‘Don’t call me Ms. ... it means misery’: Phyllis Schlafly, anti-feminist and conservative activist, dies at 92

In the 10-year battle over the Equal Rights Amendment in the 1970s, there was no more formidable opponent than Phyllis Schlafly.

Feminist leader Betty Friedan famously hissed at her during a debate, “I’d like to burn you at the stake.” Chicago columnist Mike Royko dubbed her “a national nag.” And a political activist smashed a pie in her face, injuring her eye.

Through it all, Schlafly — known as “the first lady of anti-feminism” — remained impeccably groomed and seemingly unflappable.

“You have to keep your sense of humor,” she told The Times in 1996.

Schlafly, the political activist who galvanized grassroots conservatives to help defeat the ERA and effectively push the Republican party to the right in ensuing decades, died Monday at her home in St. Louis. She was 92. A spokesman for the Eagle Forum, the political organization she formed in that city, said she died in the presence of family.

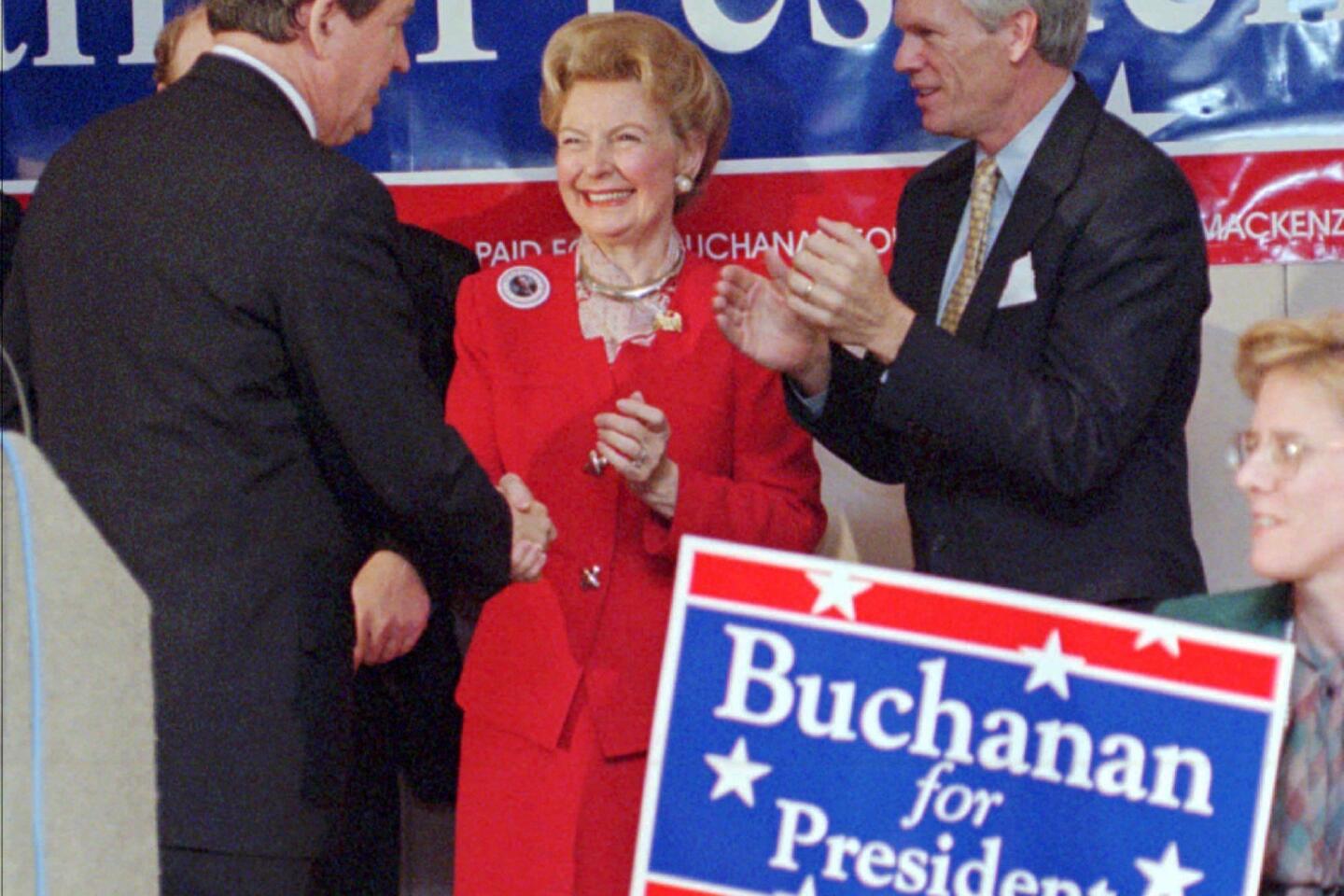

Schlafly had remained deeply involved in politics. She was on the floor of the Republican National Convention in Cleveland, her 12th straight, to back Donald Trump. Months earlier, she introduced him at a campaign appearance in St. Louis, calling his candidacy a “grass-roots uprising.”

“We’ve been following the losers for so long — now we’ve got a guy who’s going to lead us to victory,” she said.

By then Schlafly had been a standard bearer for the conservative branch of the Republican Party for decades, writing the influential book “A Choice Not an Echo” to help Barry Goldwater secure his party’s presidential nomination in 1964.

