What all those dead trees mean for the Sierra Nevada

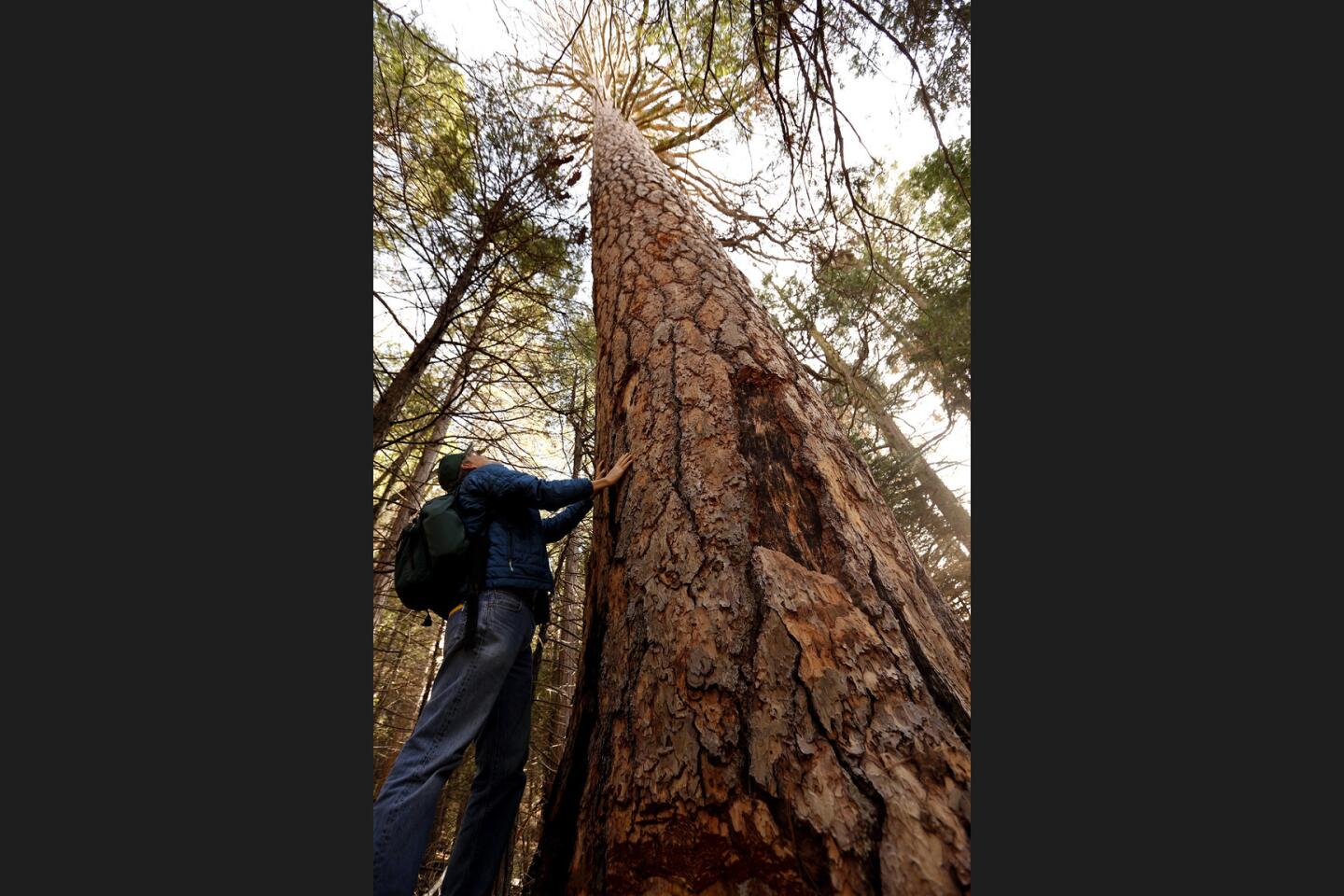

Reporting from SEQUOIA NATIONAL PARK, Calif. — The ponderosa pine had taken root decades before the Revolutionary War, making a stately stand on this western Sierra Nevada slope for some 300 years, Nate Stephenson figures.

