See how LAUSD has wavered between picking leaders from the outside and within

Michelle King is the first African American woman to lead L.A. Unified.

One of the most salient headlines about the hiring of Michelle King as the superintendent of the Los Angeles Unified School District is that she’s an insider -- a district stalwart who worked her way up the LAUSD ladder over a span of 30 years -- and not someone with a glitzy national name, such as a vice admiral in the Navy or a former governor.

The history of L.A. Unified’s leadership provides context to King’s appointment: The district is constantly revising its view on whether it needs an insider to stabilize the schools, or an outsider to shake them up. And history hasn’t settled the question of whether being an insider is a help, or a hindrance.

Over 45 years, the margin of insiders to outsiders leading the district was eight to five. Here is a timeline of the superintendents in recent history, how the board chose them, and how they fared:

1971-1981

William J. Johnston - INSIDER

Supt. William J. Johnston, 1971-1981

Supt. William J. Johnston, 1971-1981 (L.A. Times file photo)

Johnston was promoted from within the ranks of L.A. Unified. Before his appointment, he served as assistant superintendent for adult education, the focus of his graduate education. Observers saw his “young, energetic” personality as an asset to promoting renewal within the schools. He started in L.A. Unified as a math teacher and junior varsity baseball coach at Gardena High School.

His insider ties extended beyond his own LAUSD career. His dad, Ogden “Johnny” Johnston, had been warmly remembered as a wood shop teacher for nearly 40 years at Roosevelt High in East Los Angeles.

During his tenure as superintendent, he established the All-District Honors Band. As superintendent, Johnston also encouraged LAUSD schools to participate in what was then the new state academic decathlon competition.

Johnston still corresponds, by formal letter, with district leaders, offering his opinions and guidance.

1981-1987

Harry Handler - INSIDER

Harry Handler was superintendent from 1981-1987

Harry Handler was superintendent from 1981-1987 (L.A. Times file photo)

Handler had been serving as Johnston’s chief deputy when he was appointed superintendent. He joined LAUSD in 1952 as a substitute junior high math teacher, and later served as supervisor of guidance and counseling for junior and senior high schools. In 1968, Handler was named to the district's newly created post of director of research and development. He later became associate superintendent for instruction.

As The Times reported upon his appointment, “His selection is expected to please top district officials, who wanted to see the practice of promoting from within the ranks continued.”

Discord over desegregation was still brewing when he took office. The board Handler inherited was polarized, consumed with bitter busing fights and the aftermath of white flight by students and teachers. However, “Handler's most enduring legacy,” The Times wrote in an editorial the day he left office, “may be a school board that works in harmony.”

