Arts District’s changing landscape is worrisome to longtime residents

Every morning Melissa Richardson Banks walks the Arts District hunting for new scenes. One Saturday it’s the word “Life” stenciled on a sidewalk in black spray paint. A few weeks later it’s a yellow construction crane blocking the skyline.

She has snapped more than 25,000 photographs of her neighborhood in the last year, posting her favorites on her website.

“I’m a little obsessed,” she says proudly. “Something changes every day. It’s like lightning speed.”

In the 1970s, the streets east of Little Tokyo and west of the L.A. River made up a dingy district of hollowed-out warehouses that landlords rented to artists who needed a lot of space for little money. The city passed an artist-in-residence ordinance a few years later that made it legal for them to live in their studios, and it became a bohemian playground — but a rough one. It wasn’t uncommon to see cars with smashed-in windows or someone shooting up drugs in an alley.

Then a decade ago, what started with a new restaurant on this block and then another up that street, turned into an avalanche of development. Warehouses became condos, including a one-time sugar beet storehouse that when converted caught the eye of real estate-savvy actress Diane Keaton. A new coffee shop moves in every month or so, and it’s hard to walk two minutes in any direction in the 52-block neighborhood without finding a blue-and-white filming notice announcing an upcoming car commercial or episode of “New Girl.” And soon, the One Santa Fe complex will be open.

For longtime residents, the changes mean watching their small-community vibe disappear as fast as their once-ample street parking. The most recent census data for the swath of land that includes the Arts District put its population at about 2,700, which means only the people needed to fill the apartments at two of the new development projects will boost the neighborhood’s population roughly 40%.

Although the growth means less crime and more eatery options, some neighborhood veterans say it’s hard to watch their once-left-alone, eclectic haven turn into a trendy and expensive destination that they expect to be priced out of.

“There’s obviously some bittersweet sadness,” Richardson Banks said. “But we also love having a lot of the new restaurants here.”

On a recent afternoon, she met a group of her friends at Eat.Drink.Americano, and the conversation turned to the usual topic among people who lived in the neighborhood years ago: Isn’t it insane how much has changed?

Richardson Banks mentioned her Instagram account as an example. A few years ago only a handful of pictures popped up under #artsdistrict. Now it’s flooded with shots of murals and latte art, and she’s expanded her hashtag repertoire to keep up with her changing neighborhood: #megadevelopment, #construction, #gentrification.

Later, Stephen Seemayer, who is making a documentary about the Arts District’s American Hotel, reminisced about how low the cost of living in the neighborhood was in the late 1970s. During the day, he and his buddies split a 35-cent carafe of coffee at Vickman’s Restaurant & Bakery, and at night they would guzzle cheap beer at Al’s Bar. Both spots have since closed, and long gone are the days when he paid $150 a month for a 3,200-square-foot studio, but those memories make prices at new neighborhood joints hard to believe.

“Four dollars for a cup of coffee?” he says, clutching his stomach in laughter. “It better have crystal meth in it.”

Back in the ‘70s and ‘80s, the neighborhood felt free, he said, almost lawless. People set Christmas trees on fire in the middle of the street, music blared out of Al’s Bar way past 2 a.m. and police cruisers rarely turned down Traction Avenue.

“The cops would say, ‘I’m not getting out of the car. Everything good? Nobody dead? OK, we’re out of here,’” Seemayer recalled. “Now, if a dog craps on an owner’s property....”

He sighed, and instead of finishing his thought about the heightened patrols, he pondered how much longer artists will be able to afford rent in the neighborhood.

