Though cancer may slow Najee Ali down, the L.A. activist keeps up the fight for justice through social media

Former Assembly Speaker Bob Hertzberg greets community activist Najee Ali at a coffeehouse in Los Angeles in 2005.

The family of the woman shot dead by police at an Inglewood street corner milled around in grief as TV cameras set up near a memorial of teddy bears and candles.

Then Najee Ali walked up to them, ready to perform an urban ritual he has presided over for about 20 years.

He greeted reporters by name and then huddled together the woman’s relatives like a quarterback about to call a play.

Mother and sister would address reporters, he said. Don’t yell for donations during the news conference. Punt any questions they didn’t feel comfortable answering to him.

“Trust me, if you listen to me everything will be fine,” he said before leading the group to a throng of television cameras.

Over two decades of activism, Ali, 53, has been a familiar face not only in Los Angeles’ black community, but on TV after events such as a controversial police shooting and gang violence. His outspokenness over the years toward police, politicians and others —– including calling the National Assn. for the Advancement of Colored People and other groups “outdated” — have amassed him a collection of friends and foes.

During an appearance on CNN, former L.A. Police Chief William J. Bratton called Ali “one of the biggest nitwits in Los Angeles.” Bratton, now New York’s police commissioner, later apologized. Rep. Maxine Waters (D-Los Angeles) took out a restraining order against Ali, after he sought one on her. They eventually made peace.

Ali’s personal history always made him vulnerable to criticism. He was a former gang member who used to be a crack addict on skid row. He served several stints in prison, including two years beginning in 2008 for bribing a witness in a criminal case involving his daughter.

“People who speak for the community should be held to a high standard of principle and integrity,” Lisa Collins, publisher of the monthly religious magazine L.A. Focus, said in a statement. “In the case of Mr. Ali, the record is clear and it includes convictions for bribery, perjury, felony hit and run, charges of intimidation and numerous run-ins with high-profile community representatives.”

To some people, Najee Ali was best at promoting Najee Ali. But to supporters, Ali was effective at keeping the spotlight on certain issues even after media interest began to fade.

“He’s an old-school, in-your-face activist,” said Kerman Maddox, a longtime friend and a political affairs consultant. “He’s not intimidated by politicians. In that regard, you have to respect the guy.”

Community activist Najee Ali, in the purple shirt, prays during a vigil in memory of Latasha Harlins, a teen who was fatally shot by South L.A. shop owner Soon Ja Du in 1991.

What Ali is almost incontrovertibly is a throwback to another era of activism in L.A., and arguably around the country. The rise of groups such as Black Lives Matters has removed the focus from individual, ordained leaders of the black community. In the second-largest city in the U.S., this has also coincided with the ascendance of women leading protest movements.

In this landscape, Ali is about to take a most unusual, but necessary, step: shrink from the limelight.

Two years ago doctors diagnosed him with Stage 3 lymphoma. Cancer. They told him he had to slow down. Soon, his own body was telling Ali the same.

“The wear and tear with chemotherapy is taking its toll,” he said while sipping a marsh green cold-pressed juice — part of his effort to live healthier.

“A protest or march has never solved a problem in the black community,” Ali said. “But it puts the issue out there and it keeps the conversation going on the issue until we can figure out how we can solve the problem.”

But activism takes physical exertion, and bouts of chemotherapy left him ragged. As he tried to recover from the treatments designed to keep him alive, he realized he didn’t always have to be on the ground to fight for social justice. He increasingly relied on his social media accounts, including Twitter and Facebook, to reach people with a click of a button. He also writes a weekly column in a local newspaper.

“My whole life has been one of evolving,” Ali said. “So it dawned on me, let this be an opportunity to rest and heal, but evolve and do something different.”

On an unseasonably warm day in February, his phone rang. The man on the other end told Ali that his mother was missing. She has Alzheimer’s disease, he said.

“I was going to ask if you could use your social media ... to get some extra eyes out there to locate her,” the man said.

“Text me a picture and her name along with other information and I will post it,” Ali replied.

“This is the day in the life of Najee Ali,” he said. “I get these phone calls all the time. ‘I need help. Can you do this and do that?’”

Ali’s travails, his trouble with the law, might have given his critics ammunition. But what has made him the target of criticism has bolstered his street cred.

Before he became Najee Ali, he was Ronald Todd Eskew. He was born to a mother who worked as a prostitute and an abusive father.

His mother died when he was age 12. Ali bounced from one relative to another until he went to live with his grandmother. Like many youngsters in his neighborhood, he joined a gang and dropped out of high school at 17. He was in and out of jail.

In 1990, while in jail for robbery, he read “The Autobiography of Malcolm X.” The story of a former drug addict, ex-con who converted to Islam and fought for black people’s rights resonated with Ali.