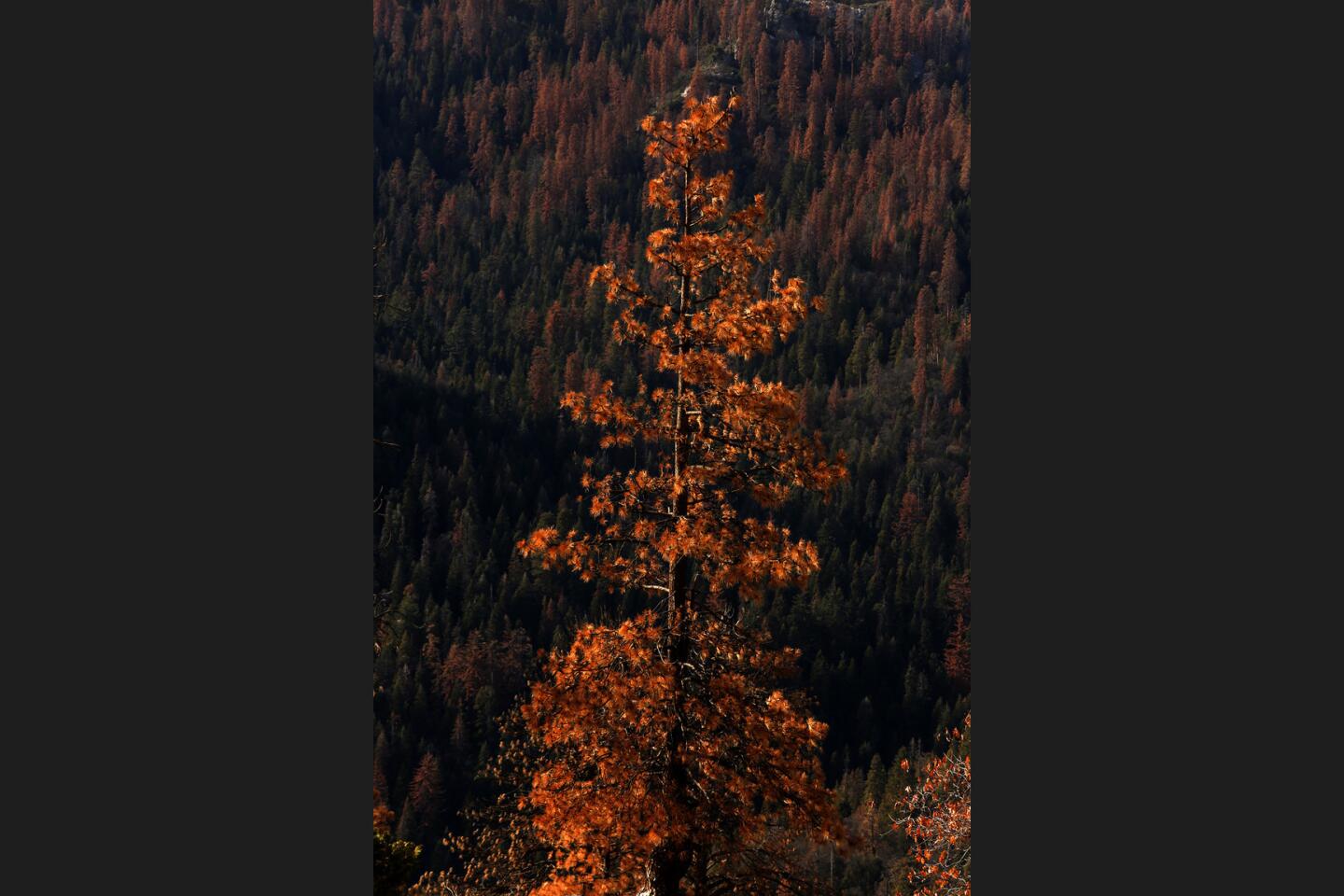

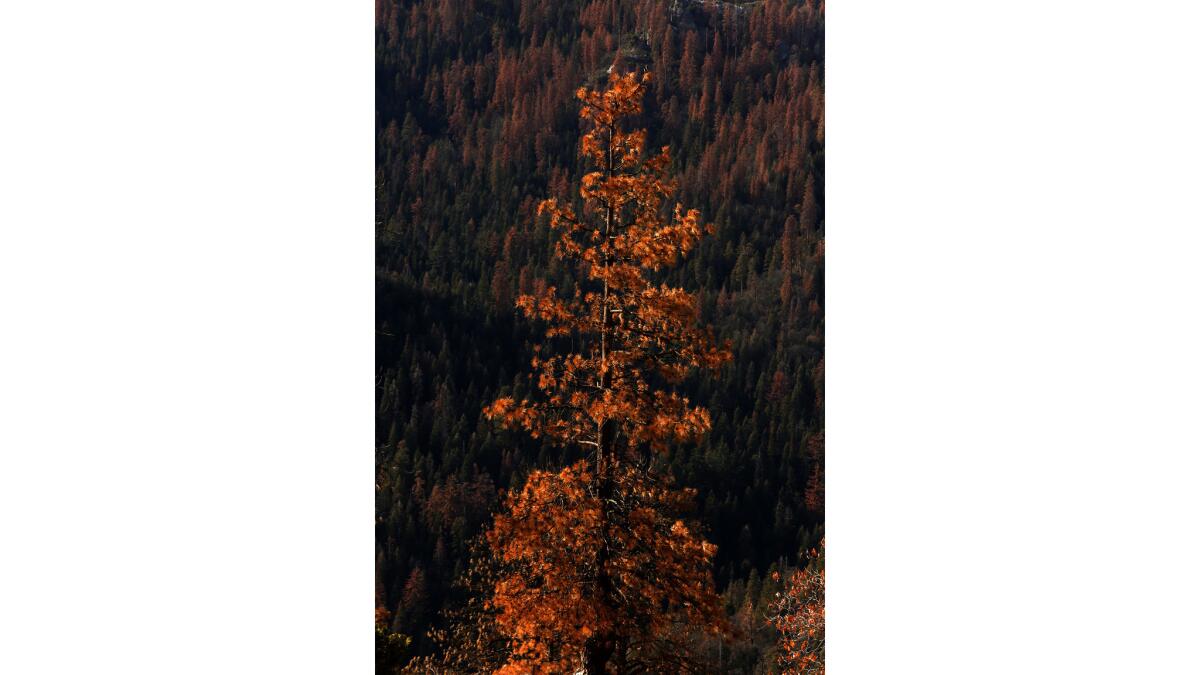

Then came the beetle blitzkrieg. Now the tree is a dab in the gray and rusty death stain smeared across the mountain range.

At the base of its massive trunk, a piece of bark has been cut off, revealing an etched swirl of insect trails. Higher up, naked branches reach out, as if from a many-armed scarecrow.

“This was alive until the drought killed it,” Stephenson says mournfully.

The U.S. Forest Service estimates that since 2010, more than 102 million drought-stressed and beetle-ravaged trees have died across 7.7 million acres of California forest. More than half of those died last year alone.

Exacerbated by anti-wildfire policies that produced a crowded forest more vulnerable to drought, the massive dieback is unprecedented in the recorded history of the Sierra.

The beetle epidemic is transforming the 4,500-foot to 6,000-foot elevation band of the central and southern range for decades to come, if not permanently. The sheer scale of mortality means that outside of developed areas, it’s likely that most of the tree corpses will be left to topple over.

It will takes centuries to replace the legions of majestic old pines that have succumbed — if that is even possible in a warmer future that promises to alter the forest in ways ecologists can only guess.

“We don’t know under the new conditions what things will do well,” says Christy Brigham, the top scientist and acting superintendent of Sequoia and Kings Canyon national parks.

But she’s pretty sure of one thing: The western Sierra pine forest as it was 100 years ago is not coming back.

