Doctor with revoked license continues to sell unproven stem cell treatments

Last fall, two decades after Malibu psychiatrist William Rader began selling unproven stem cell treatments to desperate patients with incurable conditions, California authorities permanently revoked his medical license for negligence, false or misleading advertising and professional misconduct.

“His dishonesty permeates every aspect of his business and practices,” the medical board wrote in a scathing 39-page decision.

Today, Rader has a new title: “chief scientist” rather than “chief medical officer.” But his California company continues to operate, advertising and arranging injections that cost $30,000 apiece and are administered abroad, outside the reach of U.S. authorities.

As long as the treatments never enter the country and Rader no longer represents himself as a licensed doctor, U.S. regulators are limited in their ability to stop him.

Revoking a doctor’s license is the most severe punishment the medical board can impose.

“We did our job,” said Cassandra Hockenson, a spokeswoman for the board. “He’s done as far as we’re concerned.”

For its part, the Food and Drug Administration, which regulates medications, medical devices and biological products, has no jurisdiction outside the United States.

The Federal Trade Commission, which regulates advertising, can take action against U.S. companies that promote questionable medical treatments abroad. But the most recent example officials there cited was a 1975 case against travel agencies that were promoting trips to the Philippines for “psychic surgery” to treat cancer.

The commission is stretched thin in its efforts to stop misleading advertising of all types.

“There are probably hundreds of thousands if not millions of websites and blogs making suspicious claims,” said Mary Engle, associate director for advertising practices. “We can’t possibly pursue everything.”

Mexican regulators in Tijuana said they were unfamiliar with Rader but that his company would need government permission to operate there.

“It’s illegal to sell something that’s experimental,” said Dr. Sarai Barajas, a Tijuana health official.

Rader, a former Navy psychiatrist, once ran a chain of eating disorder clinics, worked as an on-air medical expert for KABC-TV in Los Angeles, co-wrote an episode of the sitcom “All in the Family” and was married to one of its stars, Sally Struthers.

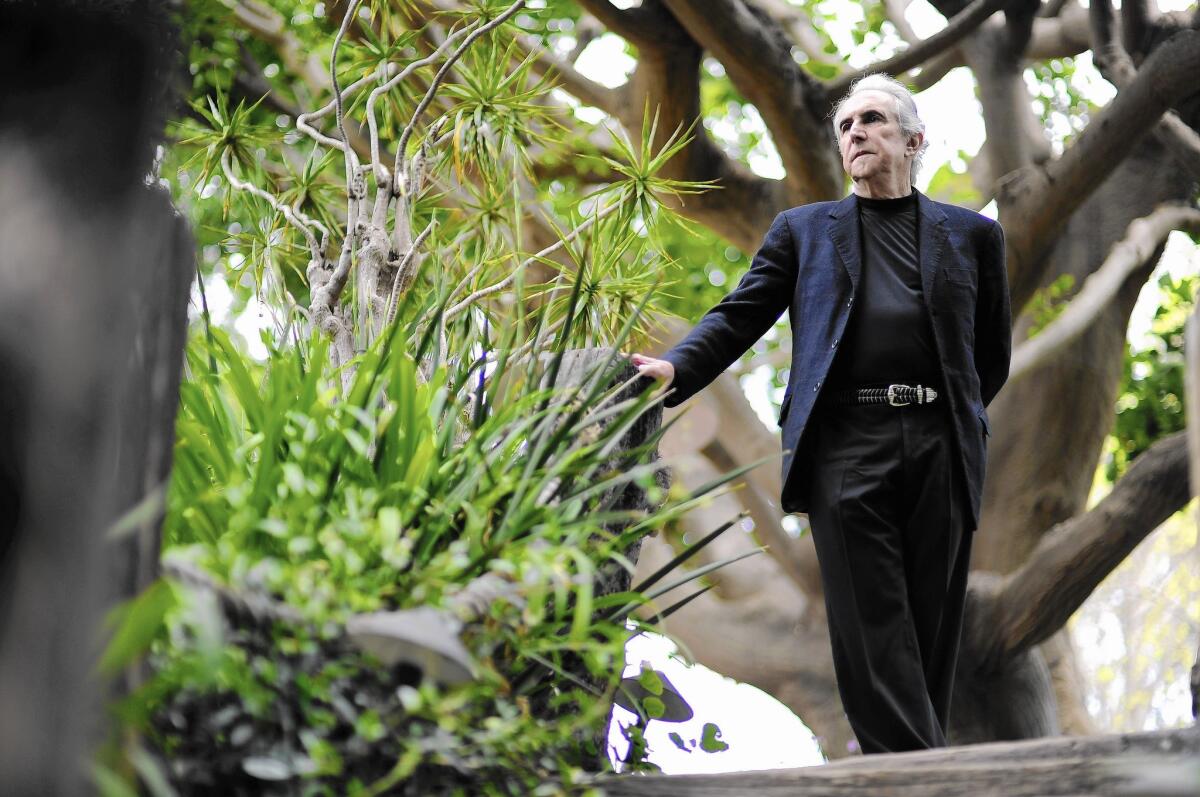

In an interview at his Spanish-style villa in Malibu, Rader, 77, said he was proud to have lost his license. “I must be doing something right,” he said. “The greater percentage of people who get into trouble are ahead of their time.”

