Great Read: In Alabama same-sex marriage battle, county judges caught in the middle

Reporting from Point Clear, Ala. — About 9 o’clock the night of Feb. 8, Judge Tim Russell felt his phone vibrate, which seemed strange at that hour. It was his work phone.

He and his wife, Sandy, had just finished the long drive from Birmingham, Ala., where they visited family, back home to Baldwin County, on the Gulf of Mexico. While she readied for bed, he stood reading an email from Roy Moore, the chief justice of Alabama’s Supreme Court.

In less than 12 hours, Russell and other county judges were to start granting marriage licenses to all couples, whether gay or straight.

Russell finished reading the message and held it out to his wife.

“My God,” he said.

::

Russell lives with one foot in the past and one in the present, and talks as easily about either.

Driving to lunch recently, he casually recalled his maternal grandmother of 13 generations ago, Rebecca Nurse. She was hanged in 1692 for practicing witchcraft, and became a central character in Arthur Miller’s play “The Crucible.”

The modern relevance of that story isn’t lost on Russell. “I think a great deal about our freedoms,” he said.

Religious freedoms, he said. And also equality under the law.

Among all the states, Alabama is the most staunchly opposed to same-sex marriage, survey after survey shows. So it serves as a watershed, a ridge beyond which nationwide acceptance seems inevitable.

There was little surprise, then, when a legal skirmish erupted between Alabama’s top judge, Moore, and his nemesis, the United States government.

It’s only the latest battle in a war between state and union that has gone on for a century and a half, in various incarnations. This time, though, there are subtleties happening beneath the flashy rhetoric from top officials. There are changes afoot in Alabama, in which smaller legal players stand at odds with, and even undermine, their leaders.

Players like Probate Judge Russell.

As he curved south along the bluffs over Mobile Bay, the 66-year-old judge talked about Confederate soldiers dumping barrels of turpentine into the water so that Northern troops couldn’t use it, and pointed to the site where his great-uncle and namesake was shot to death by an unknown assailant in 1919.

He stopped for lunch at the Grand Hotel, an antebellum fixture in Point Clear that overlooks the bay. Enormous live oaks groaned in the wind, with branches so old and heavy that they grow into the soil and then reemerge.

Each afternoon a snare drummer leads a procession to the waterfront, where the hotel staff fires a brass cannon over the bay. It’s a nod to wars of the past, a gallant and antiquated gesture, and Russell feels at ease in the old hotel’s atmosphere.

He wears a suit, and never removes his jacket. His sweep of perfect white hair gives him an air of wisdom before he ever speaks. When he does, his accent is local to Baldwin County itself, and old enough that the edges long ago wore away from his consonants.

Settling into a chair in the dining room with a view of the oaks, he embodies a certain Southernness. He personifies a state that seems at first glance to be stuck in a long-gone time. But within him, like Alabama itself, there is more complexity than first appears.

::

“I was all set to begin issuing licenses, same-sex or otherwise,” Russell said.

A U.S. District Court judge had handed down an order for county-level probate judges throughout the state to issue licenses to anyone who qualified, regardless of gender or orientation, beginning Feb. 9.

Then at the last moment Moore weighed in with his contradictory opinion, by email: “No probate judge shall issue or recognize a marriage license that is inconsistent with Article 1, Section 36.03, of the Alabama Constitution or ... 30-1-19, Ala. Code 1975.”

No probate judge shall.

Shall.

The rest of the citation was legal ornamentation. The word “shall” made it an order, and deftly recalled the source of Moore’s fame and power: standing up to the federal government in 2003, over the display of the Ten Commandments in his courthouse. Thou shall, and shall not.

A special judicial court had removed Moore from his position after that showdown, but the people of Alabama immediately elected him back into it.

His email the night before the advent of same-sex marriages placed the state’s probate judges in a double bind. They started buzzing like students in a middle school cafeteria.

“Probate judges all started emailing and calling each other,” Russell said. “‘What are you going to do?’ ... ‘Well, what are YOU going to do?’”