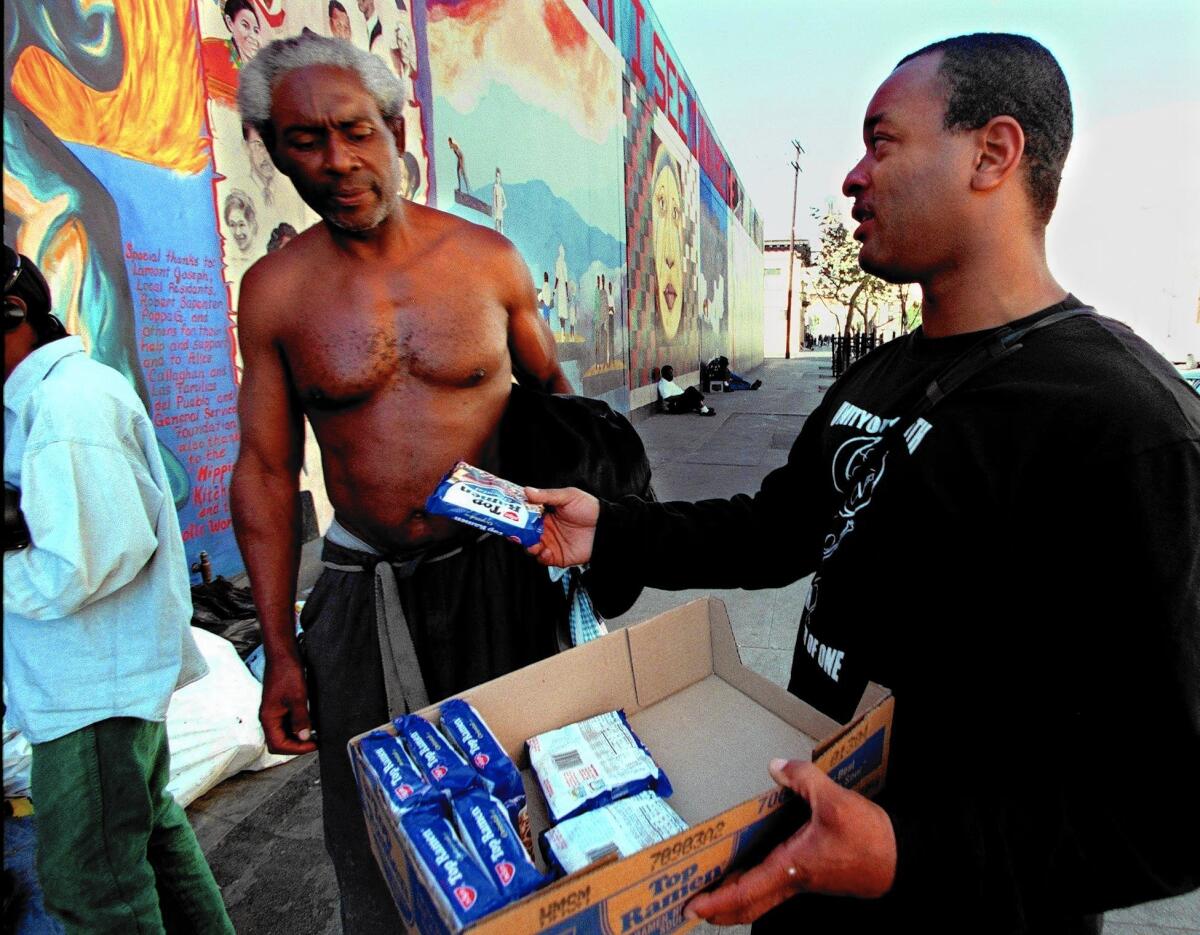

He converted to Islam, changed his name and founded Project Islamic Hope, short for Helping Oppressed People Everywhere. He began his advocacy work by feeding the homeless on the same skid row sidewalk where he once used drugs.

Najee Ali gives food to a homeless man on skid row in 1997.

In 1997, a little girl from his neighborhood, 7-year-old Sherrice Iverson, was kidnapped, raped and murdered in a Nevada casino bathroom. He went to the house of the girl’s mother and offered to help get media attention for the tragedy.

Ali accompanied Sherrice’s mother to TV talk shows. But what really thrust him into the spotlight was when he held a news conference at the girl’s grave and accused the family of trying to profit from her death.

He went on to push for Sherrice’s Good Samaritan Law, which makes failing to act when witnessing a sexual attack or physical assault a misdemeanor. The bill, which was signed into law in 2000, was the first crime bill named after a black child.

“I learned at an early age that the best way to make change is through public policy,” he said.

He went on to protest television shows and movies that cast black people in a negative light. He organized marches after police shootings. He held news conferences when he felt elected officials were not responsive to the community and candlelight vigils to remember those slain by gang violence.

Over the years, Ali became less of an outsider and more of a mainstream presence, prompting some backlash.

He’s been branded a sellout for his cozy relationship with LAPD Chief Charlie Beck, and called a mouthpiece for Mayor Eric Garcetti, whom Ali regularly praises in his column.

“I realized sometimes it is better to be inside City Hall, advocating for South L.A. as opposed to protesting outside the mayor’s house,” he said, a dig at Black Lives Matters protesters, who camped out at Garcetti’s Windsor Square home last summer.

Fighting cancer has taken a lot of out him, though his hair has grown back and he’s regained some weight. Some days, he said, he’s too tired to get out of bed.

But on the day of the Academy Awards, he made it out to Hollywood to protest the lack of diversity in the acting nominations. Only a few of the people at the demonstration in the parking lot of a shopping center knew that it would be his last protest — at least for a while.

With the microphone in his hand, he led the protesters in a chant.

“What do we want?” he screamed.

“Diversity!” the crowd answered back.

“When do we want it?”

“Now!” they shouted back.

Ali grew winded. A flurry of coughs conquered his voice. He pounded his chest to try to get it back. Before taking a sip of water, he passed the mic to a young pastor — his heir apparent.

Twitter: @AngelJennings

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.