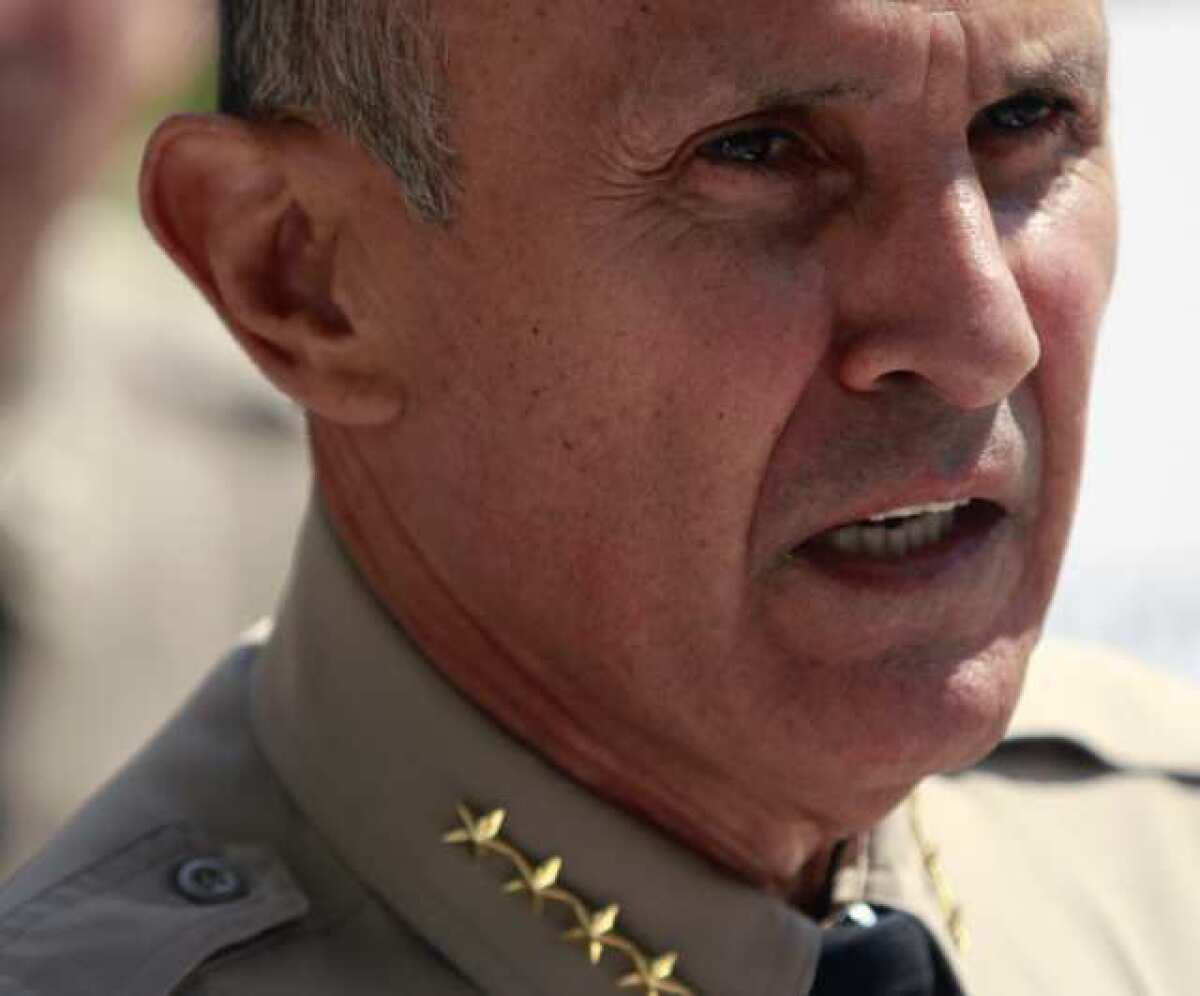

Baca facing hardest test of career

Facing severe criticism of his leadership, Los Angeles County Sheriff Lee Baca finds himself confronting his toughest political test since he took the helm of the nation’s largest sheriff’s department nearly 14 years ago.

A damning presentation by investigators to a county commission examining jail violence depicted Baca as a disengaged and uninformed manager who failed to prevent abuse of inmates by jail deputies. Federal authorities are investigating his department, including whether his deputies brutalized prisoners and harassed minority residents of the Antelope Valley. And the sheriff is facing growing political pressure to overhaul his jails and revamp his senior management team.

“The sheriff should be sweating an awful lot of bullets,” said Supervisor Gloria Molina. “This is his come-to-Jesus moment.”

FULL COVERAGE: Jails under scrutiny

The next few months will be crucial. Baca says he has already taken steps to reduce violence in the jails and defends his record while also resisting calls to discipline his top aides. His spokesman has said the sheriff would not commit to carrying out all of the commission’s suggested reforms until he sees them. They are expected to be released later this month.

Molina said she believes the sheriff is capable of addressing the problems that afflict his jails but must get rid of his top assistant, Undersheriff Paul Tanaka, who was accused by commission investigators of urging deputies to be aggressive and discouraging investigations of misconduct. She said she would call for Baca’s resignation if he does not embrace the commission’s advice.

Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky agreed that Baca must face up to the problems identified earlier this month by the commission’s investigators. “Unlike most other law enforcement executives, he has the capacity to admit mistakes,” Yaroslavsky said. “There are a lot of people in his position who wouldn’t be able to survive this. I think he can.”

Baca, a Republican in a heavily Democratic county, has comfortably won reelection three times, drawing political strength from the same coalition of ethnic groups and other community leaders that helped propel him to victory in his long-shot bid for sheriff in 1998. His current term expires in two years, and the 70-year-old lawman says he plans to run again. But with his management style publicly under fire, there are danger signs for Baca.

A poll last month found that 52% of likely voters disapproved of the sheriff’s job performance, with just 38% approving. But when voters were asked whether they had a favorable view of Baca, the sheriff fared better, with 43% saying they did, compared with 24% who had an unfavorable view. The poll was conducted by district attorney candidate Alan Jackson’s campaign, which asked likely voters about several local politicians, including Baca, who has endorsed Jackson’s opponent.

Raphael Sonenshein, executive director of the Pat Brown Institute of Public Affairs at Cal State L.A., said the poll’s results show that Baca has a reservoir of public support that will help him through his current difficulties but only if he faces up to the real problems and does something to solve them.

“It’s probably not a good time to be ... drawing the wagons in a circle and denying there’s a problem,” he said. “He really needs to turn it around. But at least he has the opportunity.”

Though Baca has said he supports the commission’s work, he was at times defiant while testifying before the panel in July, particularly over whether his senior managers have been held accountable. “You’re not going to tell me how to discipline my people,” he warned the commission’s counsel at one point.

During Tanaka’s testimony at the same hearing, the undersheriff accepted that he could have been more diligent in addressing misconduct by deputies but said his critics have misrepresented his record and unfairly blamed him for problems in the jails.

Dan Schnur, director of USC’s Jesse M. Unruh Institute of Politics, said jail problems don’t typically affect voters’ day-to-day lives and probably wouldn’t sway them to oust Baca unless there were some other significant event, such as a spike in violent crime in the county.

The Sheriff’s Department has faced serious criticism before, but modern L.A. County sheriffs have rarely, if ever, had to deal with the scope of the crisis Baca currently faces.

The jail scandal erupted last year when The Times disclosed that the FBI was secretly investigating allegations of abusive deputies in the lockups. As part of the probe agents paid a corrupt deputy to smuggle a cellphone to an inmate informant. Baca was initially defiant and critical of the federal probe. But allegations of misconduct continued to mount: Jailers were busted for bringing drugs into the jail. Internal memos showed department brass raised alarms about excessive force and deputies inflicting “jailhouse justice” on inmates. Some deputies came forward with tales of beatings and cover-ups.

In October, the Board of Supervisors appointed a commission to investigate the problems and propose reforms. The commission’s investigators presented their findings earlier this month. “This has gone unchecked for so long,” Molina said. “We’re in a very serious crisis in our custody division.”

The department’s troubles recently attracted national attention following disclosures of a secret clique of elite gang deputies, who allegedly sported matching tattoos and celebrated shootings. Last year, the U.S. Department of Justice announced that it was investigating claims by civil rights lawyers that deputies harassed minority residents of government-subsidized housing as part of an effort by local officials to drive out Latino and black residents from historically white Palmdale and Lancaster.

Even before the allegations of jail misconduct surfaced, Baca had been under fire for giving special treatment to friends and supporters, including launching “special” criminal investigations on behalf of two contributors. In July, he was forced to recall an estimated 200 official-looking badges that were given to local politicians and other local officials.

Baca’s role as sheriff -- a countywide elected position -- keeps him more politically insulated than a city police chief. Baca, who declined to comment for this article, can only be voted out by the county’s citizens. Only one incumbent sheriff, Sherman Block, has lost reelection in the last 80 years, and he had died days before the vote. The head of the LAPD, in contrast, can be removed by the City Council or the Police Commission.

Former LAPD Chief Bernard C. Parks, for example, never recovered after a corruption scandal broke out under his watch. Federal authorities negotiated major reforms amid allegations that a unit of anti-gang officers based in the Rampart Division had routinely beaten and framed suspects and covered up unjustified shootings. Parks was replaced in 2002 despite his protests.

The LAPD’s chief also faces more civilian scrutiny - a mayor as a boss and an inspector general and Police Commission that examine problems and demand fixes. The Board of Supervisors controls how much money the Sheriff’s Department is given and how much the county pays out in legal settlements involving deputies but has no other authority over how the sheriff runs his department.

That lack of accountability has historically created a tense dynamic between county supervisors and the sheriff.

In 1991, the board appointed a special counsel to investigate growing concerns about excessive force by deputies. Following an investigation and hearings similar to those conducted this year into Baca’s jails,the resulting “Kolts Report” found “deeply disturbing evidence of excessive force and lax discipline.”

Within days, then-Sheriff Block announced he would seek a fourth term, even though the election was two years away. He ultimately held off opposition from five other candidates and avoided a run-off by winning a majority in the primary.

He served another four years until Baca, who revered Block as a mentor, challenged him.

FULL COVERAGE: Jails under scrutiny

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.