Women’s testimony called ‘blueprint’ to serial killer suspect’s behavior

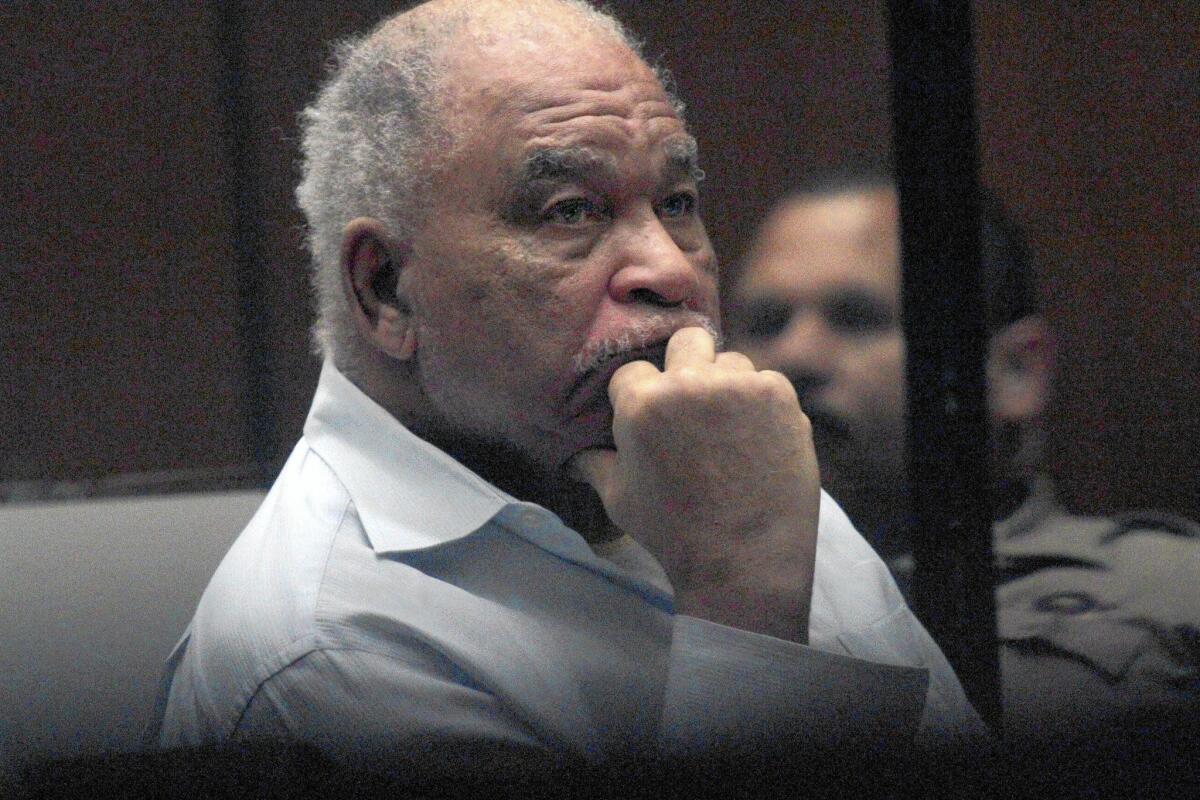

Samuel Little, a 74-year-old man with slumped shoulders and curly silver hair around a bald spot, has been sitting in a wheelchair in a downtown L.A. courtroom for the last two weeks, impassively listening to accusations that he killed three women.

On the overhead screen, decades-old photos flashed by of a younger Little, his head cocked to one side and peering down at the camera. He was 6 feet 3 then, weighing more than 200 pounds, with broad, sturdy-looking shoulders.

That younger man, a prosecutor argued, preyed on vulnerable woman in cocaine-ravaged South L.A. After more than three decades, the crimes have caught up with him, she said — his DNA was found on the bodies of three women whose bodies were dumped within a few miles of each other in 1987 and 1989, all beaten and strangled.

On top of the forensic evidence, the prosecutor offered up testimony from women who she said were the ones that had gotten away, ones who had also been attacked by Little years ago but escaped with their lives. The women flew in from around the country to tell stories they long believed no one would care to hear, and each picked out the aging man without hesitation as her assailant.

They testified that they remembered his large hands, the blows he dealt with them and the feeling of them closing around their necks.

“It tells you exactly what happened in this case.... It’s a blueprint,” Deputy Dist. Atty. Beth Silverman said in closing arguments Friday. “This is a man … who believes he can take whatever he wants from women.”

::

First to tell her story was Hilda, now a 60-year-old grandmother with salt-and-pepper hair, pearl earrings and a billowing skirt. (The Times is withholding the women’s last names to protect the privacy of victims of sexual assault.)