Research ecologist Nathan L. Stephenson looks over a dead incense cedar tree in a plot of land that ecologists have been studying since 1992 in the Sequoia National Park.

“The world has changed…” Brigham says. “We’re never going to be able to get back to where we were before.”

::

When the first big patches of forest turned a fatal orange in 2015, “We were agog,” says Stephenson, a federal research ecologist who has worked in Sequoia National Park for nearly four decades. “It was hard to get over.”

Now he’s used to it.

And he finds comfort in a simple observation: “Most of the forest is still there.”

Higher elevations have largely escaped the beetle damage. Even in heavily infested areas, there is a mosaic of the living and the dead — patches of green and burnt sienna that from a distance suggest autumn in New England.

If a tree dies, we do an autopsy.

— Adrian Das, ecologist with the U.S. Geological Survey

The big ponderosa is in a research plot known as “BBB,” which scientists have monitored since 1992. Oak leaves crunch underfoot as Stephenson and his colleague, ecologist Adrian Das, walk through the stand of pines, fir, oaks and incense cedars marked with metal identity tags.

“If a tree dies, we do an autopsy. We look for bugs, we look for fungus,” says Das, who like Stephenson, works for the U.S. Geological Survey.

The pine’s killers left plenty of clues. Western pine beetles’ squiggles mar the tan inner bark, or phloem, where the dark brown females had tunneled and laid their eggs.

After hatching, the white, legless larvae ate their way into the middle bark, carving up the tree’s circulation system and cutting off the vital flow of water and nutrients.

The western pine beetle is just one of a number of native bark beetle species whose populations can explode when there is a bounty of easy pickings, such as during California’s protracted drought.

Thirsty trees are too stressed to kick out the rice-sized killers with secretions of pitch. When beetles find a good target, they send out chemical signals that act like a dinner bell, calling their kin for mass attacks. As many as 25,000 western pine beetles can infest a single large ponderosa.

Some people think some of these trees are coming back to life. They’re not.

— Chris Fettig, U.S. Forest Service research entomologist

Within a few weeks of the onslaught, the tree is dead. But it can take months for the needles to fade.

“Some people think some of these trees are coming back to life. They’re not,” said Chris Fettig, a Forest Service research entomologist.

Overall, about a fifth of the trees have died in the ponderosa pine and mixed conifer belt of the park, according to Stephenson and Das. Even after this winter’s parade of Sierra storms, the deaths will continue, since it takes about a year for trees to recover from prolonged water deprivation and regain their defenses.

None of the species that grow in that zone — typically ponderosa and sugar pines, incense cedar, white fir and black oak — have been immune to the dieback. Although mature giant sequoias have showed signs of stress, they appear to be pulling through the drought, perhaps because they grow in moister forest areas.

It’s the fine old pines that have suffered the most.

Stephenson’s sampling indicates that in the park areas of greatest mortality, about 50% to 70% of big ponderosa and sugar pines have died, compared with 20% to 25% of large white firs and less than 10% of incense cedars. (The cedars don’t have a major beetle predator.)

Stephenson, 59, has wandered the Sierra since he was a child backpacking with his parents. The landscape is like a beloved friend.

“What is heartbreaking is what’s really died off in droves are the big pines, a couple feet in diameter or more,” he says. “Pines that are hundreds of years old.”

Western pine beetles — which, along with mountain pine beetles, attack ponderosas — favor large-diameter trees. A big tree also needs more water and has to work harder to distribute it, making it more vulnerable to severe drought.

The world has changed…. We’re never going to be able to get back to where we were before.

— Christy Brigham, the top scientist and acting superintendent of Sequoia and Kings Canyon national parks

::

Nature is not the only culprit. Humans helped set the destruction in motion.

“We’ve produced a forest which basically has too many straws in the ground trying to draw a very limited amount of water,” says Malcolm North, a Forest Service research ecologist.

