California’s students stagnate on standardized tests — but the lowest scorers are improving

When California rolled out new standardized tests, experts said scores would improve when students got used to them. But three tests in, rather than showing strides from familiarity, their scores have stagnated in English and math.

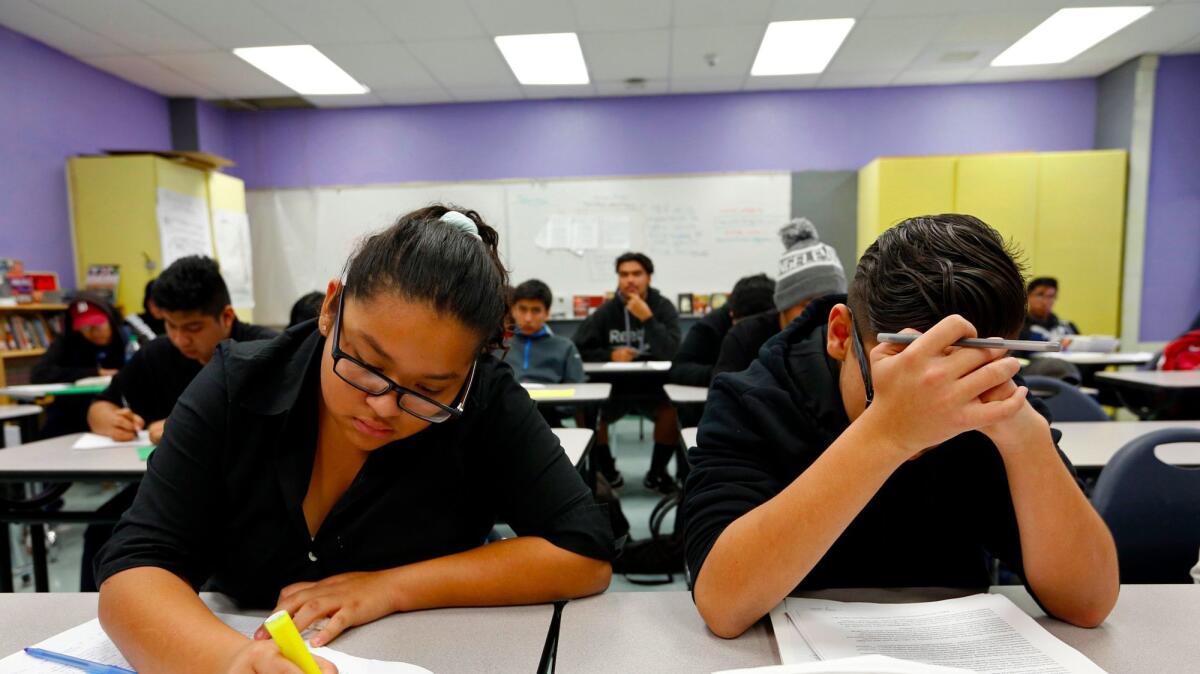

About 3.2 million students in third through eighth grade and 11th grade took the California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress in the spring. The tests are aligned to the Common Core standards, and demand mastery — which means they’re harder than California’s old standardized tests.

This year, 49% of students passed the English exam, compared with 48% in 2016. In math, 38% of students met or exceeded the state’s standard, compared with 37% last year. Fifth-graders’ scores dropped slightly in English.

The previous year, students’ scores had improved in both subjects, prompting California’s State Supt. of Public Instruction Tom Torlakson to travel from Sacramento to Los Angeles and hold a news conference to highlight the gains.

This year, he issued a statement describing the results as sustained progress.

The new scores, released Wednesday, pave the way for state education officials to accomplish a key task: to identify — and then intervene to improve — the most underperforming schools.

The Every Student Succeeds Act, a federal law, requires states to identify the bottom 5% of their schools that serve low-income students and then take steps to turn them around. California can expect to get $2.6 billion from the federal government for complying with the law, mostly to help children from low-income families.

But the state doesn’t yet have a detailed plan for defining the lowest performers.

Based on the test scores, The Times has assembled its own list of schools that fell to the bottom 5% in 2015, the first year of testing.

They are scattered around the state but include 50 in South Los Angeles.

Looking at how those schools have fared in recent years, The Times found both good news and bad.

Over the last two years, these schools posted larger gains than the state as a whole. But a handful also slipped further behind.

