Santa Barbara oil pipeline leak rekindles memories of 1969 disaster

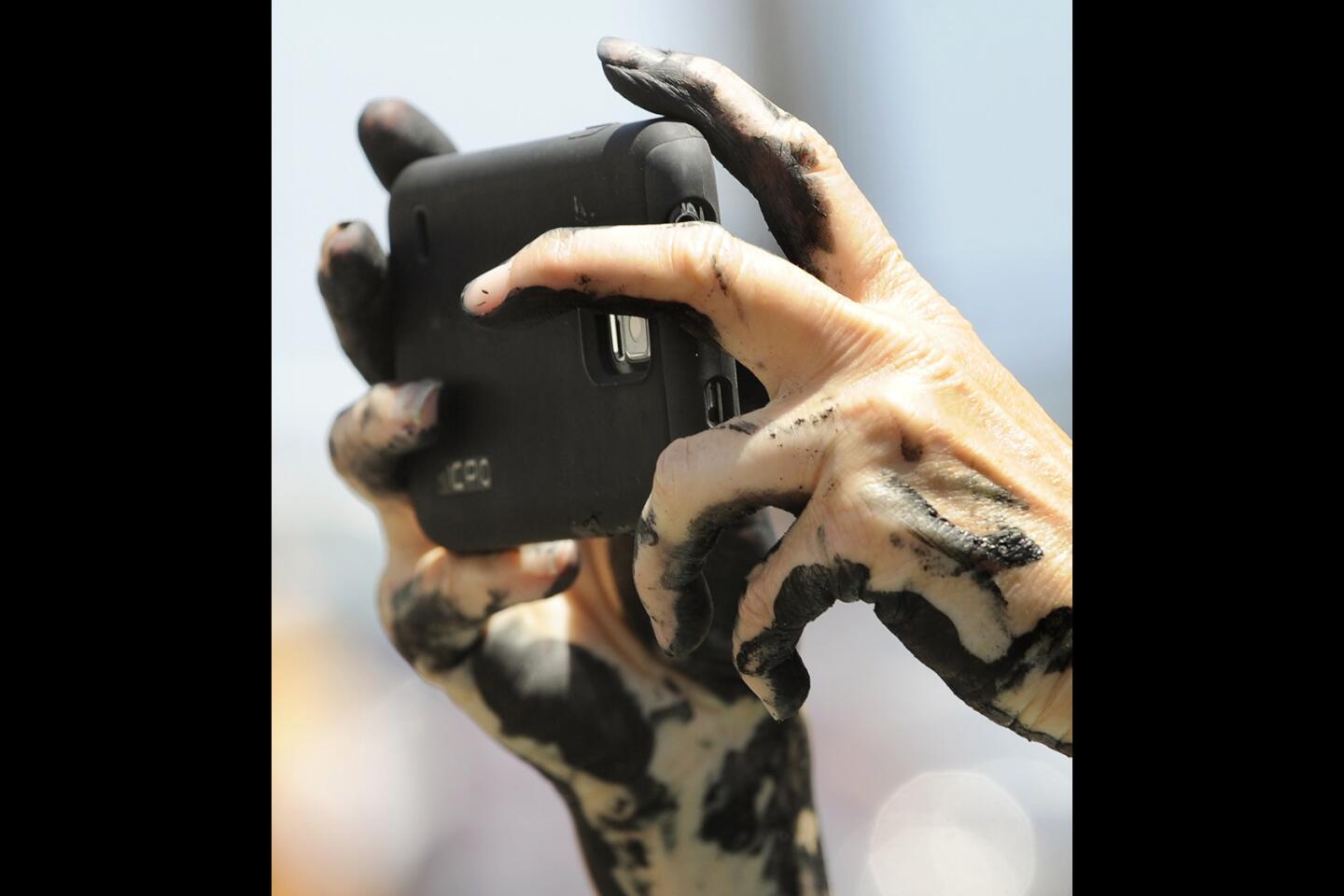

REFUGIO STATE BEACH, Calif. — It was a scene that generations of people on the Santa Barbara coast have dreaded: Cleanup workers in white protective suits combing tar-splattered beaches, hoping to contain the damage from a crude oil spill.

Nearly 50 years ago, a blowout on an offshore oil platform spewed more than 3 million gallons of oil into the Santa Barbara Channel and devastated the coastline, killing thousands of seabirds and galvanizing the U.S. environmental movement.

The spill that occurred Tuesday when a pipeline ruptured near U.S. 101 was far smaller — up to 105,000 gallons. But the incident gave rise to similar anger and frustration on the part of residents and environmentalists who have long feared a repeat of the 1969 disaster along the same sensitive coastline.

Santa Barbara County Supervisor Salud Carbajal, standing above a pile of blackened, oil-covered rocks at Refugio State Beach, said that the spill “reminds us of the perils this industry has.”

On Wednesday, the U.S. Coast Guard deployed half a dozen vessels to skim oil from the water and contain it with booms as crews of cleanup workers removed tar and oil from sand and rocks on the shoreline and shoveled mud into clear plastic bags.

