From the Archives: Police pullout, riot’s outbreak reconstructed

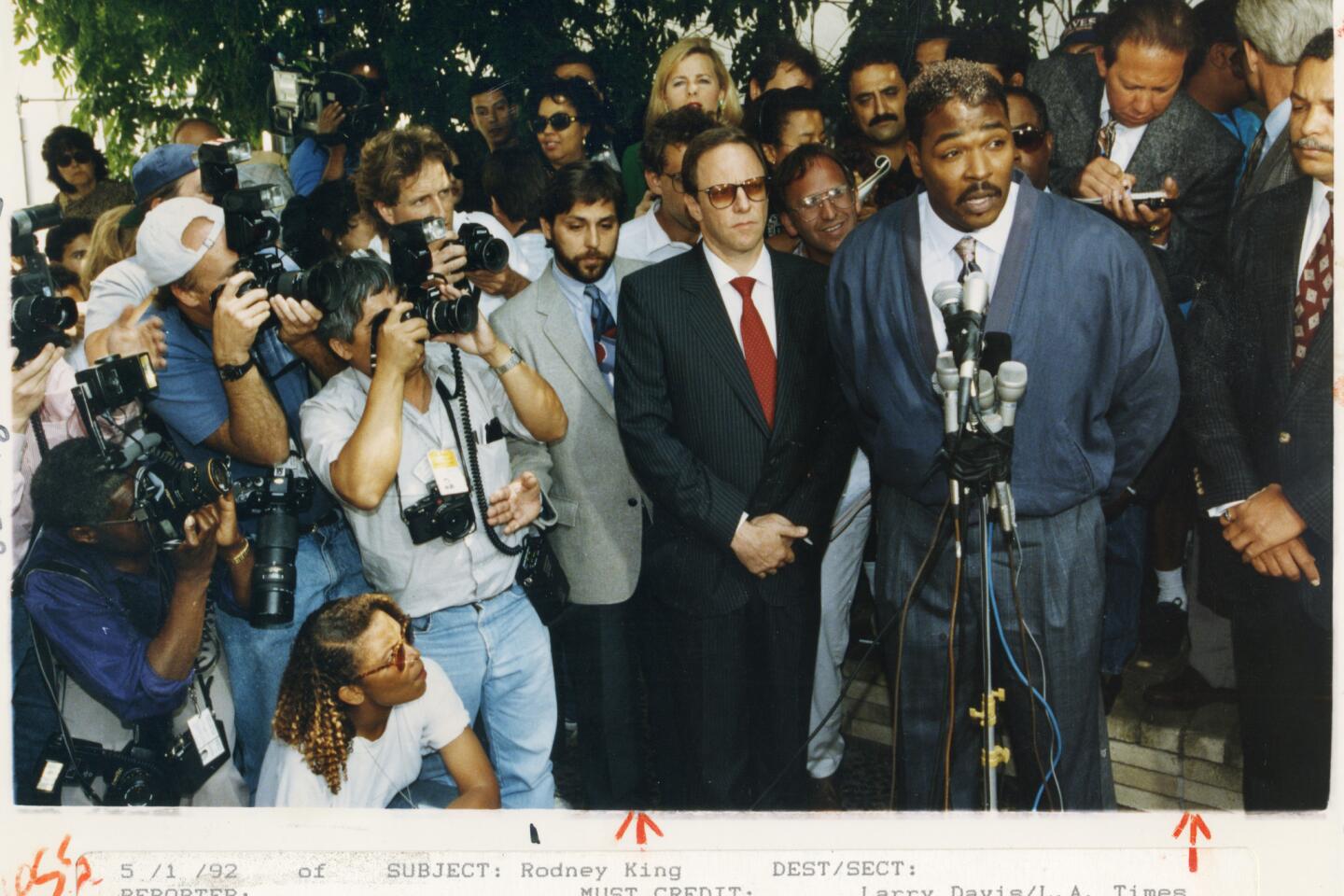

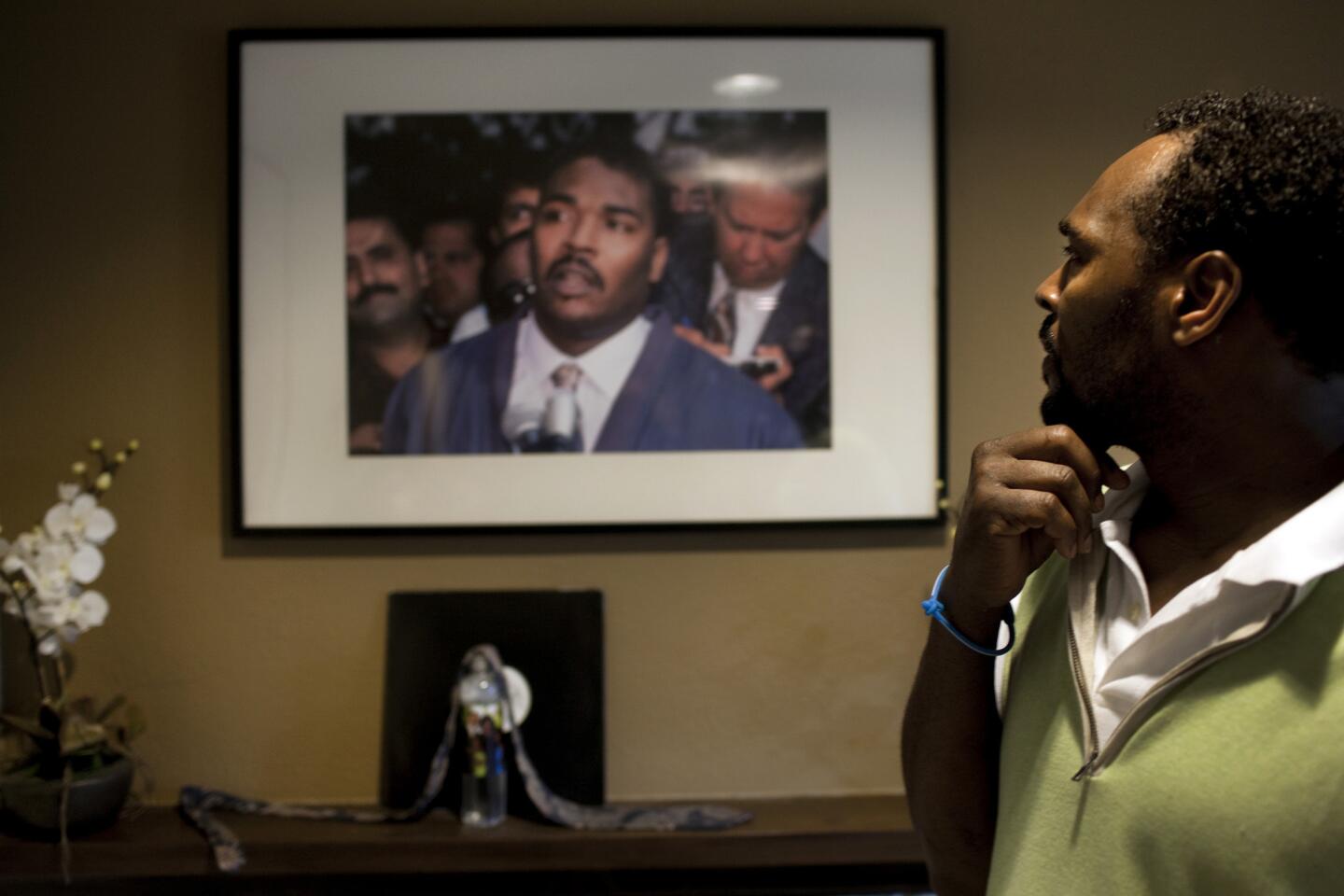

In the incident that appeared to trigger last week’s riots, at least 20 Los Angeles police officers backed down late last Wednesday afternoon in a tense confrontation with South Los Angeles gang members and other residents furious over the verdicts in the Rodney G. King case.

The officers fled when the encounter turned into a shoving match in front of a house at 71st Street and Normandie Avenue and one officer told his colleagues repeatedly: “It’s not worth it. Let’s go.” They did not return for hours and have refused to fully explain why.

After the officers’ departure, the crowd of perhaps 50 quickly surged one block south to the intersection of Normandie and Florence avenues and raged unchallenged for hours in a display of destruction.

Members of the crowd stoned Anglo and Latino motorists, pulled them out of cars and looted and torched stores, according to witnesses and an amateur videotape of many of the incidents made available to The Times on Monday.

Although much already has come to light about the violence that accompanied the not guilty verdicts, interviews with government and police officials, witnesses and the videotape provide the most detailed account to date of the embryonic stages of the riot that has claimed more than 55 lives.

The decisions to leave Florence and Normandie and not return as the disturbance intensified will be examined in detail by the Police Department, the Police Commissioner and, no doubt, many historians.

Cmdr. Robert Gil, the LAPD’s chief spokesman, said: “No one person knows the whole story of what happened that (Wednesday) night . . . we are looking into the matter now.”

Police Chief Daryl F. Gates on Monday issued a general defense of his conduct in planning for and coping with the disturbance. “My judgment was not wrong,” said Gates. “We were properly deployed.”

There was discord, however, between Gates and one of his top commanders about the best way to plan for the possibility of the riot, according to the department’s second-ranking officer.

