What’s different about the latest wave of college activism

After several days of protesting Occidental College’s handling of diversity issues, students occupied an administrative building, demanding that the school President Jonathan Veitch step down.

If the University of Missouri was the spark, then the fire didn’t take long to spread.

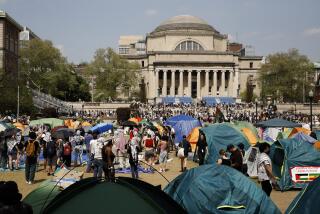

Since the resignation of its president and chancellor Nov. 9, protesters have organized at more than 100 colleges and universities nationwide. Social media sites have lighted up with voices of dissent, and what began as a grievance has evolved into a movement.

Inspired by the marches in Ferguson, Mo., and Black Lives Matter, students are taking to social media to question the institutions they once approached for answers.

Calling for racial and social reforms on their campuses, they are borrowing tactics of the past — hunger strikes, sit-ins and lists of demands — and have found a collective voice to address their frustrations, hurt and rage.

Their actions seem to have hit the mark.

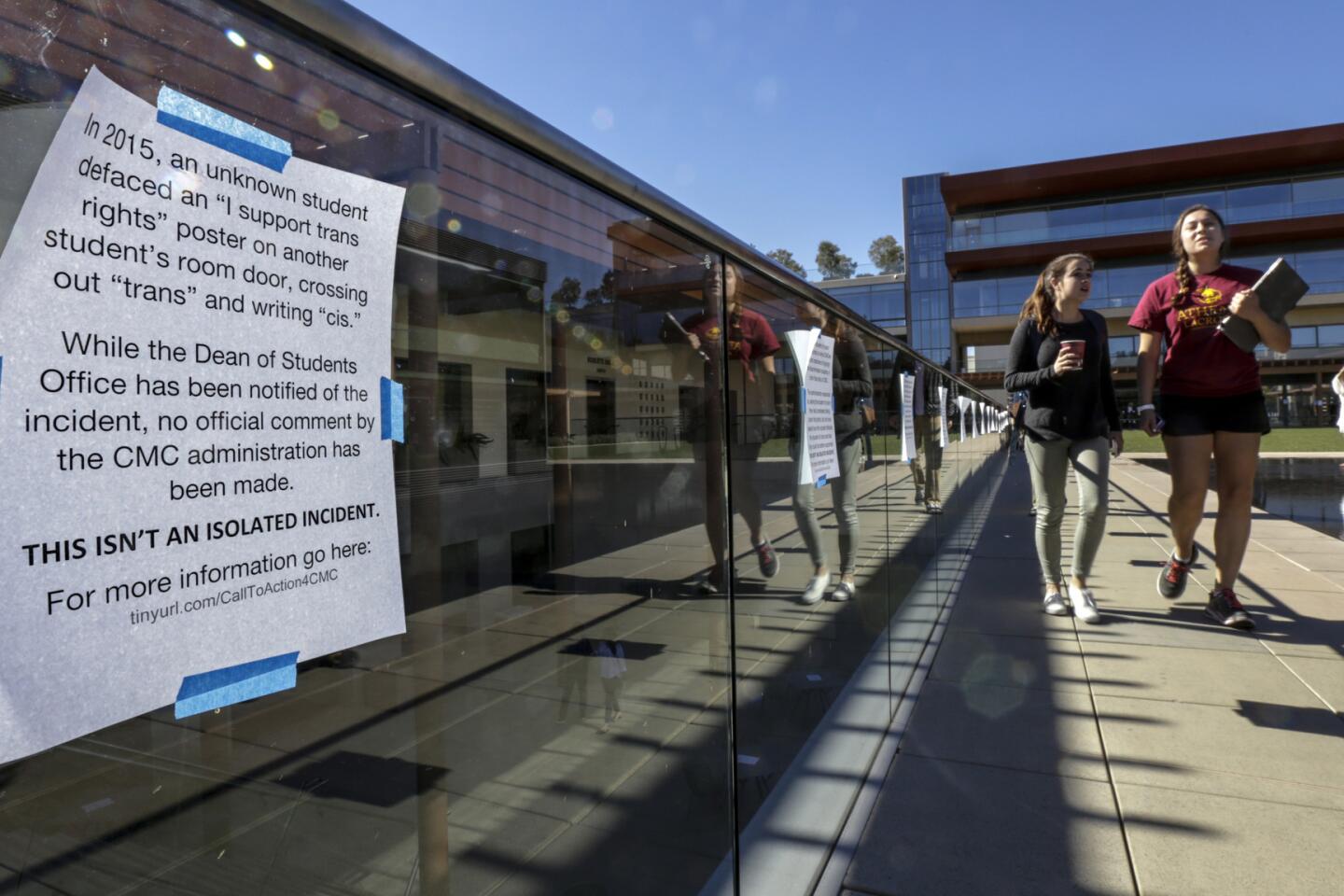

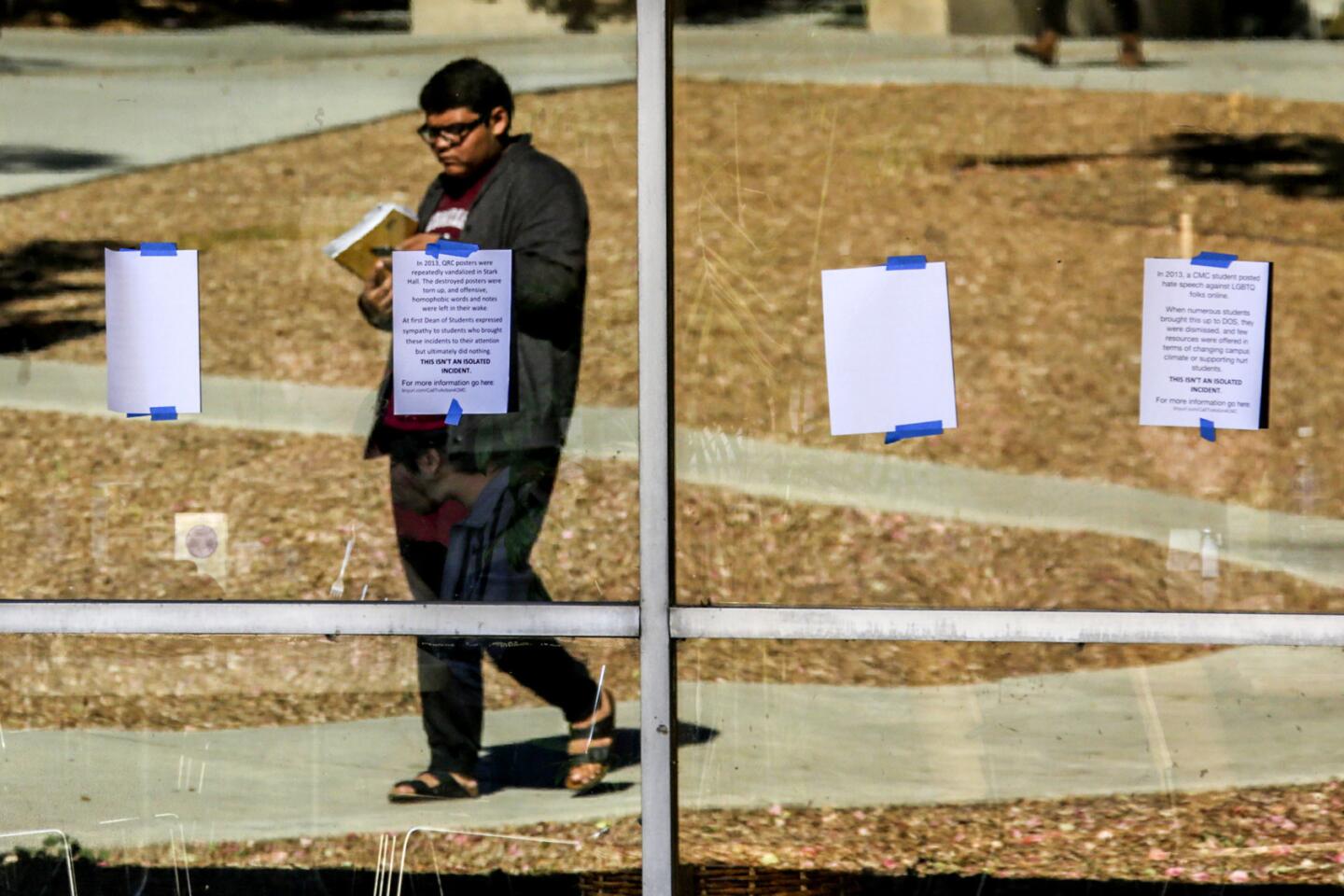

Last week, the dean of students at Claremont McKenna College left the university after students protested her comments to a Latina student with the offer to work for those who “don’t fit our CMC mold.”

Tuesday night, Jonathan Veitch, the president of Occidental College, said he and other administrators were open to considering a list of 14 reforms, including the creation of a black studies major and more diversity training, that student protesters had drawn up.

Students at USC have similarly proposed a campuswide action plan, which includes the appointment of a top administrator to promote diversity, equity and inclusion.

Nationwide, complaints of racism and microaggression are feeding Facebook pages and websites at Harvard, Brown, Columbia and Willamette universities, as well as at Oberlin, Dartmouth and Swarthmore colleges.