1987-1990

Leonard M. Britton - OUTSIDER

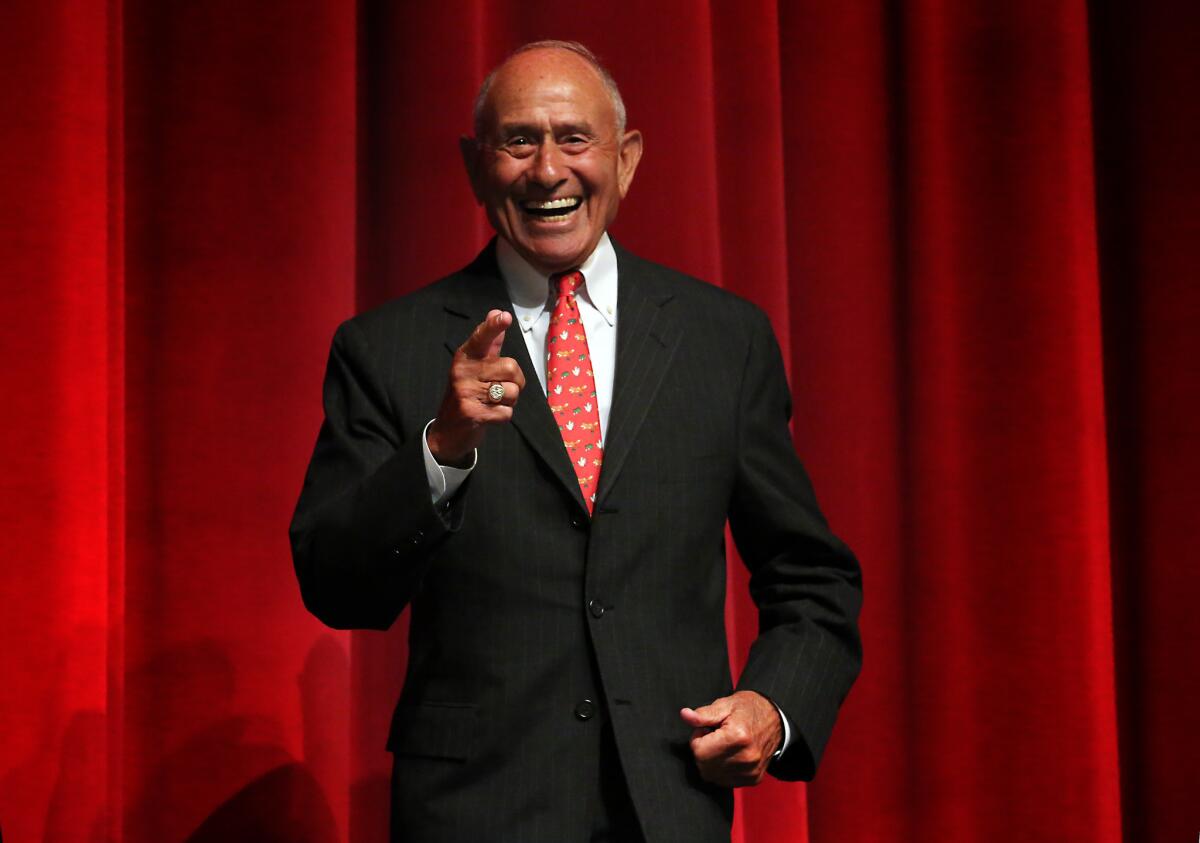

Leonard Britton, superintendent of LAUSD from 1987 to 1990.

Leonard Britton, superintendent of LAUSD from 1987 to 1990. (L.A. Times file photo)

Britton had the distinction of being the first outsider appointed as LAUSD superintendent in nearly 40 years. He uprooted himself from a successful legacy as head of the Miami-Dade County public schools. In his seven years in Miami, Britton developed well-regarded specialty schools, including one for pregnant teens. He strengthened relations with the teachers union, developed a group of effective administrators and experimented with school-based management. It was that reputation and record that prompted his appointment in Los Angeles.

However, the complex political landscape of LAUSD was riddled with tough issues, making for a steep learning curve. He faced a combative teachers union and a fragmented board against the backdrop of an economic downturn. He was unable to translate his success in Miami to Los Angeles before he resigned in 1990. "We never found out what Leonard Britton could do for L.A. Unified because he never got a chance," former school board member Jackie Goldberg said. "He had a lot to offer."

Eventually, the board voted to buy out Britton's contract.

1990-1992

William R. Antón - INSIDER

William Anton, LAUSD superintendent from 1990-1992.

William Anton, LAUSD superintendent from 1990-1992. (L.A. Times file photo)

As a result of Britton’s perceived failure, the board abruptly ditched its ideas for bringing in a “fresh perspective.” Instead, they wanted, yet again, a leader more familiar with the district’s inner workings -- and functional turmoil. Described as “an LAUSD man through and through,” 38-year LAUSD veteran Antón succeeded the guy who beat him to the top job just three years earlier. He began his career as a teacher at Rowan Avenue Elementary School. Antón was the first Latino to head the Los Angeles school district, in which more than 60% of the 640,000 students were Latino.

Antón was admired for his fair, straightforward though demanding approach. Among his priorities were relations with parents and looking out especially for minority students in a system that did not always have high expectations of them.

Alas, his inside experience proved insufficient. In the middle of struggling to keep the district solvent despite multibillion-dollar budget deficits, Anton abruptly resigned after only 26 months on the job. On his way out the door, he cited a politically charged atmosphere that included a micromanaging school board and an activist teachers union.

1992-1997

Sidney A. Thompson - INSIDER

LAUSD Supt. Sidney Thompson.

LAUSD Supt. Sidney Thompson. (L.A. Times file photo)

Thompson was also an LAUSD veteran. He started as a math teacher in Pacoima nearly 40 years before becoming superintendent. He was the first African American superintendent to lead the nation’s second-largest school district.

