After all these years, potter Otto Heino is still going strong. Just peek in his home and studio.

The first in a yearlong series profiling California’s living legends of midcentury design.

AT 94, Otto Heino has no time for false modesty.

“I am,” he says, “the oldest, richest potter in the world.”

With an output of 10,000 pieces a year, Heino might also add “most prolific” to his list of superlatives. For more than six decades, the Ojai artist has been the workhorse of post-World War II ceramics, one of the artisans who transformed California crafts into a national design movement in the 1950s to ‘70s. Now that home furnishings are falling in step with a burgeoning green movement, Heino’s work is resonating with a new generation drawn to his earthy, organic expression of midcentury modernism.

“He has understood and manipulated clay as well as -- or better than -- the handful of ceramists whose work transcends crafts,” says Los Angeles Modern Auctions owner Peter Loughrey, who has seen prices for Heino pieces double in the last few years. “And his experiments with glazing and firing techniques -- well, it practically takes a scientist to do what he has done.”

Indeed, Heino and his late wife, Vivika, spent about 15 years developing the formula for a once-lost ancient Asian glaze that produces a velvety, low-sheen yellow on high-temperature stoneware and porcelain. Despite million-dollar-plus offers from companies in China, Japan and Korea, the recipe remains his secret. Instead, he sells his own pottery with the signature finish for as much as $25,000 per piece.

Among collectors, Heino also is known for jade-like celadon, rich blues and turquoises, pale purples and blood reds.

“The surface and color and the iron spots on a lot of the pots make them look natural, unmanipulated, like a rock you’d find somewhere,” Doug Van Sickle, a Sherman Oaks potter who studied with Heino, says of the finishes -- some glassy, some satiny, others rough and speckled. “To get that look, you have to make your own clay.”

