Great Read: Learning to love ‘lucha’ in an L.A. ‘Aztec Temple’

Fidel Bravo was minding his own business, eyes locked on the fight happening 5 feet away, when a massive shadow spilled over him.

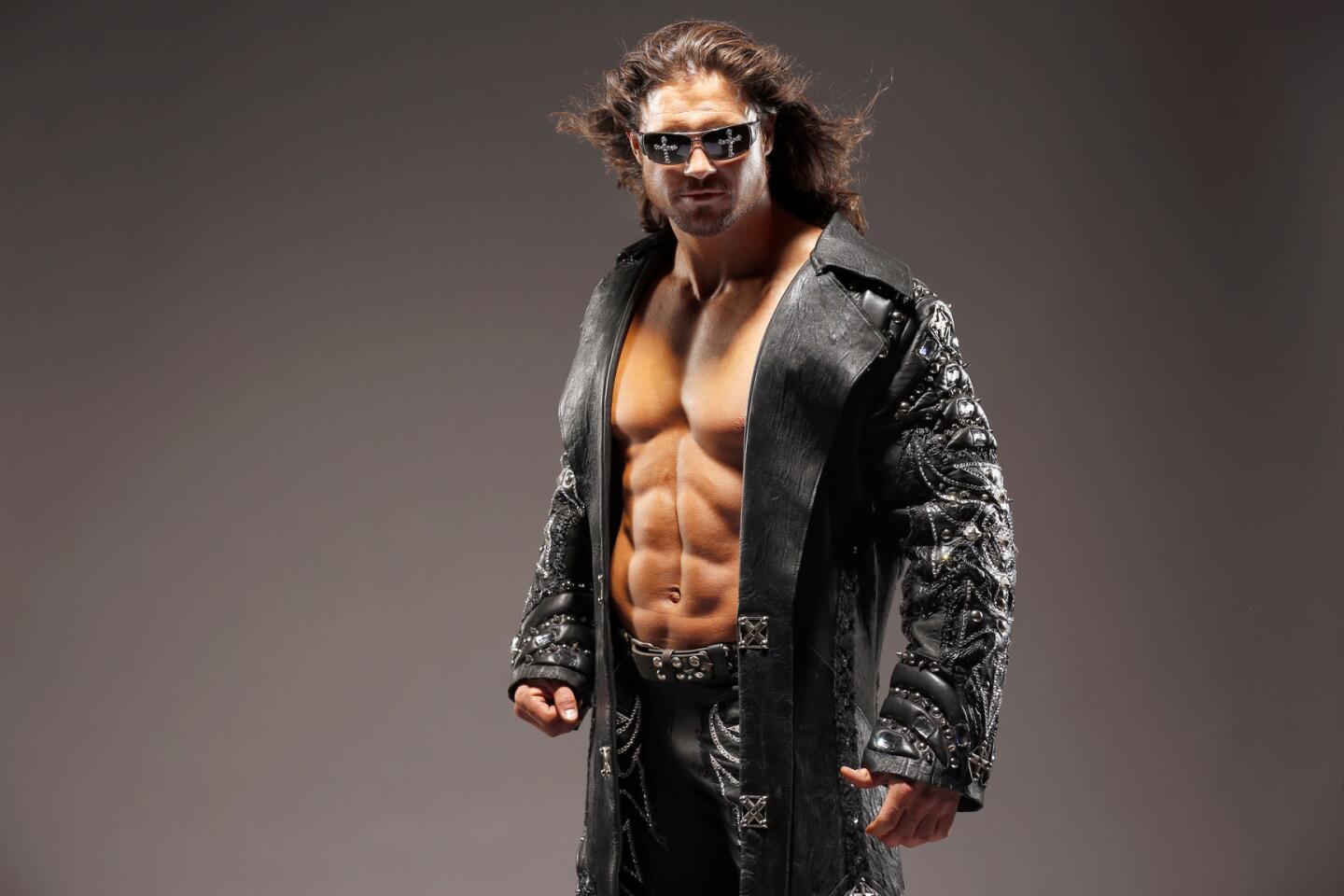

Bravo, a lanky 22-year-old who doesn’t look much for fisticuffs, had something the man casting the shadow wanted. All muscle, tattoos and sneer, the man placed his hands around Bravo’s collar and plucked him out of his seat. Keeping Bravo airborne with one hand, the man-mountain yanked his belt off with the other.