In a farewell editorial about his tenure, The Times’ editorial board wrote that Thompson “deserves credit for his fiscal management, supporting the LEARN [Los Angeles Educational Alliance for Restructuring Now] reforms, getting the teachers to agree to a 3-year contract and stiffening high school courses.”

Thompson initiated a plan that aimed to boost academic performance by the year 2000, including measures such as ensuring all students can read by the end of third grade, enrolling most students in middle-school algebra classes and moving bilingual education students into mainstream English courses after five years. In addition to the ongoing budget and union battles, groups in different parts of the school system were trying to break away and form their own districts. After his nearly four-year tenure as superintendent, he said he learned that reforming a large school system is a job with no natural conclusion.

1997-2000

Ruben Zacarias - INSIDER

Rubin Zacarias, LAUSD superintendent from 1997-2000.

Rubin Zacarias, LAUSD superintendent from 1997-2000. (L.A. Times file photo)

Zacarias was the fourth superintendent over the course of a decade, the first fluent Spanish speaker and the second Latino to run LAUSD. He had worked at every level in the system, including temporary preschool teacher, principal, regional administrator and on up. He started his LAUSD career in 1966 as a teacher at his alma mater, Breed Street School, later becoming principal there in 1975.

When he was appointed, Zacarias vowed he would improve student performance by making teachers and principals personally responsible for school achievement. On his way out, critics called his accomplishments incremental.

Ultimately, Zacarias was pressured into taking a buyout when a newly elected board decided to hire its own choice for district leader. Until Zacarias agreed to leave, however, loyal Eastside supporters staged protests on his behalf.

He was “widely regarded as an insider who was unwilling or unable to challenge colleagues with whom he spent his entire career,” according to a 2015 Times story.

2000

Ramon Cortines - OUTSIDER

Ramon Cortines, who was interim superintendent in 2000.

Ramon Cortines, who was interim superintendent in 2000. (L.A. Times file photo)

The first time LAUSD brought in Cortines, he was hired on an interim basis. He arrived as a 67-year-old outsider who had led districts around the country, including Pasadena, San Francisco (his hometown) and New York. He had a reputation for standing up to board members and bulldozing through bureaucracy, in the name of what he deemed best for students. He was a nationally known educator, and a familiar figure in Pasadena -- where he twice headed the schools -- but new to Los Angeles Unified.

It seems that he was chosen for his ability to get the district running smoothly after Zacarias was pushed out. “If it's truly a cleanup operation to get the district ready for a long-term strategy, then I think he's excellent for this," a UC Berkeley education professor said when Cortines was hired.

He introduced a plan to cut central staff and reorganize, but wasn’t able to see it through in his six-month stint. Cortines also oversaw a back-to-basics agenda that focused on cleaning bathrooms and providing all students with textbooks. And he made all elementary schools adopt a phonics-based reading program. The board urged Cortines to stay, but he left “to avoid any impression that he'd been angling for the job,” according to a 2008 Times story.

2000-2006

Roy Romer - OUTSIDER

Roy Romer, superintendent from 2000-2006

Roy Romer, superintendent from 2000-2006. (L.A. Times file photo)

“Romer was hired in part because he was the only one of five favored candidates who wanted the job,” reads a 2006 Times story published after the former Colorado governor left the job. He came in with the goal of implementing Cortines’ plan to decentralize the district, and to build new schools and facilities for the growing number of students.

Romer sometimes clashed with the board over union relations and over his otherwise-popular $19-billion school repair and construction project. He also had an antagonistic relationship with then-mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, who frequently attacked the district.

Romer has had the longest tenure in the 21st century, and left of his own accord. "You have a whole lot of social and economic pressures,” he said in 2015. “Los Angeles is especially tough because it's so large, so diverse.”

2006-2008

David L. Brewer III - OUTSIDER

Navy Vice Adm. David L. Brewer III, superintendent from 2006-2008

Navy Vice Adm. David L. Brewer III, superintendent from 2006-2008. (L.A. Times file photo)

The school board hired Brewer, a retired Navy admiral, during a leadership struggle over control of the school system with then-Mayor Villaraigosa. Brewer had no experience managing school districts and little preparation for the turmoil of L.A. politics or district infighting.

“In hiring Brewer, board members had opted for a non-educator -- largely because they sought a fresh thinker, unwedded to the bureaucracy, unafraid to make bold, even unorthodox moves,” reads a 2008 Times story.

One of his first moves was to commission a report detailing everything wrong with the district.