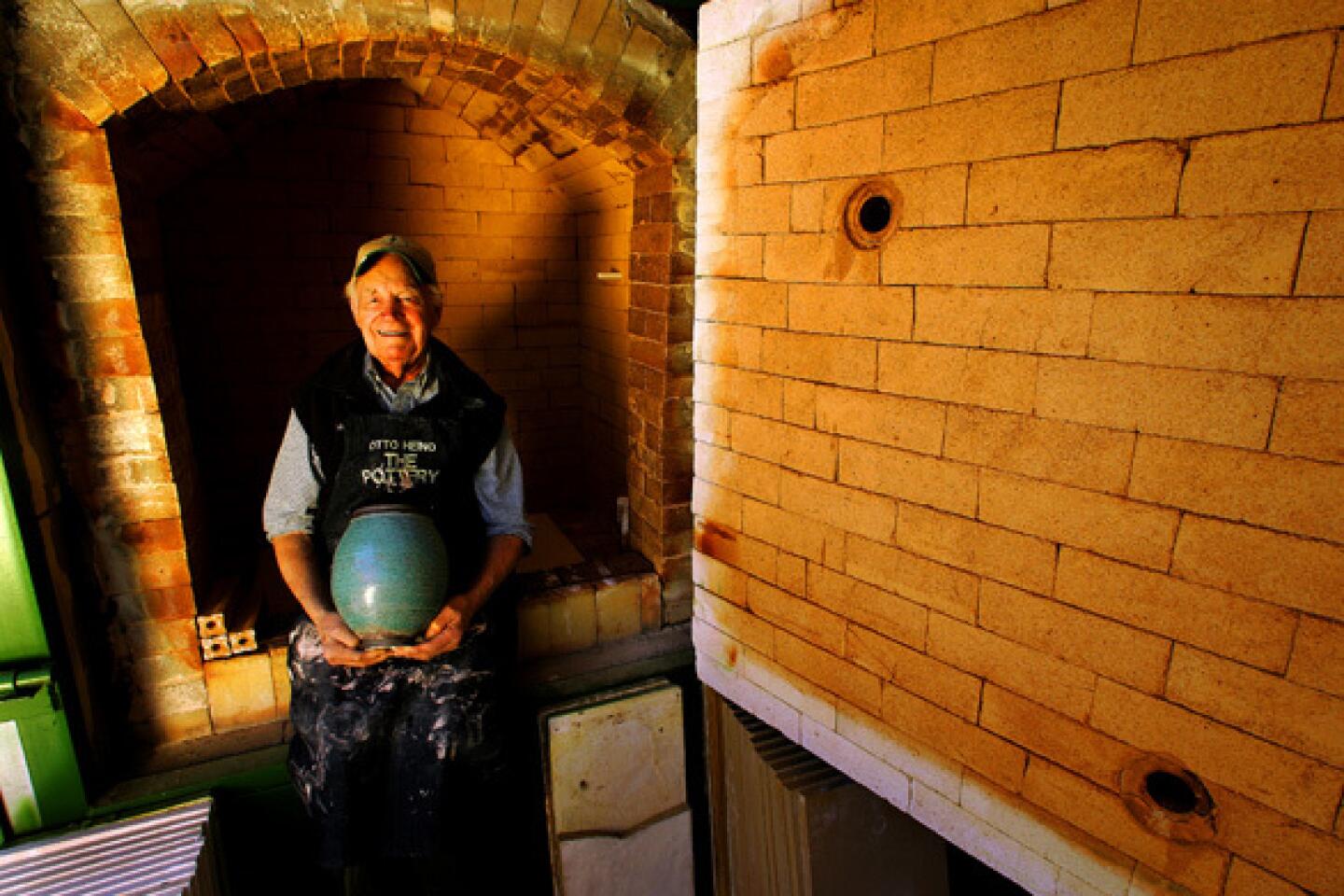

Despite his age and slight physique, Heino still fires his own pottery at 2,575 degrees inside the nine kilns of his cinder-block home studio. He packs and ships overseas orders himself and sells $150-and-up pieces to visitors in a showroom that the architect Lloyd Wright designed for the property’s original owner, the esteemed potter Beatrice Wood.

And, of course, he still throws at his wheel. During a recent visit to his studio, Heino effortlessly turned 50 pounds of clay into five impressive bowls and vases in well under an hour.

ALONG with Vivika, who taught generations of potters before her passing in 1995, Heino embodied the spirit of the 1950s studio crafts movement. In Southern California, modern ceramists such as the Heinos and Otto and Gertrud Natzler ushered in a new era -- “a merger of designer and craftsman, and a unification of form and function,” says Christy Johnson, director of the American Museum of Ceramic Art in Pomona.

In workshops often set up in pastoral communities such as Ojai, these artisans sharpened their skills while earning a living. Demand for their work was driven by the postwar boom for tract-style homes, Johnson says. “The style was modern -- lots of glass, open floor plans -- and that architecture called for a different type of decorative art.”

Otto and Vivika produced fittingly modern objects that were appreciated for their natural materials. In the back-to-the-earth counterculture of the 1960s, Johnson notes, such studio pottery fit the social and political priorities of the time.

Among artists, the couple were known for being generous with their expertise.

“They were the teachers who taught the teachers who taught us all,” says Van Sickle, 54, who studied with the Heinos in the 1980s. “To this day, I mix my own clay and glazes, just like they did.”

This organic style -- something Heino calls “rugged but delicate” -- is informed by centuries of craftsmanship. Bulbous vases with narrow necks and other simple, elegant shapes recall traditional Japanese pottery. His nature-inspired decorations reflect the English Arts and Crafts movement of the early 20th century as well as the indoor-outdoor lifestyle of Southern California.

But most important, Heino’s work ethic and aesthetic are in line with the Bauhaus philosophy of functional design.

It is a modernist sensibility that continues to influence contemporary California artists of note, including Van Sickle, Adam Silverman of Atwater Pottery in Los Angeles, Kevin Nguyen of Xiem Clay Center in Pasadena and James Haggerty, a Santa Barbara ceramist who at 13 was Vivika Heino’s youngest student.

“For those of us who work in creating vessels, as opposed to sculptural ceramics, Otto’s work is a perfect unity of throwing technique and refined forms,” Haggerty says, “a great example of what clay and glaze can do together.”