Russell felt pulled in two directions: He feared that he would run afoul of the Alabama Constitution if he issued licenses to gay couples. And he worried he’d break the U.S. Constitution if he didn’t.

So he decided to split the difference. At 8 a.m. Feb. 9, he began accepting applications for licenses, regardless of who applied. But he didn’t actually issue licenses to gay couples — he just kept the applications on hand.

Moore’s opponents felt sympathy for the probate judges.

“I think most of them are genuinely trying their best,” said Heather Fann, a Birmingham-based attorney hired by the National Center for Lesbian Rights to fight Moore’s order. “I think most of them are trying to sort this out as a matter of states’ rights.”

The first bind the judges faced, and arguably the easier to solve, was merely legal. Whose order should they follow?

The second, more intractable bind threatened their livelihoods. Probate judges are elected, not appointed. Did they dare contradict Moore, and perhaps the electorate?

::

There is a hierarchy of authority among judges. But at the lowest levels of federal power, and the highest levels of state power, they overlap.

That’s exactly where this case landed.

“We all know that the Supreme Court of the United States is the final court. Nobody would argue that,” Russell said. “But the states’ rights people would argue that the Supreme Court of Alabama, on any state constitutional issue, can only be overruled by either the appellate court in Atlanta or the U.S. Supreme Court. That a single federal judge over a part of the state has no authority over the Alabama Constitution. That’s the issue. That’s what’s causing the problem.”

All of this frightened the probate judges. Russell, in the day of chaos following Moore’s order, began interviews by saying, “On the advice of my counsel, my outside counsel ...”

It seemed bizarre, the notion of a judge — a sorter and divider of the law — to need a lawyer of his own. But in Alabama, it turns out, probate judges don’t need to be attorneys. Of the 68 of them, only 12 are lawyers. As Russell put it, “I have to speak from my heart, instead of from legal training.”

Moore was content, or even eager, to martyr himself as a judge because he has his eye on higher elected positions. He did not return calls for comment.

Russell’s openness on this point reveals just how little faith the lower judges have in Moore’s motivation: “Oh yeah,” he said. “He’s looking for either a governorship or senatorship.”

That may seem nonsensical at first; how would picking a losing battle help boost Moore to a higher position? Understanding it requires a moment of thought about a character trait of the South in general, and of Alabama in particular.

No one discusses the Civil War here, in normal conversation, or even thinks consciously about it. It’s relegated to history classes and hobbyists. But the South’s loss still echoes; there is a vestigial rebellion that children learn even before they ever study the Civil War in school.

Alabama’s state motto sounds majestic in Latin. “Audemus Jura Nostra Defendere.”

In English it’s more pugnacious: “We Dare Defend Our Rights.”

::

Russell and all the other probate judges found themselves stuck.

“This has kept me awake at night,” he said. “I won’t suffer because of this. The state of Alabama won’t suffer. But the couples. They may be hurt in the end.”