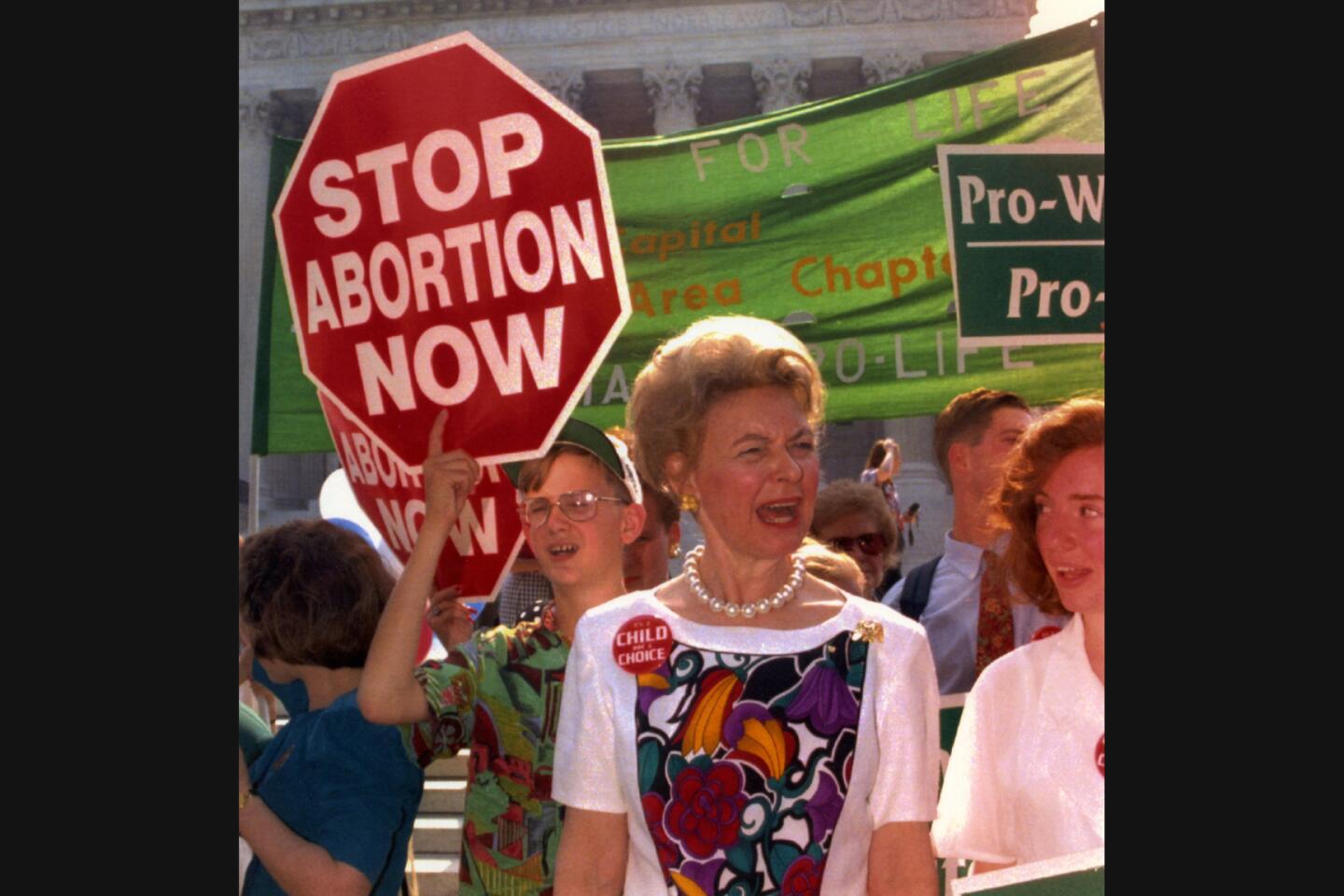

Beginning in 1972, she led opposition to the ERA — a 52-word constitutional measure that guaranteed equal rights under the law regardless of gender — arguing that it would mark the end of the traditional family.

“She was an important figure who was the first to plug in to the power of the female conservative vote in modern times,” said Donald Critchlow, author of the 2005 political biography “Phyllis Schlafly and Grassroots Conservatism: A Woman’s Crusade.”

“Her importance wasn’t fully seen until the ascendancy of the right that began with the election of Ronald Reagan as president,” he said.

The National Organization for Women, which made the amendment central to its mission after it formed in 1966, had cast the ERA as a matter of economic equality.

Schlafly’s entrance into the fight focused the debate on the changing role of women in society.

Her army of volunteers brimmed with stay-at-home mothers, and she contended that the amendment would deprive a woman of the fundamental right to stay home and care for her children.

“Phyllis Schlafly courageously and single-handedly took on the issue of the Equal Rights Amendment when no one else in the country was opposing it,” James C. Dobson, chairman and founder of Focus on the Family, told the St. Louis Dispatch in 2005. “In so doing, she essentially launched the pro-family, pro-life movement.”

Her calmly expressed, unshakable conviction that the amendment was a threat to a woman’s financial security and traditional motherhood drove pro-ERA audiences crazy.

“The only way to debate Phyllis Schlafly is to jump up and down and shout ‘Liar, liar, liar!’” one feminist told Newsweek in 1977. (The magazine branded her “the first lady of anti-feminism” in 1979.)