The federal government’s 20th century policy of putting out forest fires broke the cycle of frequent, low-intensity burns that had naturally maintained relatively open pine stands on the Sierra’s western slopes. Heavy logging and replanting in national forests after World War II led to crowded regrowth that never burned.

If wildfire had not been banished, North says, “we would not be seeing nearly so much mortality…. The thing that is really driving [it] is the high density, and the high density really results from fire suppression.”

If there is a silver lining in the staggering tree death, it’s that the survivors will have less competition. “If we go back to nondrought conditions, the remaining trees will be better off,” Stephenson says.

The bounty of bugs and ghostly trees is also a boon to cavity nesting birds and woodpeckers.

But from an ecosystem standpoint, many of the wrong trees have died — giant pines that are fire-resistant and provide a kitchen and bedroom for rare wildlife such as the Pacific fisher and spotted owl.

Getting rid of the massive amounts of dead trees in California has become both a problem and an opportunity.

::

In the Sierra National Forest northwest of the park, Forest Service ecologist Marc Meyer scans the fresh stumps of pines scattered across a picnic area at Bass Lake. The remaining live trees are mostly incense cedar and black oak.

“I have to wonder if we’re going to see a shift to a forest more dominated by oaks or a combination of oaks and conifers,” he says.

Downed logs, mounds of chipped trees and raw stumps — some of them huge — dot the lake’s misty rim on a winter day. Across the water, the forest is mostly a mortal reddish-brown, promising a depressing lake view for years, if not decades, to come.

“As ecologists, we’re struggling,” Meyer says. What restoration steps to recommend when future conditions are so uncertain? What kind of forest to aim for when the past is no longer a valid guide?

For much of the blighted zone, the question may be purely academic. The Forest Service is felling hundreds of thousands of dead trees next to roads and around developed areas for public safety reasons. So far the agency says it has treated 18,000 acres and is working on another 50,000 acres.

But there is a limited market for the salvage wood and a limited Forest Service budget for tree removal.

“There are massive areas in the landscape that you will just never get to because the economics don’t work out and the mill capacity isn’t there and the wood doesn’t have much value,” North says. “Most of those trees are just going to be there and fall over.”

Just how great a wildfire hazard that presents is complicated — and debated. A 2015 University of Colorado study of western pine forests with extensive beetle-related mortality concluded those regions have not burned more than healthy forests. And a study of the 2003 wildfires that tore through beetle-ravaged parts of the San Bernardino Mountains found those patches did not burn more severely than stands of live trees.

But generally speaking, fire scientists say the threat of a wildfire racing through treetops increases when dead needles remain on trees. Once they drop, that risk goes way down.

Skip forward 15 or 20 years, and fallen limbs and trunks pile up. That, warns UC Berkeley fire scientist Scott Stephens, turns the forest floor into a tangled mass of fuel. “Then we get lightning … and bang,” he says.

To lessen the fuel build-up, Stephens says federal land managers should conduct prescribed burns in hard-hit areas.

“In two, maybe four years, when all those needles are on the ground and before the big stuff hits the ground, I think you have to start burning in earnest,” he says. “I just don’t know what else to do.”

At this point, Forest Service managers say they are too occupied with developed areas to know what they will — or can — do on the broader landscape.

Options include prescribed burning and harvesting dead trees to feed biomass energy plants, says Scott Tangenberg, acting supervisor of the Stanislaus National Forest. But traditional logging, he adds, “is certainly an unlikely tool for us.”

Stephenson and Das spread out their lunches on Beetle Rock, a large granite outcropping that offers an expansive view from the Sierra slopes across the San Joaquin Valley to the coastal range. Below them is a rippling landscape that the past two years have radically altered.

“I’m not happy these trees are dead, but it’s fascinating,” Das says. “And when this mortality is done, there’s going to be a process where new things come in, and we don’t know what. It’s the beginning of something.”

Twitter: @boxall

ALSO

Brutal winter in Western U.S. has been terrible for animals

The 102 million dead trees in California’s forests are turning tree cutters into millionaires

January storms erase part of California’s snowpack deficit

257 drought maps show California’s deep drought and current recovery

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.