Then Hernandez, a Texas-born strongman who made a name for himself by pummeling opponents in Florida, Mexico and Los Angeles, dropped Bravo back in his seat and headed back to the ring with the belt, intent on using it to bloody his next victim.

“I was terrified. I thought he was going to kill me,” Bravo said about an hour later, eyes still wide.

Then a smile flashed across his face.

“It was awesome,” he said.

Welcome to Lucha Underground, the Boyle Heights wrestling promotion where the line between fan and fighter is crossed as easily as the ring ropes.

The company is hoping to revive interest in the lucha libre style of wrestling, a staple of Mexican culture that has often struggled to gain national prominence in the U.S. The group also wants to strengthen cultural pride among Boyle Heights’ Mexican American residents, placing its “Aztec temple” where its luchadores take flight in a warehouse district just off the Los Angeles River.

“Right now, the Latino population is growing so much in this city, in Los Angeles, it is very important for lucha libre to be in this part of America,” said Dorian Roldan, a co-owner of Lucha Underground, whose uncle founded Asistencia Asesoria y Administracion, the largest lucha libre outfit in Mexico. “There was no doubt that Los Angeles, more specifically this neighborhood, was the perfect place to start.”

Most of Lucha Underground’s boisterous crowd lives within walking distance of the temple. On a Sunday in April, two of the show’s producers walked through the ringside area and pointed out fans by name. There was Ruben Rangel, the local tattoo artist who has designed masks for two of Lucha Underground’s most popular combatants. Nearby was Victor Gonzalez, the dreadlocked super-fan who leads chants in the temple and has attended all but two of the company’s nearly three dozen events.

As Gonzalez discussed his love of lucha, a staff member walked up, shook his hand and talked about a possible hangout later that night.

“You’re practically crew at this point,” the man said.

::

Local promoters have run smaller lucha libre shows throughout Southern California for years, but it’s been a long time since a lucha-driven promotion has reached an audience of this size through a national television broadcast. Although the temple seats just 300, the El Rey network can beam Lucha Underground episodes into 40 million homes across the U.S.

The style has always been popular throughout the border states, and Mexican promotions such as Asistencia Asesoria y Administracion and Consejo Mundial de Lucha Libre routinely sold out the Los Angeles Sports Arena in the 1990s.

“When they would come to town they were drawing really big crowds,” said Dave Meltzer, publisher of the Wrestling Observer Newsletter. “Out of 17,000 fans, I would say there would be less than 50 that weren’t Mexicans.”

American interest has waned since. Mexican stars have occasionally gained prominence in the ubiquitous World Wrestling Entertainment, but the lucha style — which features smaller, acrobatic competitors who use backflips and spin kicks where their American counterparts might simply throw a punch — has always been something of a sideshow there, rarely the main attraction.

Lucha Underground is working to change that perception. Combining a gritty cinematic crime film setting with the traditional superhero feel of lucha libre, the promotion has gained national attention through El Rey, which is broadcasting 39 episodes that will air through the summer. Television deals are the lifeblood of pro wrestling, the dividing line between lesser-known promotions and elite ones.

A quick tour of Lucha Underground’s temple reveals a setting devoid of the glitz often associated with World Wrestling Entertainment. Fans aren’t paying $125 to sit ringside at Staples Center. The top stars don’t have their own dressing rooms.

The company’s Boyle Heights headquarters is a vacant warehouse. Massive smelting vats and cranes sit just outside the camera’s lens. Wide-open doors and roaring industrial fans are used to keep the building cool, but the stink of sweat pervades the space. The locker room walls are a mosaic, each a turf battle between Mesoamerican imagery and graffiti tags scrawled by local artists.