When Schlafly and her troops entered the fray, 30 states had already ratified the ERA. Within a year, the amendment — first introduced in Congress in 1923 — started losing steam. It ended up three states short of the 38 needed for ratification and was defeated in 1982.

“Would the ERA have passed without Phyllis? That’s the $64,000 question,” Karen DeCrow, president of NOW in the mid-1970s who debated Schlafly at least 50 times, told The Times in 2005. “Bing-bing-bing, the states were ratifying it before she got involved. If she hadn’t, then bing-bing-bing, we might have had three more states.”

By the turn of the century, some feminists and historians said they felt history had passed Schlafly by. Many of the changes contained in the ERA happened over time anyway. Her emotionally charged argument against the amendment included warnings that it would force women to serve in combat zones, cause unisex restrooms to proliferate and allow gays to marry.

Schlafly believed women who blamed sexism for their failures were just looking for excuses.

“The claim that American women are downtrodden and unfairly treated is the fraud of the century,” she wrote in her 1977 book “The Power of the Positive Woman.” (“Don’t call me Ms.,” she repeatedly said. “To me, it means misery.”)

“If you’re willing to work hard, there’s no barrier you can’t jump,” she said, offering herself as Exhibit A.

Critics said that though Schlafly presented herself as a traditional homemaker, she often traveled, had a full-time housekeeper and a personal assistant, and a resume that most feminists would envy.

“People quoted me for years for saying, ‘If I had a daughter I would want her to be a “housewife” just like Phyllis Schlafly.’ I still believe that,” said DeCrow.