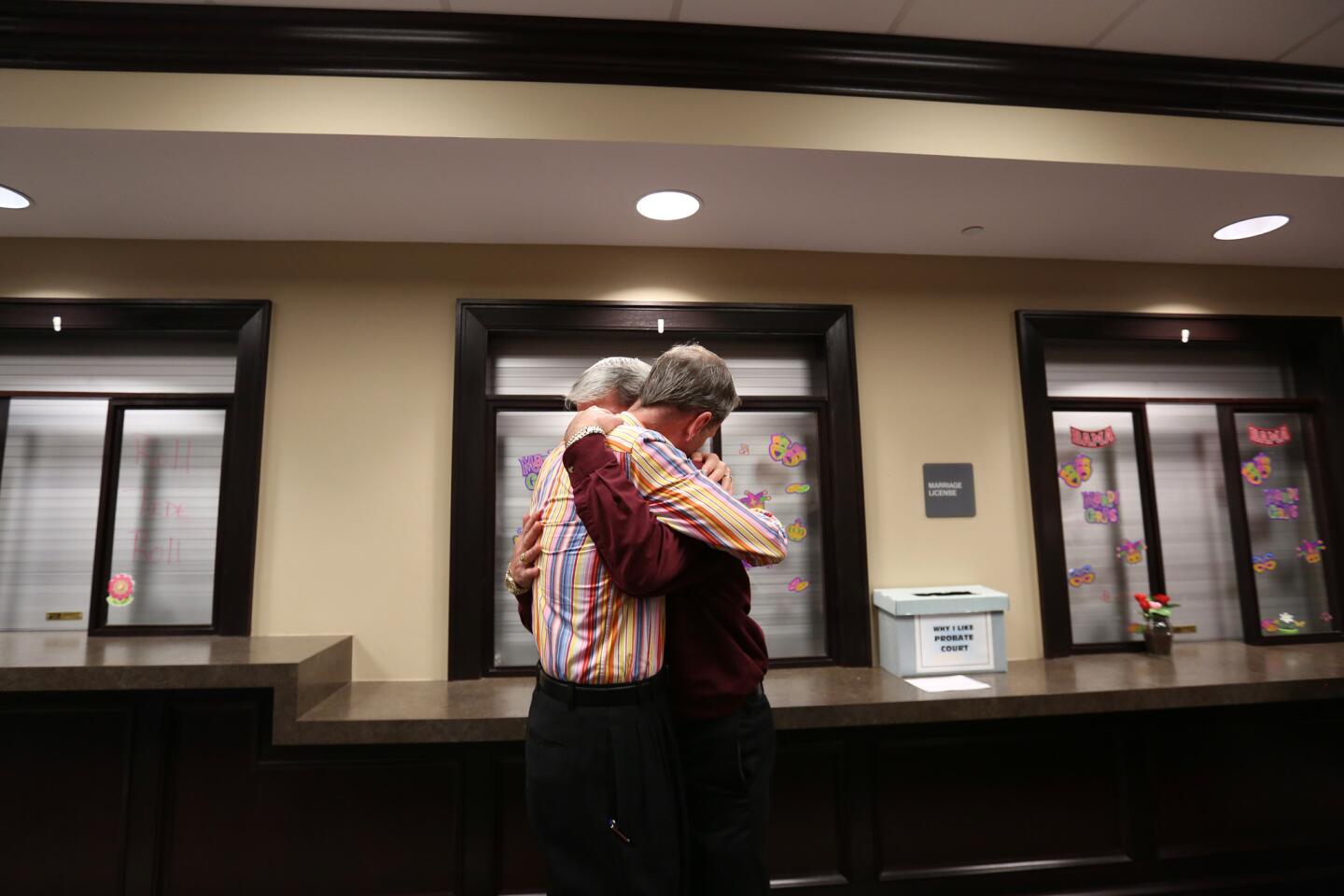

In mid-February, U.S. District Judge Callie Granade contradicted Moore, clarifying that same-sex couples should receive licenses. So Russell moved ahead, issuing them immediately.

Just as he feared, on March 3 the Alabama Supreme Court weighed in with an opinion against same-sex marriage, effectively making it illegal for probate judges to issue such licenses.

So Russell retreated to his one-man split decision:

“Based on the advice of legal counsel,” he wrote in a statement, “Baldwin County Probate will continue issuing marriage licenses, but will hold applications for same-sex marriages until further guidance is given by legal counsel and the courts.”

The issue will ultimately be decided this spring, when the U.S. Supreme Court takes up the case.

Beyond those decisions, though — beyond legalities — there’s also the question of his Catholicism, Russell said. Previously religion guided his thinking on marriage: It’s between one man and one woman, he believed.

But the current debate has forced Russell to do to himself what he does to couples and estates and other subjects every day: He is dividing his own mind. Separating the biblical and the constitutional. Cleaving the opinions he holds in his church pew from the ones he issues from his courthouse bench.

Is it possible to separate the two entities completely? One sort of union for the church and another for the state. One for religion and one for the law. Would he support that?

Russell sat a moment, gazing at his lunch. Then he looked up with a snap.

“I would have no problem with that,” he said. “I would support that.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.