Federal authorities said the 24-inch pipeline leaked for several hours after it ruptured near Refugio State Beach. Crews stopped the leak by 3 p.m., Coast Guard Petty Officer Andrea Anderson said.

The oil flowed down a culvert and into the ocean, and by Wednesday morning had formed two slicks totaling a combined nine miles in length.

Authorities estimated that it could take at least three days to clean up the spill.

The rupture occurred on an 11-mile pipe owned by Houston-based Plains All American Pipeline that carries crude from a storage tank in Las Flores to a facility in Gaviota. The pipeline is part of a larger oil transport network that is centered in Kern County and carries oil to refineries throughout California.

The pipeline was designed to carry about 150,000 barrels of oil per day, according to company officials.

The company said its estimate of 105,000 gallons spilled is a worst-case scenario based on the line’s elevation and flow rate, which averages about 50,400 gallons an hour. Of that, about 21,000 gallons reached the ocean, but both figures are under investigation, according to a statement from the company and state and federal officials. Investigators won’t find a cause for the rupture until they excavate the line, which was installed in 1987. An employee noticed problems and shut the line down about 11:30 a.m. Tuesday, the statement said.

That pipeline had not ruptured before, the company said. An inspection of the line using an internal tool was completed a few weeks ago but results hadn’t come back before Tuesday’s incident, the company said.

Michelle Rogow, a site manager with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, said the pipeline had been regulated by the State Fire Marshal until two years ago, when jurisdiction was transferred to the Department of Transportation.

Below the spill site, just west of Refugio State Beach, a wide, black path stained the landscape of eucalyptus trees and shrubs. The oil apparently flowed through a storm drain that runs under U.S. 101 and train tracks, and into the ocean.

Officials were investigating reports of dead and live birds covered in oil, but the state Department of Fish and Wildlife did not have an official count of the animals affected. The agency deployed teams on shore — and one in a boat — to look for birds, marine mammals and other wildlife harmed by the spill.

But some of the victims of the spill were becoming apparent.

Near the spill site, Reeve Woolpert, 69, of Summerland found a brown pelican covered in oil and alerted state Fish and Wildlife and state parks officials. Nobody came for several hours, Woolpert said, so he wrapped the bird in his T-shirt and carried it up the bluffs to a state Fish and Wildlife worker, who took it away in a cardboard box.

“I said this bird wants to live, it’s a fighter,” Woolpert recalled.

Darren Palmer, district manager for Plains, said: “We’re sorry that this accidental release has happened.” The company had dedicated about 130 workers to the cleanup. Patriot Environmental Services, the same firm that did Gulf of Mexico cleanup after the 2010 BP oil spill, was brought in to handle the task.

Linda Krop, chief counsel for the Santa Barbara-based Environmental Defense Center, said the incident was a stark reminder of the risks that remain even decades after the 1969 oil spill, “which was so massive and so devastating that a lot of people thought that there wouldn’t be any more offshore oil development here.”

“The lesson is that no matter how strict the regulations become and how advanced the technology becomes, we’re going to continue to have oil spills,” Krop said.

Krop questioned why the pipeline did not shut off automatically and whether an earlier, more aggressive response to the spill could have kept more of the crude out of the ocean.

She said she worried about how far the slick would spread through the Santa Barbara Channel, which she called “one of the most biologically rich places on the planet” for its migrating whales and rare and endangered seabirds. “It’s a very, very sensitive, important place and we don’t know what the eventual harm will be.”

Fishing and shellfish harvesting were closed for one mile on either side of Refugio State Beach, a popular coastal campsite. El Capitan State Beach was also closed. Authorities said both would be shut through the Memorial Day weekend.

The Santa Barbara County district attorney’s office and the attorney general’s office are also investigating the spill, officials said.

At a rest area along U.S. 101, travelers and residents stopped to watch the cleanup effort as helicopters buzzed overhead and cleanup boats corralled slimy crude in long yellow booms, Angel Waters, 34, of Silver Lake, who had been camping at Refugio earlier in the week, shook her head.

“We were watching whales and dolphins, smelling the sea and thinking how beautiful it was,” she said. “Now this.”

Robert Sears, 57, of Fairfax, Calif., said he felt a little guilty about his gas-guzzling SUV as he watched boats skim crude from the ocean surface.

“I came here to watch whales,” said Sears, a robotics engineer. “What I see instead are containment booms. What can I say, we’re really ruining our world.”

from Los Angeles. Times staff writers Steve Chawkins in Santa Barbara and Joseph Serna and Matt Hamilton in Los Angeles contributed to this report.

Panzar and Morin reported from Santa Barbara County, Barboza from Los Angeles. Times staff writers Steve Chawkins in Santa Barbara and Joseph Serna and Matt Hamilton in Los Angeles contributed to this report.

Twitter: @jpanzar

Twitter: @montemorin

Twitter: @tonybarboza

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.