The Times identified 451 schools that were in the bottom 5% in 2015. An average of 7% of their students hit math goals that year; 12% did so in English. By 2017, 11% reached math and 19% reached English standards. Progress in English was almost double the state rate. And nearly half of these schools moved up and out of the lowest scoring 5% by this year.

But many were still stuck on the bottom rungs two years later. And about 60 schools’ scores got worse.

“It’s dangerous to have schools that may need assistance and support from the state and no guarantee that the states will provide any direction,” said Ryan Smith, the executive director of the Education Trust-West, an Oakland-based nonprofit that advocates for educational equity. “We need to sound the alarm.”

Test scores are by no means the only way to measure a school’s academic achievement, which is something California tries to take into account. The state has veered away from showcasing numbers. Instead, it translates test scores into colors — green for the best, red for the worst — and presents numerous color-coded measures of school success, including graduation and suspension rates and college and career readiness. They can be found on the California School Dashboard, a new digital school grading tool.

The dashboard ultimately is supposed to form the backbone of the state’s ranking system. But all the colors can sometimes obscure specific problems.

State officials have said that they will do their own complex calculations to identify the bottom 5% of schools in academics. The Times analysis looked at the percentage of students meeting or exceeding goals, and how those numbers changed over time.

The school in the bottom 5% that dropped the most from 2015 is Castlemont High School in Oakland Unified, where students meeting goals fell from 16% in English and 4% in math to 1.25% proficient in English and 1.16% in math.

But Castlemont is a textbook example of why test scores alone don’t paint a complete picture: as is often the case when they rise or fall dramatically, demographic changes are at work.

Castlemont is one of several Oakland schools that have experienced an influx of students who recently emmigrated from Central America, many of them arriving with no English and little formal schooling.

In 2014, over the span of about six months, Castlemont’s newcomer population rose by 200 students, said Nicole Knight, executive director of Oakland Unified’s English Language Learner and Multilingual Achievement Office. Ultimately, Knight said, the school will serve about 300 newcomers.

For their first year in the U.S., newcomers are not subjected to California’s standardized exams. But from that point on, they are required to take them.

These students, Knight said, “are fleeing from unimaginable trauma and violence” and face difficulty as they adjust to life in Oakland. In addition to classwork, newcomer students often take on adult responsibilities such as paying rent, supporting family members and trying to win asylum.

High teacher turnover also could have been a factor at Castlemont, said Oakland Unified spokesman John Sasaki. The school is focused on improving, he said, and expects better results on the next round of standardized tests.

In L.A. Unified, like the rest of the state, students posted flat scores in English and math.

This year, 40% of district students met or exceeded the state standard in English, compared with 39% in 2016. About 30% of district students passed the state’s math exam, compared with 29% last year.

“It’s moving in the right direction, but we’re not completely satisfied,” said Oscar Lafarga, executive director of the district’s Office of Data and Accountability.

One of the bottom 5% schools that fell the most within L.A. Unified is John W. Mack Elementary, a school in South L.A. that serves many English-language learners.

In 2015, 12% of Mack students met goals in each subject. This year, 7% did.

The school presents itself as a welcoming haven for neighborhood families. Its website hosts a podcast and features the “Mack Squad News.” It also showcases student art, including a collage of bright pink and yellow homes and palm trees.

District officials say the school’s low scores caught their attention two years ago, during a reorganization. They hired a new principal, who has focused on helping students and parents who are learning English, partnering with USC and Loyola Marymount University, and developing a dual-language program, said Natividad Rozsa, a district administrator who oversees Mack.

And there are early marks of improvement, Rozsa said. Scores have risen on internal reading tests given to children in kindergarten through second grade.

“I wish it was straightforward, but it’s complex,” said Rozsa. “If scores went down, we are concerned — but that’s why we’re doing things for them.”

Despite Mack’s significant performance drop, the California School Dashboard classifies its overall academic ranking for math as yellow — translation, average.

“The implication is parents might not get an honest picture of how their students are faring academically by looking at the dashboard,” said Carrie Hahnel, Education Trust-West’s deputy director of research and policy. “It communicates that things are fine where in some cases they are, and in some cases, they’re not.”

There were some bright spots within LAUSD. Several elementary schools — Alta California, Knox and Woodcrest — made enough progress to move out of the bottom 5% group. In 2015, these schools had single-digit percentages of students meeting or exceeding goals. Those scores jumped about 10 to 15 percentage points in 2017.

[email protected] | Twitter: @joy_resmovits

[email protected] | Twitter: @annamphillips

[email protected] | Twitter: @palewire

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.