Protesters at Ithaca College staged a walkout to demand the president’s resignation, and Peter Salovey, president of Yale University, announced a number of steps, including the appointment of a deputy dean of diversity, to work toward “a better, more diverse, and more inclusive Yale.”

For decades, students have helped drive social change in America, if not the world. Campuses, said University of California President Janet Napolitano, have “historically been places where social issues in the United States are raised and where many voices are heard.”

Over the decades, student protests have shifted attitudes in the country on civil rights and the Vietnam War, nuclear proliferation and apartheid, and some of today’s actions are borrowing from tactics of the past.

Although some of the strategies may seem familiar, it is the speed and the urgency of today’s protests that are different.

“What is unique about these issues is how social media has changed the way protests take place on college campuses,” said Tyrone Howard, associate dean of equity, diversity and inclusion at UCLA. “A protest goes viral in no time flat. With Instagram and Twitter, you’re in an immediate news cycle. This was not how it was 20 or 30 years ago.”

Howard also believes that the effectiveness of the actions at the University of Missouri has encouraged students on other campuses to raise their voices.

The Times’ new education initiative to inform parents, educators and students across California >>

“A president stepping down is a huge step,” he said. “Students elsewhere have to wonder, ‘Wow, if that can happen there, why can’t we bring out our issues to the forefront as well?’”

Shaun R. Harper, executive director of the University of Pennsylvania’s Center for the Study of Race and Equity in Education, agrees. The resignation of two top Missouri administrators, Harper said, showed students and athletes around the country that they have power they may not have realized before.

The protests show “we’re all together and we have the power to make the change we deserve,” said Lindsay Opoku-Acheampong, a senior studying biology at Occidental.

“It’s affirming,” said Dalin Celamy, also a senior at the college. “It lets us know we’re not crazy; it’s happening to people who are just like you all over the country.”

Celamy, along with other students, not only watched the unfolding protests across the country, but also looked to earlier protests, including an occupation of an administrative building at Occidental in 1968.

Echoes of the 1960s in today’s actions are clear, said Robert Cohen, a history professor at New York University and author of “Freedom’s Orator,” a biography of Mario Savio, who led the Free Speech Movement at UC Berkeley in the 1960s.

Today’s protests, like those in the ‘60s, are memorable because they have been effective in pushing for change and sparking dialogue as well as polarization.

— Robert Cohen, a New York University history professor

“The tactical dynamism of these nonviolent protests and the public criticism of them are in important ways reminiscent of the 1960s,” Cohen said. “Today’s protests, like those in the ‘60s, are memorable because they have been effective in pushing for change and sparking dialogue as well as polarization.”

Although the targets of these protests are the blatant and subtle forms of racism and inequity that affect the students’ lives, the message of the protests resonates with the recent incidents of intolerance and racial inequity on the streets of America.

There is a reason for this, Howard said.

Campuses are microcosms of society, he said, and are often comparable in terms of representation and opportunity. “So there is a similar fight for more representation, acceptance and inclusion.”

The dynamic can create a complicated and sensitive social order for students of color to negotiate.

“Latino and African American students are often under the belief if they leave their community and go to colleges, that it will be better,” Howard said. “They believe it will be an upgrade over the challenges that they saw in underserved and understaffed schools. But if the colleges and universities are the same as those schools, then there is disappointment and frustration.”

In addition, Howard said, when these students leave their community to go to a university, they often feel conflicted.

“So when injustice comes up,” he said, “they are quick to respond because it is what they saw in their community. On some level, it is their chance to let their parents and peers know that they have not forgotten the struggle in the community.”

On campuses and off, Harper, of the University of Pennsylvania center, finds a rising sense of impatience among African Americans about social change. “As a black person, I think black people are just fed up. It’s time out for ignoring these issues,” he said.

While protests in the 1960s helped create specific safeguards for universities today, such as Title IX, guaranteeing equal access for all students to any educational program or activity receiving federal financial assistance, a gap has widened over the years between students and administrators over perceptions of bias.

Institutions often valued for their support of free speech find themselves wrestling with the prospect of limiting free speech, but to focus on what is or isn’t politically correct avoids the more important issue, Cohen said: whether campuses are diverse enough or how to reduce racism.

Occidental student Raihana Haynes-Venerable has heard criticism that modern students are too sensitive, but she argues that subtle forms of discrimination still have a profound effect.

She pointed to women making less than men and fewer minorities getting jobs as examples.

“This is the new form of racism,” she said.

MORE EDUCATION COVERAGE

Backlash brews against student race protests at Claremont McKenna College

Nonprofit is formed to advance charter-school plan in Los Angeles area

Board tweaks qualities for next LAUSD chief down to a T

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.