Do L.A. Unified’s daily random searches keep students safe, or do they go too far?

Kevin Castillo was in his freshman year at Hamilton High School when administrators carrying hand-held metal detectors interrupted his English class to conduct a random search.

They asked a student to pick a number between 1 and 10. The student chose 7, so every seventh person in the class had to gather up belongings and step out of the classroom.

The chosen students, Kevin among them, were taken to a nearby office, he said, where they were instructed to open their backpacks slowly to allow administrators to look inside. The administrators used sticks to move items around, he said. They also waved the metal-detector wands up and down the students’ bodies.

Kevin didn’t have anything he wasn’t supposed to, he said. His belt had metal in it, but it still startled him when the detector went off.

“I was scared the whole time,” he said.

Some local activists are pushing to end the random searches, saying there is little consistency in the way they are conducted or evidence that they are useful or necessary. The Los Angeles Unified School District’s acting superintendent, Vivian Ekchian, recently said at a public meeting that she planned to commission a districtwide survey of attitudes about the searches.

LAUSD is the only district its size that requires every middle- and high-school campus to conduct daily random searches for weapons using metal-detector wands.

The district started random searches in 1993 after a 16-year-old was shot and killed at Fairfax High School. A month later, a student died from a shooting at Reseda High School.

The district began requiring the daily searches with metal-detector wands in 2011 after two students were injured in a shooting at Gardena High School, district officials said.

Do the searches work?

An internal district audit of 20 schools released in April found inconsistencies in how random searches were done. Some schools didn’t do the searches daily, the audit found. One-fourth didn’t have enough metal-detector wands to search properly.

Interviews with teachers, students and administrators also indicate that elements of the searches — from who gets picked to be searched to how the search is done — are not uniform across the school system.

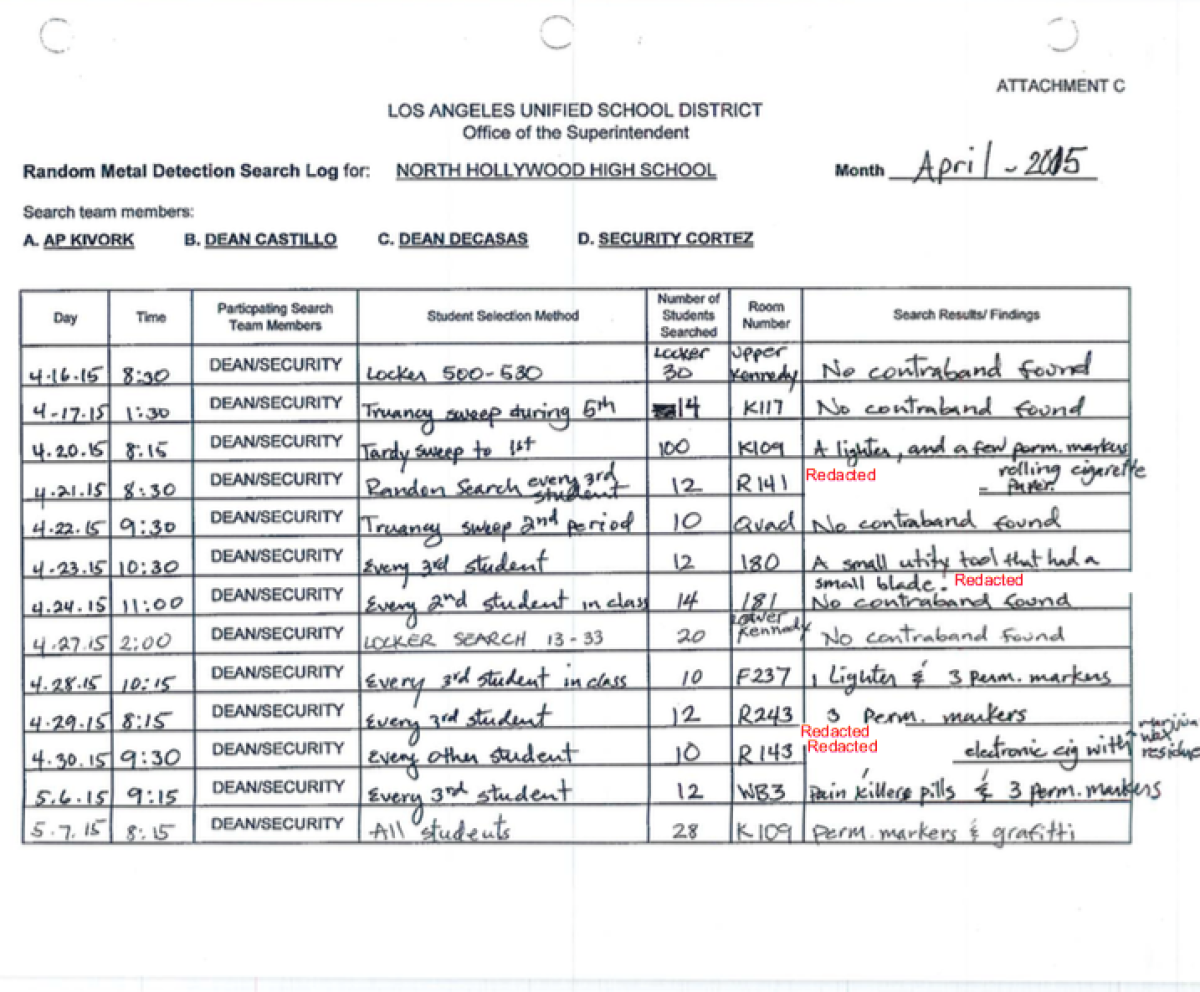

The nonprofit InnerCity Struggle, which works to promote safe, healthy communities on L.A.’s Eastside, and the advocacy law firm Public Counsel asked the district for logs of random searches at schools where weapons had been confiscated. The district provided them with logs for 59 schools, fewer than a quarter of the middle and high schools. The records may not show all the searches at those 59 schools because they asked for logs only when weapons were found.