Rader has never allowed outsiders to examine his injections and has never published scientific evidence on their efficacy.

Dr. Evan Snyder, head of the stem cell program at the Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute in La Jolla and a vocal critic of Rader, said he was surprised to see him still operating. “He’s like whack-a-mole,” Snyder said.

Rader’s company, Stem Cell of America, operates out of an office in Westlake, selling injections for patients with arthritis, muscular dystrophy, spinal cord injuries and other intractable conditions. Its website, which includes videos of patients and written testimonials from families, advertises “Over 3000 patients treated,” “No known negative side effects” and “No age requirements.”

On a recent morning, a sales representative wearing a headset could be heard recommending a stem cell injection for an eye problem.

One Saturday each month, the company rents space in Tijuana at an alternative medicine clinic called Oxygen. The stem cell patients pay for the treatment in advance or bring certified checks, which are deposited in a U.S. bank account, Rader said. They usually stay at a hotel in San Diego and arrive at the clinic by van.

Rader said that a Mexican anesthesiologist is the company’s medical director and oversees the injections. Rader said he could not remember the doctor’s full name.

The injections are made from aborted fetuses in the former Soviet Republic of Georgia, according to Rader. The treatment, which is the same for every condition, is delivered through an IV and multiple injections under the skin of the abdomen.

Patients sign a consent form acknowledging that results are not guaranteed and agreeing not to discuss the treatment with the media or online without permission from the company.

In deference to the medical board, the form also states that the only doctors involved are Mexican and that Rader “will not be practicing medicine or giving me medical advice or recommendations, but instead solely sharing his observations.”

Rader said he meets patients in Tijuana not as their doctor but as a “PR person representing the company.”

“They like the idea of having me there,” he said. “It’s like having a celebrity there.”

Rader said he had taken the cells himself for their anti-aging properties. He spoke of himself as a humanitarian and scientific pioneer and claimed he had cured a patient of AIDS.

He became interested in stem cells in the mid-1990s after a business contact told him about a company in Ukraine that was injecting patients with solutions made from aborted fetuses, he told The Times in 2005.

He soon began meeting patients in the Bahamas for injections. He later shifted to the Dominican Republic and eventually to Mexico. His company has operated under at least three different names.

Offshore stem cell clinics have proliferated because of the much-touted potential of the cells and confusion over U.S. policy. Restrictions put in place by President George W. Bush — but lifted by President Obama — barred researchers from using federal funds to develop new lines of embryonic stem cells, which are prized for their ability to morph into any type of cell but cannot be harvested without destroying days-old human embryos.

Their power has yet to be turned into viable treatments, which stem cell experts say will not be one size fits all.

Some patients and their families desperate for help, however, have come to believe that the U.S. is denying them cures and that it makes sense to go abroad.

The media have cast doubt on Rader’s practices over the years in reports including a Times story about stem cell entrepreneurs and a BBC documentary that showed hidden camera footage of Rader trying to persuade a woman with multiple sclerosis to go through with the treatment.

The medical board case, filed in 2010, involved two men who received injections. One was paralyzed in a motorcycle crash, the other suffered severe spinal cord damage as a result of a staph infection. Neither experienced any improvement after the treatment.

The family of a third patient, an elderly man with a brain injury, drove him across the country after Rader convinced them that the treatment could help, according to the medical board’s decision. By the time they arrived in San Diego, the man had entered a chronic vegetative state, and the family gave up and drove him back to Alabama, where he died the following month.

In the medical board proceedings, Rader was represented by attorney Robert Shapiro — best known for defending O.J. Simpson against murder charges. Shapiro argued that Rader was not functioning as a doctor to those patients because foreign doctors oversaw the injections. The board disagreed.

The defense also presented four witnesses who testified that the injections had helped: a woman who had kept her leukemia at bay; a woman whose daughter was suffering from lupus and arthritis; a woman with Parkinson’s disease; and a father who believed his daughter’s mitochondrial disease had been mitigated before she died of a heart arrhythmia shortly after her fourth stem cell treatment.

Medical researchers place little stock in testimonials because many conditions can vary day to day, the placebo effect can cause temporary improvement, and wishful thinking can skew perceptions.

Pat Schmidt, the mother of the motorcycle crash victim, launched an online campaign against Rader after the treatment failed.

“The U.S. can’t do a damn thing,” said Schmidt, who lives just outside Baltimore.

Jim Dierkop, the patient with the staph infection, said that after the first injection had no effect and he complained, Rader provided two more failed treatments at no charge. In the Dominican Republic and Mexico, Dierkop saw parents of children with genetic defects and other incurable conditions taking them for treatments.

“Everybody was desperate,” said Dierkop, 66, who lives in Contra Costa County.

Rader said his sales representatives explain to prospective patients that he lost his license for standing up to the medical establishment. The board’s action has had little effect on his business, he said.

“Very few people don’t come because of that,” he said.

Twitter: @AlanZarembo

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.