OTTO HEINO was born Aho Heino, a second generation Finnish-American in East Hampton, Conn., who with 11 siblings weathered the Great Depression raising dairy cows and delivering milk.

In World War II, while serving as a waist gunner aboard a B-17 bomber, Heino says he was shot down twice over Germany and escaped death because of his blond hair, blue eyes and dog tags with the more Teutonic-sounding “Otto Heino.”

During five years of Air Force duty, he briefly worked on engines at a Rolls-Royce factory in England. There he visited the studio of the legendary Bernard Leach, the Hong Kong-born artist who introduced Japanese techniques to British pottery, and the decision was made: “That was what I wanted to do,” Heino recalls.

At the end of the war, he attended the League of New Hampshire Arts and Crafts, where he studied painting and ceramics. He married his pottery instructor, Vivika, who in 1952 was recruited to teach at the University of Southern California.

Heino’s mechanical abilities and knowledge of ceramics led to a job with NASA here crafting nose cones for rockets. Well compensated but artistically unfulfilled, he gave up the position after 13 years to became a full-time potter.

The couple bought Wood’s home in the early 1970s (“paid her $35,000 cash,” Heino recalls) and set up shop in Ojai, signing their works “Vivika and Otto.”

Ask about his process today, and Heino simply responds, “The clay shows me what to do.” He centers the material on his wheel, squeezes it into a cylinder, then presses his thumbs down the center and out to the edges, drawing the clay upward with his fingers to create the walls of a bowl.

After 60 years, it’s an entirely intuitive set of movements. Unlike most potters, Heino uses little water to shape his creations. By not thinning out the clay, he can make sturdy vessels that are more than 2 feet tall or wide.

“You tend to see the same shapes again and again in Otto’s work,” says Gerard O’Brien, owner of Reform, a Los Angeles gallery specializing in California design and decorative arts. “He developed his vocabulary of utilitarian forms early on and added natural elements like leaves and branches impressed into the clay, and colored slip [liquid clay] painted with calligraphy brushes.”

The glazes, however, are Heino’s greatest legacy.

His famous yellow formula sells for $75,000 per 5-gallon bucket, Van Sickle says, “which I doubt costs more than $5 to make.”

When Heino first began selling the yellow pottery overseas, he received six-figure checks and wire transfers that led federal agents to his studio.

“They thought I was selling drugs,” Heino says with a laugh, recalling notations on the payments that said, “for pot.”

TODAY, where pet peacocks once strolled, the lush grounds of the artist’s home are patrolled by the border collie Robbie II.

In the kitchen, a collection of copper pots and pans -- wedding gifts to Otto and Vivika -- still hang from a shelf that he designed, and Heino still eats from stoneware plates made in the studio a quarter-century ago.

They’re decorated with his late wife’s calligraphic rendering of a blue swallow, a design that also appears on the master bath’s tiles -- fitting for the man who won the gold medal at the 1978 Biennale Internationale de Ceramique d’Art in Vallauris, France, for a pot decorated with tiny birds perched on the rim.

A long teak dining table and chairs designed by Danish architect Hans Wegner stretch through the kitchen, leading the eye to an original wrought-iron butterfly chair with leather seat and a gas-powered potbellied stove that sits by a wall covered in handmade Heino tiles.

On the other side of the stove, a Windsor-style chair is testament to Heino’s East Coast roots.

“I like American Colonial and the old New England stuff,” says Heino, who sleeps in an old four-poster bed and hangs wooden pitchforks and cookie molds as art.