The amateur videotape, shot from ground level, adds to horrific video images of activities on that corner that were broadcast live by a television news helicopter that circled overhead. The amateur videotape, which began before the live broadcasts, shows clearly that significant numbers of police were present but left.

As officers got in their cars and sped off, the crowd at first seemed about ready to disperse. But suddenly, for reasons that are not clear, the largely black crowd got a new sense of purpose--the venting of racial hatred.

In the videotape, someone picked up a metal sandwich board advertising Marlboros and slammed it through the rear window of a Volvo heading west on Florence. The riot was on.

Shouting epithets at Anglos, Latinos and Asian-Americans, members of the crowd vented their anger in the name of vengeance for Rodney G. King.

“F--- ya’ll!” shouted a woman at some badly beaten motorists who had been pulled form their vehicles. “F--- ya’ll! Ya’ll did old Rodney King wrong! Ya’ll going to pay!”

“No pity for the white man,” said a man as he looked at the bloodied and kneeling Anglo who had been pulled from his white panel truck. “That’s how Rodney King felt, white boy.”

Some officers who were ordered by their supervisors to leave the scene said they also were ordered not to return to the intersection. Instead, they said they were sent to a command post at an RTD bus depot several miles away where they waited hours for instructions.

The amateur videotape shows at least two marked police cars barreling through the intersection during the riot, sirens blaring, without stopping.

Police say they fled the corner that became the flash-point of the worst riot in the city’s history because they were overwhelmed a few minutes before 6 p.m. But they have yet to explain fully why they did not return. The morning after the riot began, Gates said it took time to organize the officers for riot conditions and once they were organized, there were higher priorities such as protecting firefighters.

Although the police retreat may have helped pull the trigger on the riot, the gun was clearly loaded hours earlier when a Simi Valley jury with no black members returned its verdicts against the four white LAPD officers.

In offices at City Hall and police headquarters as well as in the homes of residents of the Florence and Normandie area, including some Eight-Tray Gangster Crips, television sets were tuned to the verdict, which turned heads in disbelief.

After watching a report on the verdict alone in his large third-floor office at City Hall, Mayor Tom Bradley told aides: “I’m stunned.”

His aides and high-ranking police officials had expected convictions or at least a mixed verdict.

“Nobody, nobody expected this extreme a verdict,” said Police Commission President Stanley K. Sheinbaum.

Some members of the Eight-Tray Gangster Crips street gang and others say they gathered in an abandoned house on 71st Street just around the corner from Florence and Normandie to commiserate and figure out what to do.

According to people who say they were there, a respected figure known on the streets as C-Balll, an “O.G.” or original gangster, suggested that the group take a peaceful protest to Westwood or Simi Valley.

But as the group was discussing that idea, “some of our homies” went to a neighborhood liquor store where, according to another O.G. known as L’il Monster, they got into a dispute with the son of the Korean owner.

Others in the neighborhood said there were tensions between the mostly black customers and the Koreans.

“I don’t know if someone tried to steal something or what,” said L’il Monster, who declined to give his true name, “but the store owner(‘s son) was assaulted. . . . I think he was hit in the head with a 40-ounce bottle of Old English.”

The police responded to the area shortly thereafter but accounts differ as to whether it was in response to this disturbance or another by the same group of people gathered two blocks away, near the corner of 71st and Normandie.

Many of those in the gathering were drunk and angry, according to one neighborhood resident who declined to give his name.

Two 77th Division police officers said they responded to a disturbance call in the vicinity that consisted of people yelling at passing cars and the police. Some officers left but returned moments later when a colleague radioed that he needed assistance.

“There was about 100 of them and 30 of us,” said Officer Rashad Sharif.

“The crowd was huge and officers were taking bottles” thrown by residents, said another patrol officer who demanded anonymity because of orders not to grant interviews about the incident. “We were outnumbered. We didn’t have enough guys to watch our back.”

When officers made two arrests, the crowd became inflamed, he said. “It was chaos. (Officers) were trying to stop them. They were coming toward us.”

One of the two people arrested and taken away was said to be C-Balll the O.G. whose associates said had wanted a peaceful demonstration. C-Balll was booked on suspicion of assault with a deadly weapon on a police officer, although some neighborhood residents said he had done nothing.

“They pulled the one person away who could control it,” said neighborhood resident Donnell Alexander, a medical technician who had come to C-Balll’s gathering at the house after work and witnessed much of the evening’s destruction.

On the amateur videotape, the police are shown holding their ground, arm in arm, batons at the ready, as members of an increasingly angry, crowd shout and press in on them.

All of a sudden, some officers can be seen starting to run, while a voice from the crowd says, “They got their m----- f---- riot gear on.”

Only one officer can be seen on the tape wearing a riot helmet.