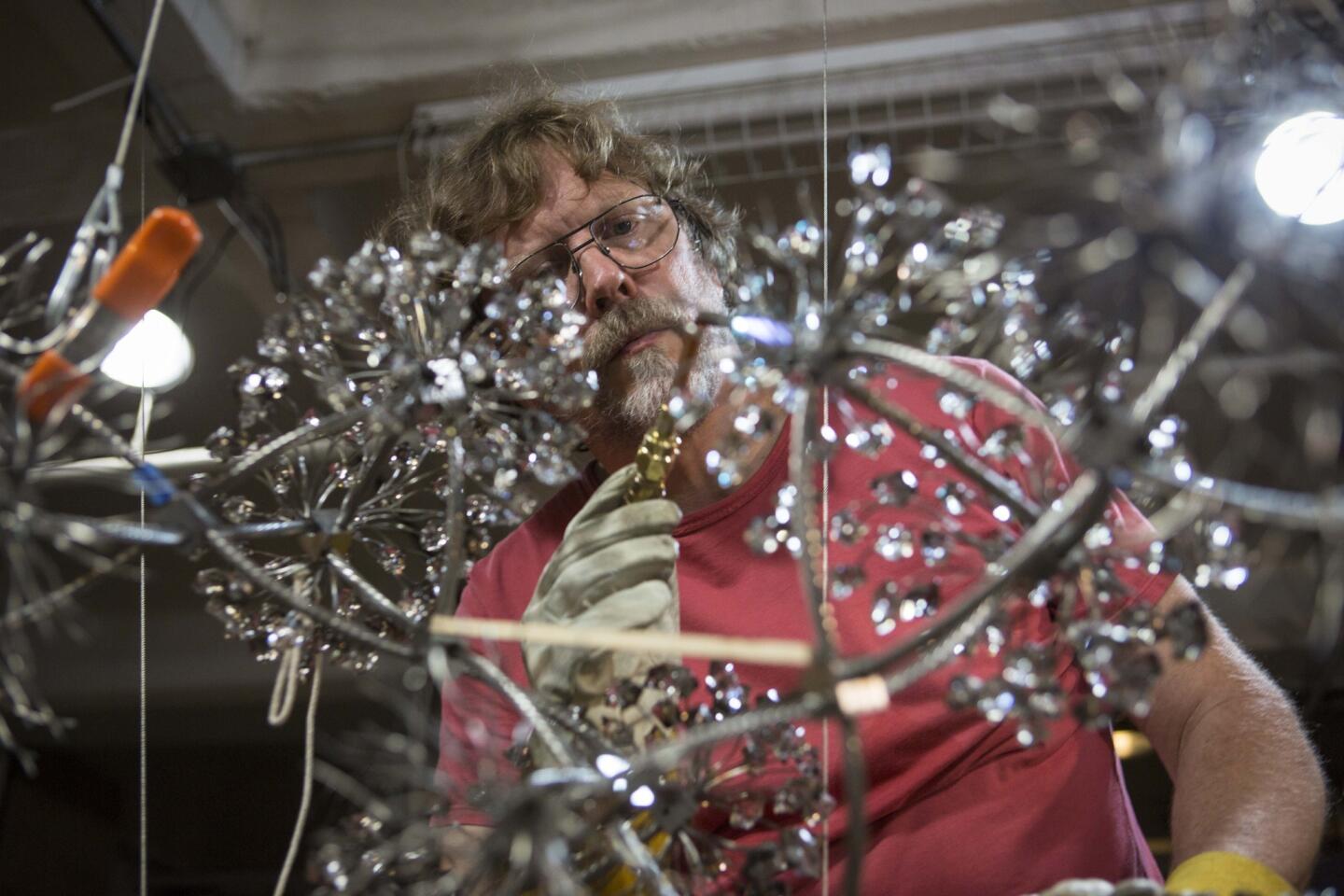

For sculptor Heath Satow, the answer is not long. He pays $3,900 a month for a roughly 5,700-square-foot warehouse at the neighborhood’s edge, but he knows that a gallery up the street pays three times as much. When he gets priced out — and he knows that day is coming — he said he’ll probably move somewhere with lots of cheap warehouse space, like Vernon.

Painter Jett Jackson pays $700 a month for a 275-square-foot loft shaped like a piece of pie. She compared it to living on a boat but said it’s worth it to be surrounded by people who inspire her artistically. She recently returned from a three-year artist-in-residence gig in North Carolina and said she was shocked by the rent increase but encouraged to see that all of the groups she remembers living in the neighborhood — stratolayers, she calls them — are still around: homeless people, off-the-grid types, broke artists who work a second job, medium-income artists and successful ones.

“The geographical layers are intact,” she said. “But the ratios are a little off … and now you have the gentry on top.”

She does worry, though, that as new people keep moving in, they’ll forget about the ones who helped shape the neighborhood.

“Now the plea is, ‘Don’t forget the art and the artist,’” she said.

When she moved back in April, she remembers gawking at a new, boxy building that stretches for a quarter mile or so. Because it’s large and white, she jokingly calls the soon-to-open, $160-million One Santa Fe development the Cruise Ship. (Other residents have their own nicknames: the Wall, the Death Star, the Empire State Building on Its Side.) But city officials and others in the community see One Santa Fe as a linchpin in the effort to revitalize and lure new business to the Arts District.

A few blocks over, in place of the former Megatoys building, a separate apartments-above-retail project by the architectural firm that designed the mixed-use condos at Glendale’s Americana at Brand mall is going up. And in June, a Washington, D.C.-area company announced its plan to team up with the local real estate giant that developed the Third Street Promenade in Santa Monica and invest $61 million in the Arts District.

Dan Lahoda, who lives in the neighborhood and runs the L.A. Freewalls mural project, worries that the development will threaten the neighborhood’s not-like-everywhere-else charm.

“They’re going to have to bring in Starbucks. They’re going to have to bring in the Gap. And J. Crew,” Lahoda said, sighing. “That’s the audience that’s moving in. They’re going to demand it.”

But One Santa Fe developer Bill McGregor of the McGregor Co. said that’s not the case.

Although he wouldn’t go as far as to say no chain stores will move in, he emphasized that they would be the minority. As for concerns about parking, he said the project includes an underground, 800-car lot.

“We have very much sought to design a project … that is architecturally and planning-wise compatible with the character of the Arts District,” he said.

For longtimers, it’s hard not to view these changes through the context of past ones.

They think about what it felt like to lose Al’s Bar in 2001. When the dive that once hosted bands such as Nirvana and the Misfits closed, Jackson lost the bar beneath her old apartment. Richardson Banks lost her “neighborhood church.” And Seemayer lost the place he met his wife, the bartender, in 1981. Now it’s a yoga studio, and they joke about people doing downward dog on a floor that has seen so much vomit.

Seemayer remembers sitting at the bar in the late ‘70s, soon after The Times, the Herald Examiner and Sunset magazine published pieces about the neighborhood. He noticed unfamiliar faces and sighed in disgust at the arrival of uppity newcomers.

“This place has gone to hell,” he recalled saying. “I just remember sitting there and being disdainful. All of 24 years old and going, ‘Oh, it’s over now.’”

Now he laughs at the melodrama and finds it’s strangely comforting to remember how certain he felt back then that the neighborhood was ruined and how glad he is now that he was wrong.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.