Brewer launched an innovation division and test scores continued their gradual rise during his term. Voters also passed a $7-billion school construction bond on his watch. But critics said he moved slowly and never mastered either L.A. politics or district bureaucracy. He was bought out for $517,500.

2009-2011

Ramon Cortines - INSIDER (by now)

Ramon Cortines, superintendent again from 2009-2011

Ramon Cortines, superintendent again from 2009-2011 (L.A. Times file photo)

The second time the school board chose Cortines, they wanted the same bold moves they sought from Brewer, but from an educator who had become familiar with the district and who worked quickly and relentlessly.

Over 2½ years, Cortines trimmed the central office through layoffs and reorganization, managed budget cuts prompted by a statewide economic recession and oversaw a program through which groups from inside and outside the school system could bid for control of low-performing campuses. As a result, more independently run charter schools began to operate on district properties, sometimes sharing sites with traditional public schools. Cortines re-staffed some low-performing schools, requiring teachers there to re-apply for their jobs.

But for Villaraigosa and his allies, Cortines was not moving quickly enough. And in April 2011, Cortines agreed to step aside.

2011-2014

John D. Deasy - OUTSIDER

John Deasy, superintendent from 2011-2014

John Deasy, superintendent from 2011-2014. (L.A. Times file photo)

Deasy came in with ties to local power players like billionaire philanthropist Eli Broad and Villaraigosa. He was familiar with Los Angeles as he had headed the Santa Monica-Malibu Unified School District from 2001-2006, though he hadn’t worked in LAUSD before Cortines hired him.

He was technically promoted from within, since he was Cortines’ top deputy for five months, but was hired with the understanding that he would soon take the top job. The board selected him with little to no outside input, and didn’t have a public search or application process.

Deasy pursued an aggressive agenda that included revamping teacher evaluations and ending the near-automatic granting of tenure to teachers near the end of their second year of work. He also took part in ongoing litigation to limit teacher job protections and to end the use of seniority as a basis for laying off teachers. In addition, he ordered administrators to sharply reduce the number of student suspensions.

His efforts were hindered by a persistent economic recession and deteriorating relations with a majority of board members and the teachers union. Critics blamed him for two technology debacles: a malfunctioning student records system and an aborted $1.3-billion effort to provide every student with an iPad. As with other recent superintendents, test scores rose incrementally.

2014-2015

Ramon Cortines - INSIDER

Ramon Cortines during his final superintendent run, in 2015.

Ramon Cortines during his final superintendent run, in 2015. (L.A. Times file photo)

By this point, Cortines had become the district’s go-to cleanup guy. The board brought him back even though his reputation had been tarnished by a sexual-harassment allegation dating from 2010. Cortines denied wrongdoing. After Deasy’s disastrous departure from the district, the school board wanted an experienced leader they trusted.

Cortines, by then 82, soon told the board he would stay only through 2015. In that year, he smoothed union relations, ended efforts to provide every student with a computer—calling it unaffordable--and oversaw the repair of the student records system.

2016-

Michelle King - INSIDER

Michelle King, the new L.A. Unified School District superintendent.

Michelle King, the newly appointed superintendent. (Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

Following a nationwide search, this week, the school board promoted the consummate insider. Board president Steve Zimmer presented her to Angelenos at a meeting on Monday, calling her a “daughter of our city,” in both Spanish and English. She is the first African American woman to lead L.A. Unified.

King started her career as a secondary life science teacher at Porter Junior High School in 1984. After serving as a principal, she served in a succession of district roles before winding up as chief deputy superintendent. She served as the No. 2 administrator for both Deasy and then Cortines in his latest stint.

She will inherit the problems that have plagued superintendents before her, and a few new ones. Enrollment is declining, the district faces a deficit, and there’s an effort to dramatically increase the number of charter schools in the city. Only time will tell whether her intimate familiarity with the district will help her succeed where others before her have failed.

Interested in education? School me: @mmaltaisla

Times Reporter Howard Blume contributed to this report.

The Times receives funding for its digital initiative, Education Matters, from one or more of the groups quoted in this article. The California Community Foundation and United Way of Greater Los Angeles administer grants from the Baxter Family Foundation, the Broad Foundation, the California Endowment and the Wasserman Foundation to support this effort. Under terms of the grants, the Times retains complete control over editorial content.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.