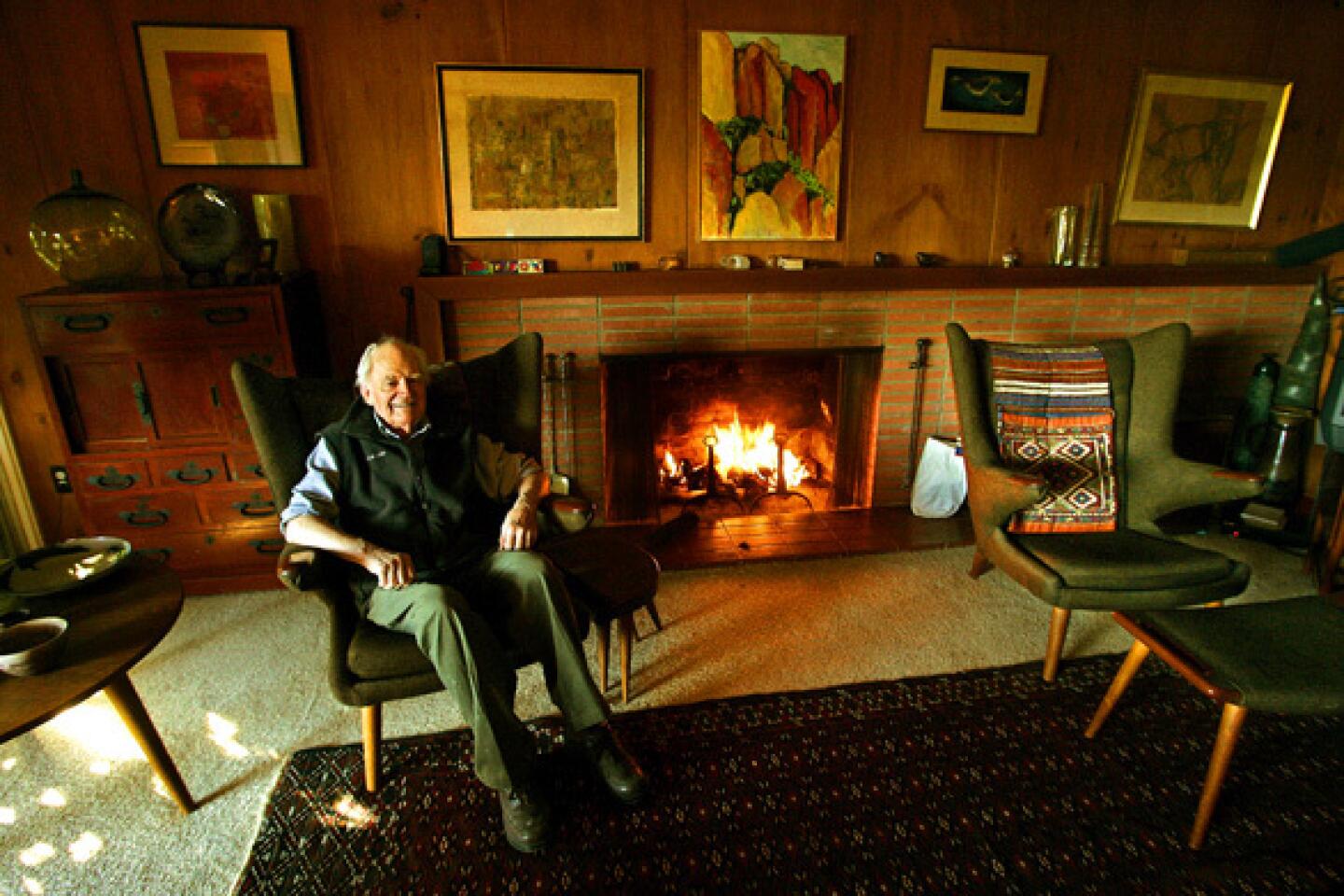

The living room is a midcentury modernist collector’s dream: A pair of authentic Papa Bears, Wegner’s jet-age version of a wing chair, straddle a flagstone fireplace.

Danish credenzas and tables are covered in ‘50s and ‘60s ceramic lamps and bric-a-brac. A long, lean Wegner sofa serves as a backdrop for ethnic and folkloric pillows and textiles. It is in this room that Heino lights a fire in winter or watches the Lakers on TV.

In February, doctors installed a pacemaker that slowed Heino down for a couple of weeks. But he was back to work soon enough.

“Never hurry, never worry,” he says, describing his attitude toward art and life.

“If you’re negative, you’ll never make it.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.