Schlafly was credited with inspiring a new generation of conservative women, including author and columnist Ann Coulter, who wrote the foreword for Schlafly’s 2003 book, “Feminist Fantasies.”

Schlafly’s first brush with fame came in 1964 when 3 million copies of her self-published book “A Choice Not an Echo” were sold, mainly to Goldwater workers who bought in bulk.

Missouri delegate Phyllis Schlafly at the Republican National Convention in Cleveland in July. This year she released a book making the case for a Donald Trump presidency.

In the book, Schlafly claimed that Eastern internationalists — the Nelson Rockefeller wing of the party — had forced their candidates on the party for years.

“This was strong medicine, even for a campaign book intended to stir up the Republican grass roots,” Critchlow wrote, yet “it proved remarkably successful in its goal.”

Phyllis McAlpin Stewart was born Aug. 15, 1924, in St. Louis, the elder of two daughters of John and Odile Stewart. Her mother worked for 25 years as the head librarian at the St. Louis Art Museum.

After a year at Maryville College of the Sacred Heart in St. Louis, Schlafly transferred to Washington University, also in St. Louis, and paid for her education by testing rifles and machine guns on the night shift at a World War II munitions plant.

She earned her bachelor’s degree in political science in 1944 and received a master’s degree in government from Radcliffe College a year later.

In 1949, she married Fred Schlafly, a fellow Roman Catholic and conservative 15 years her senior. They were together until his death in 1993. The young couple moved to the industrial city of Alton, Ill., and she became a self-described homemaker.

When the first of her six children was a toddler, she plunged into an unsuccessful campaign for Congress, one of two, and became a fixture as a delegate and behind-the-scenes platform player at Republican national conventions.

In later years, Schlafly cited 1964, the year she turned 40 and wrote her first book, as the most productive of her life.

She began collaborating that year with Adm. Chester Ward on “The Gravediggers,” the first of five books they wrote on the Soviet military threat. (The partnership endured until Ward’s death in 1978.)

She also ran the Illinois Federation of Republican Women, successfully ran for vice president of the National Federation of Republican Women, won a contested race to be a delegate to the Republican National Convention, and made dozens of speeches for Goldwater. On Nov. 16, 1964 — 13 days after her candidate was crushed at the polls by President Lyndon Johnson, she gave birth to her last baby.

In “Phyllis Schlafly: The Sweetheart of the Silent Majority,” author Carol Felsenthal argued that Schlafly “was obviously ‘liberated’ decades before the word got hackneyed. She never, ever allowed her sex to stand between her and her goal. And that perhaps, is one reason for her unrelenting disdain for ‘libbers.’“

When Schlafly found her authority repeatedly challenged during ERA debates because she wasn’t a lawyer, she attended Washington University “in her spare time” and graduated with a law degree in 1978.

At the start of the ERA fight, she founded the St. Louis-based Eagle Forum, which became an influential conservative group that she ran with a firm hand. She took no salary.

At the 1992 GOP convention in Houston, Schlafly supported the party’s platform, which condemned same-sex marriage and gay civil rights. Soon after, a New York gay magazine outed her oldest child, John, then a 41-year-old lawyer who helped run the Eagle Forum.

“I love my son,” she told the New York Post in a reaction story at the time. “But all my children are adults and lead their own lives.”

Her children grew up to be achievers — three lawyers, an orthopedic surgeon, a mathematician and a businesswoman — and conservatives.

“I had six children,” she said in 2008, when she backed John McCain’s choice of Alaska Gov. Sarah Palin as a running mate. “I ran for Congress. An organized mother puts it all together. The time-management mother uses the older ones to help with the younger ones. You should read that old book ‘Cheaper by the Dozen.’”

Nelson is a former Times staff writer.

ALSO

Hugh O’Brian, actor who played Wyatt Earp, dies at 91

Analysis: In Pennsylvania and nationally, Trump’s problems with suburban voters blunt his ascent

Campaigns converge on Ohio: Trump meets voters; Clinton thinks she is ‘allergic’ to GOP nominee

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.