Then the camera pans erratically to a scene of pushing and shoving between police and some black men on the sidewalk of a nearby house.

A voice, sounding like that of an officer over a bullhorn, can be heard saying, repeatedly, “It’s not worth it. Let’s go.”

“If we would have stood our ground, there would have been a shooting, and people would have gotten killed without a doubt,” said the patrol officer who demanded anonymity.

After the retreat, this officer said, he heard an order over the police radio: “Do not go through Normandie and Florence.”

About 10 minutes later, two police cars, sirens wailing, can be seen on the videotape driving through the intersection without stopping to try to halt what by then had turned into a rock-throwing mob.

The police went to a command post that had been set up in the RTD bus depot at 54th Street and Arlington Avenue. Police officials declined to say when this had been set up.

“We sat there and waited for assignments” for a couple of hours, said the 77th Division officer. “We wanted to go out in numbers.”

He said that, by the time they were redeployed, it was to escort firetrucks.

Gates has explained the police behavior this way: “There were more people there than the officers could handle. We had to back off, and wait for additional resources. . . . By that time the resources were drained off” by raging fires.

Gates was at Parker Center preparing to leave at about 6:30 p.m. Wednesday when the undeterred crowd at Florence and Normandie was pelting cars with rocks and bottles looted from a liquor store on the corner. A reporter who encountered the chief as he was leaving police headquarters asked Gates about police response at the intersection. Speaking generally, Gates assured the reporter that his officers were going to handle any incidents that developed in a calm and mature fashion.

Moments later, as Gates pulled out of the parking garage, Police Commission President Sheinbaum pulled in.

He asked Gates where he was going. Sheinbaum said the chief gave no answer. Gates was on his way to a Brentwood fund-raiser to oppose a package of proposed charter amendment changes to make the police chief more accountable to elected officials.

The day before, Gates had assured members of the Police Commission that the department had adequate contingency plans. The commission sought no details, and department officials have been unwilling to discuss the plans.

However, there was some disagreement between Gates and other top police officials about the best way to prepare, said Assistant Chief David D. Dotson, the department’s second-ranking official.

Dotson said that at staff meetings during the King trial, Deputy Chief Matthew Hunt, whose area of responsibility includes South Los Angeles, urged that “we ought to be doing something in regard to being ready.” Hunt was particularly concerned, Dotson said, in light of a community-based policing experiment that had taken three of his four stations out of his command and made them directly accountable to the chief.

“There was some discussion that we needed to clarify the organizational responsibilities and command lines so that if something untoward did occur, it would be very clear who was in charge of whom,” Dotson said. “His response from the chief was that this will take care of itself when the time comes--sort of a dismissal of the whole thing as a real serious consideration. It got to the point where it was somewhat embarrassing because Hunt kept hammering and the chief kept dismissing.”

Hunt refused to be interviewed.

In any event, during the hours when the riot was beginning to spread, there is evidence that some department officials had no sense of the magnitude of events that were beginning to unfold on the streets.

They had turned on the phones and television sets at the city’s Emergency Operations Center in a sub-basement of City Hall East and left a police captain in charge, Dotson said. Then, some of these top officials left for the day.

At Florence and Normandie, child-care worker Alphonso Hawkins said people in the crowd were “throwing bricks and bottles at white people” driving by. Those attacked, he said, were being taken by surprise.

But when a sand-and-gravel truck appeared in the distance, heading west on Florence toward the intersection, Hawkins said some people on the sidewalk waved their arms to try to warn the driver off. He paid no attention to them. “When he got up to the intersection they busted the glass out, dragged him out of the truck and whupped him,” Hawkins said.

Assistant Chief Dotson said he got home just in time to see live television helicopter pictures of that driver, Reginald O. Denny, being savagely beaten.

Mayoral press secretary Bill Chandler saw the same pictures at his office in City Hall. He quickly telephoned another aide to Mayor Tom Bradley who had accompanied the mayor to a long-planned rally at the First African Methodist Church where civil leaders were appealing for calm in the African-American community.

Chandler told mayor aide Phil Depoian that television was showing a man being beaten at Florence and Normandie and there was no police response. Depoian went to Deputy Chief Hunt and said he told Hunt of the trouble. He said that Hunt immediately called the 77th Division station and ordered police units sent to the intersection.

After the call, Hunt left, Depoian recalled.

The mayor, who was sitting on the stage waiting to speak, was told of the unfolding tragedy and cut short his appearance and headed back to City Hall.

About 7:15 p.m., as Gates was nearing the fund-raiser in the Mandeville Canyon section of Brentwood, Depoian said he called Hunt at a command post that had been set up at 54th Street and Arlington.

“Phil, it’s getting ugly,” Depoian recalled Hunt as having said. “I think we’re going to need the National Guard.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.