In 1980, she was living in the Carver Village housing projects in Pascagoula, Miss. Women who worked as prostitutes along one street known as “the Front” looked out for one another — if someone wasn’t back in 15 minutes, they would go check on her.

In July of that year, a man she identified in court as Little picked her up outside a nightclub and she led him back to her apartment. As soon as the door closed behind them, Hilda testified, he went for her neck and started choking her, then knocked her out with a punch.

She said she awoke on her bed with the man straddling her, choking and beating her. She next came to submerged in water in her bathtub, naked except for a scarf around her neck. The man, she said, would yank her head out of the water with the scarf, punch her face some more, then push her back underwater.

In and out of consciousness, she said she eventually woke to find herself at the hospital, unable to talk and the whites of her eyes crimson. She told hospital staff and police that she’d been attacked by a burglar. Her parents were with her at the hospital, and they didn’t know how she’d been making ends meet for herself and her children.

::

In November 1981, Lelia was about 20 years old and raising three children on her own. She hustled shoes out of the trunk of her car, rented out rooms in the back of a nightclub to women who walked the Front, and turned tricks herself.

The week before Thanksgiving, she was walking along the Front one night when a man in a station wagon with wood paneling pulled up and asked for a “date.” She quoted him $50.

She got into the car and the man drove off. With his right hand still on the steering wheel, the man “cold cocked” her on the back of her head, then punched her between her eyes, she said. He began choking her — she resisted, scratching and biting him.

She managed to escape from the car a few times — but each time, he would drag her back, “like ring around the rosies, in and out,” she testified. One of those times, a white boy on a bicycle saw her and asked if she needed help. She opened her mouth, but no sound came out from the choking.

“She’s just drunk. That’s my old lady,” her attacker told the boy, Lelia recalled in her testimony.

She wriggled her way into the cargo area of the car and squeezed out through the back. Clad only in shorts and flip-flops, stripped of her halter top in the struggle, she ran straight across Highway 90. She knew the midnight shift at the shipyard was about to let out and flood the streets with workers heading home. She did not stop running until she was back in the village.

People took her to the hospital, where blood seeped from her eyes like tears and she couldn’t swallow for two weeks. No police came to the hospital, and she made no report.

“They don’t care nothing about no black prostitute in Pascagoula,” she said. The night just became one of the many war stories she traded with other women.

::

Laurie had also at times worked as a prostitute, but she wasn’t looking for work the night she encountered Little in San Diego, in September 1984. She was walking up to a friend’s apartment when a man put his arm around her throat in a chokehold and pulled her inside a dark-colored car.

Even after the decades, she remembered the interior of the car vividly — fuzzy dice hanging from the rearview mirror, driving knobs on the steering wheel and shiny, maroon-colored vinyl seats.

With his arm still wrapped around her neck, he drove to a deserted trash-strewn lot at the top of a steep hill. He pulled her into the back seat and tied her hands behind her back with her nylons, she testified. He tried to kiss her, and when she tried to shove him off, he began choking her.

He asked her to swallow.

“He liked to feel me swallow with his thumb on my neck,” she told jurors. “It became a game — right before I’d go unconscious, as my eyes started rolling back, he’d let go and ask me to swallow again.”

The man eventually pushed her out onto a heap of trash. She made her way to a friend’s apartment where she sat in the tub for an hour before calling the police at the friend’s insistence. Police took her to the hospital, where doctors found her bruised from head to toe, eyes hemorrhaged, ligature marks on her neck.

For the attack on Laurie and another San Diego woman, Little was convicted of assault and false imprisonment and served 2 1/2 years in prison.

::

Little showed almost no emotion throughout the women’s testimony, occasionally whispering to his public defender. His attorney, Michael Pentz, accused prosecutors of parading in front of jurors “disturbing” stories and images unrelated to the slayings his client is on trial for.

“Most of what you heard was about his past,” he told jurors Friday, arguing that the DNA evidence was insufficient to prove Little killed the three women.

Those women were introduced to jurors as lifeless bodies in yellowing crime scene photographs, each of them nude save for a shirt or sweater bunched up around their shoulders, with signs of strangulation.

Carol Alford was found July 13, 1987, in a South L.A. alley, against a fence. Audrey Nelson was found Aug. 14, 1989, in a dumpster in a parking lot behind a club and restaurant. Guadalupe Apodaca was discovered on Sept. 3, 1989, in an abandoned commercial garage. Jurors are set to begin deliberating the case Tuesday.

All of the women — dead and alive — had one thing in common, Silverman told jurors. “They were women who law enforcement at the time were unlikely to take seriously,” she said.

After Lelia finished testifying and headed for the courtroom door, a man approached. It was Apodaca’s son. He thanked her and gave her a hug.

Patting him on the back, she told him: “I spoke for her.”

Twitter: @vicjkim

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.