. Here you can sing victory. Here you’re not a conquered race, perpetual victim — the sullen face in a thunderstorm.”

Cellphones light up as people take photos as Rodriguez speaks, occasionally causing the microphone to squeal.

Nearby, the evening’s host, Eric Contreras, strokes his lower lip, nods and looks around the packed room.

Tonight, his parents’ garage is a cultural center.

For the last three months, musicians, painters and poets throughout southeast Los Angeles County have traveled to Contreras’ garage for an open-mic night called Alivio, the Spanish word for relief.

Contreras started the “garage salon” out of a basic need: to promote the arts for the working-class cities that line the 710 Freeway — in particular Bell, a city known more for corruption than culture.

“We always have to extract ourselves from our own neighborhoods to get any form of good entertainment,” Contreras says. “We always need to leave to Echo Park and downtown L.A., and that was a big frustration.”

Rodriguez, known for the book “Always Running: La Vida Loca: Gang Days in L.A.,” says performing at the space meant a lot to him. He used to live in the southeast, and he once lived in his mother’s garage.

“That’s where I did my first poems, that’s where I painted murals,” he says.

So when Contreras asked him to perform, he didn’t hesitate.

“I had to see it for myself,” Rodriguez says. “I think I’ve been to open mikes almost everywhere, but I’ve never done one inside someone’s garage.”

::

Contreras, a 25-year-old substitute teacher in the Long Beach Unified School District, feels a deep connection to his community, where residents have struggled economically and been caught up in a scandal not of their making.

The two-square-mile town of about 37,000 made headlines in 2010 when it was revealed that city leaders had some of the highest salaries in the nation. The scandal led to protests and recall elections, and several of the officials involved were arrested and charged. All but one were found guilty and are awaiting sentencing.

“The thought of my community — where most residents live under poverty and are immigrants — being exploited by corruption made me furious,” Contreras says.

He became politically active as a teenager, organizing a protest against a bill in the U.S. Senate that would have made it a felony to enter the country illegally and penalized anyone assisting undocumented immigrants.

Contreras said the bill hit close to home. His parents had entered the United States illegally. His mother, now a citizen, and his father, a legal resident, were supportive.

“It was very meaningful to me,” Contreras says of the protests. “A lot of kids were walking out because they wanted to ditch, but I was doing it for my parents.”

::

The idea for open-mic night came after a conversation with a friend and poet in downtown Los Angeles.

Sitting in a brown chair in his garage one recent afternoon, Contreras, a slender man with short black hair, scruffy beard and brown eyes, recalls the conversation.

“I told her: I want to do this. Our community lacks culture, art, open mikes; we don’t have plays, we don’t have museums, we don’t have anything,” Contreras said. “She said, ‘Do you have a backyard?’ — yeah. ‘Do you have a garage?’ — yeah. ‘There’s your space.’ And that’s when I thought to myself, ‘Could I do something in my garage?’”

The first two Alivio gatherings drew between 60 and 70 people. The most recent brought more than 100, mostly from Bell, Maywood, Cudahy and Huntington Park. Snagging Rodriguez, a well-known author, was considered a coup.

Rodriguez, who is also running for governor as an independent, said spaces like Contreras’ garage are important for places that are culturally barren. It’s why he co-founded Tia Chucha’s Centro Cultural, a bookstore, performance space and workshop center in the northeast San Fernando Valley.

“Five hundred thousand people living in the northeast Valley — mostly Mexican, Central Americans, working-class — and there was nothing,” Rodriguez says. “You couldn’t find a movie house, a bookstore, and you couldn’t find an art gallery.”

The Bell garage shows are generating a growing following of young people who see them as an important outlet amid what some see as a cultural blossoming in the southeast.

Among them is Damaris Pereda, 26, who is giving up her teaching job next year to help create a southeast collective to develop a cultural center in the region.

“It was because of meeting people at Alivio that I realized I wasn’t the only one with this vision,” she says. “We want a community space and incorporate culture, art and really present the beauty that’s already here.”

Denise Rodarte, who owns a vintage clothing store in Maywood, hosted two art shows at her shop last year. She’s planning on hosting a third and wants to create an art walk with the help of Contreras and Pereda.

“It’s our responsibility as a community, as activists or just residents, to take it upon ourselves and change the city and build what we want to build,” she said. “We’re starting from scratch. The corruption came, the house of cards collapsed … but what’s next and what can we do as people? You have a community that’s hungry for change.”

The popular events also led Contreras to host biweekly open-mic nights at Corazon y Miel, a trendy restaurant in the city.

Some Bell council members have attended the events and say they’re impressed by the size of the audiences. They say the gatherings are good for the city and the southeast.

“I hope it grows and fosters, because people can talk about community interests and civic engagement can grow out of it,” Bell Mayor Nestor Valencia says.

::

Alivio is a collaborative effort, Contreras says. People have donated a bookshelf, chairs and food, and some offered to lay concrete on a recent Sunday morning to even out the garage floor in preparation for Rodriguez’s arrival.

Contreras’ parents sell homemade food and T-shirts to help recoup the cost of the events. People also donate.

“We definitely need the effort from people to make this happen,” Contreras says.

At the garage on this evening, sage incense burns during performances. A man sings a Spanish Civil War song popular among anarchists and a woman reads poetry from her elementary students. Another woman reads a poem about being in love, and Contreras recites one about his childhood:

“The world will not happen to me, I am happening to this world. I am the energy of love that’s lived in the souls of millions. I am the difference.”

Just before 11 p.m., Rodriguez makes his way out of the building as Contreras starts to thank the artists, his parents and the audience for their support.

When the event ends at 12:30 a.m., about a dozen people help put away fold-up chairs in the garage. In the driveway, pamphlets about domestic violence and environmental rights are removed from a gray plastic table.

In the garage, artwork from painters and photographers is still hanging on the wall. Cumbia music is blaring from the speakers as some people talk or dance under the fairy lights hanging on the bare wooden beams.

Beneath the dancing feet, a word is etched in large cursive strokes: Alivio.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.