UCLA’s Civil Rights Project recently analyzed those records of searches conducted from 2013 to 2015, and determined that they cover about 5,400 searches, with about 34,000 searches of students. Administrators, according to the analysis, confiscated many more school supplies than they did guns (0) and knives (37) during random searches.

Among the nonweapon items confiscated, according to the partial records: 1,112 markers, 241 lighters, 137 pairs of scissors,109 body sprays, 80 bottles of correction fluid, 73 illegal drugs, 56 over-the-counter medications and 34 highlighters.

When Kevin, now 17, was last searched in April, administrators saw that he was carrying playing cards and asked if he gambled, he said.

“It was already assumed that I did negative things just because of a deck of cards,” he said. “But I don’t gamble. I was just doing card tricks.”

Where are the weapons?

The low weapons numbers show the searches are having the intended effect, L.A. Unified lawyer Katrina Campbell said.

“The beauty of wanding is that it acts as a deterrent,” she said, “and so the number of weapons recovered … we would expect that number to be very, very low.”

School board members are split on the topic. Some say parents want to see random searches continue, while others question the efficacy and the effect on students.

Student school board member Benjamin Holtzman, also a Hamilton student, said in a recent school board session that he supports the searches despite their inconvenience because he believes they are a valid safety measure.

Student activists and advocates, however, say the low numbers support their claim that the searches are a waste of time and an intrusion that destroys trust between students and school staff.

“Students come to school … to learn, to have a better education and to be able to have a better idea of what we’re going to do with our lives,” said Guadalupe Morales, 16, of Mendez High School. The searches don’t make her feel safer, she said. Rather, she said, they make her feel powerless, and afraid of the adults she is supposed to be learning from.

The searches especially worry LGBT youth and students who fear deportation, said Rocque Armenta, a senior strategy director at InnerCity Struggle. Homeless students who carry all their belongings with them also can find them frightening.

There’s been little research on the effect of daily random searches in schools, UCLA education professor Sandra Graham said. But “schools [begin] to look more like prisons where there’s a lot of surveillance. …This can lead for kids to greater negative perceptions of the school climate.”

Some students also carry weapons to feel safe walking to and from school, said Amir Whitaker, a lawyer and former UCLA Civil Rights Project researcher, who led the analysis.

Advocates call for more mental health counselors and restorative justice coordinators to address the underlying issues that lead students to bring weapons to school in the first place.

What do random searches look like?

District administrators did not allow a reporter to observe a random search. Instead they pointed to a recent school board study session in which George Washington Preparatory High School administrators did a demonstration.

According to the data from the UCLA analysis, schools choose an average of six students a search. But that number can vary widely. In 2015, North Hollywood High School randomly searched 100 students on April 20, a day on which many people celebrate marijuana. They found one lighter and a few permanent markers, according to the records, but no drugs.

The date combined with the high number of students searched suggest that the administrators sometimes abuse the search policy to look for drugs, Whitaker said.

They also chose to search students who were late to class that day — a form of targeting, Whitaker said.

Campbell, the district lawyer, said the random searches are “not used to detect drugs” but added, “If we inadvertently discover that a student has drugs, yes, we do have an obligation to retrieve that illegal object.”

Some district teachers and students say that searches are less common in advanced-placement, honors and magnet classrooms. Those classes often have more white students than other classes, which means nonwhite students could be targeted more frequently.

Although schools are required to keep logs of searches and include anything that was confiscated, they do not record what type of class is searched or the gender or race of students searched. Campbell said the district has no evidence that magnet schools and AP classes are not being searched regularly.

Some school staff say they have never received training about the searches.

The first time English teacher Sharonne Hapuarachy’s class at Dorsey High School was searched, administrators told students to put their hands on their desks. Thinking she might be searched, too, Hapuarachy followed suit.

Administrators, she said, “have never ever told the faculty a word about it, explained what they’re doing, why they’re doing it.”

The L.A. Unified logs that UCLA analyzed show at least 80 searches at Dorsey from 2013 to the end of the 2015 school year. In some 2013 Dorsey logs, administrators wrote that the method they used to choose students was “visual.” Often, they searched an entire class.

Sherlett Hendy Newbill, Dorsey’s dean, said she or another administrator now pick a classroom in a building they haven’t visited in a while. Before choosing every fifth student, she will ask if anyone has anything to hand over.

Random searches happen only about once every few months at Dorsey, said Hendy Newbill, who was not a dean from 2013 to 2015.

She wasn’t aware that they were supposed to be daily, she said. “We don’t have the manpower to do that every day.”

Times data desk editor Ben Welsh contributed to this report.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.