That gritty look comes from the influence of grindhouse maestro Robert Rodriguez, who owns El Rey and helped launch Lucha Underground.

“We wanted the set to be a reflection of lucha’s heritage, and we are proud to support and inspire up-and-coming creatives as they endeavor to break into this business,” the filmmaker said by email. “So asking them to participate in the creation of the set and costumes was an organic extension of who we are.”

Executive Producer John Fogelman said he didn’t want the set to resemble a wrestling arena. The temple, he said, is a place where men come to settle disputes.

“We wanted it to look like ‘Fight Club,’ ” he said.

::

The differences between Lucha Underground and traditional lucha libre fights are clear inside the ring as well. Many of its gladiators don’t wear masks, and while the dizzying, full-throttle lucha style dominates the in-ring action, plenty of Lucha Underground’s grapplers work at a slower, brawling pace.

Jose Alberto Rodriguez, who does battle as Alberto El Patron, said they are trying to appeal to a broader audience and present a slice of Mexican culture to a wider ethnic demographic.

“In the past, there was just one spot or two spots for Latino wrestlers ... but here it’s all about the Latin culture. They’re so interested in showing, not just to Mexican Americans but to everybody here in the U.S., what the Latin culture is,” said Rodriguez, a tall, lithe figure with a mixed martial artist’s build.

“That’s the reason this show is not just a wrestling show. You can really learn something from this show, because we talk about the Mayan culture, the Aztec culture.”

The company has helped extend the careers of wrestlers, Latino and otherwise, who want to purvey the lucha style in the U.S. but either fell out of favor with World Wrestling Entertainment or could never break into the company.

Rodriguez, who is the nephew of legendary luchadore Mil Mascaras and once wrestled under a mask in Mexico as Dos Caras Jr., is a former World Wrestling Entertainment champion who left the company under acrimonious circumstances. Lucha Underground stars such as Chavo Guerrero Jr., who is also descended from Mexican wrestling royalty, and John Hennigan also left World Wrestling Entertainment and found themselves bouncing around on the independent circuit before arriving in Boyle Heights.

The temple has also become a stage for Mexican grapplers who previously had no exposure in the U.S., such as the enigmatic Sexy Star, who subscribes to Mexican tradition and keeps her identity private. Unlike other U.S. promotions, where women and men rarely interact, Sexy Star frequently faces off with her male counterparts, flying around the ring wearing a black Lycra mask.

“I am very proud to be doing this, but it is also tied to being a woman, that culture of being a fighter,” she said through an interpreter. “The lucha libre culture allows for women to become warriors, and that is something that I really celebrate and value bringing to the U.S.”

::

Back in the ring, Sexy Star stared down a male opponent twice her size. Her cocksure enemy, Marty “The Moth” Martinez, strutted around the squared circle, confident that he was about to pound her into the canvas.

The bell rang and The Moth began to manhandle Sexy Star. Minutes passed, and the crowd of 300 packed into the temple began jeering Martinez in Spanish, then cursing him in English. Sexy Star broke free of a submission hold, and the mob tried to rally her.

Desperate for an opening, she picked up the pace. The big man ran face-first into a dropkick. Then another. Sexy Star trapped him in her powerful thighs and flipped him over.

With the crowd behind her, Sexy Star climbed to the top rope and crashed down on Martinez. The referee slid into position and counted. One. Two. Three. The crowd erupted with delight.

Sitting at ringside, tattoo artist Rangel was among Sexy Star’s most boisterous supporters. She was wearing a mask of his design, after all, and his own face was hidden behind a Lycra mask he had recently made.

This was the kind of entertainment Boyle Heights’ Mexican American residents — and Lucha Underground’s no-collar crowd — want, Rangel said.

“It’s very important to have this,” he said. “This is the opera for the poor.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.