Lucy Jones is leaving her job - to shake up more than just earthquakes

The questions were coming fast and frantic: How strong was the earthquake? Was it on the San Andreas? Is the Big One coming?

A massive temblor had struck near Joshua Tree shortly before 10 p.m., causing buildings to sway all the way to Las Vegas. As the public braced for more shaking, the media flocked to Caltech that night in 1992.

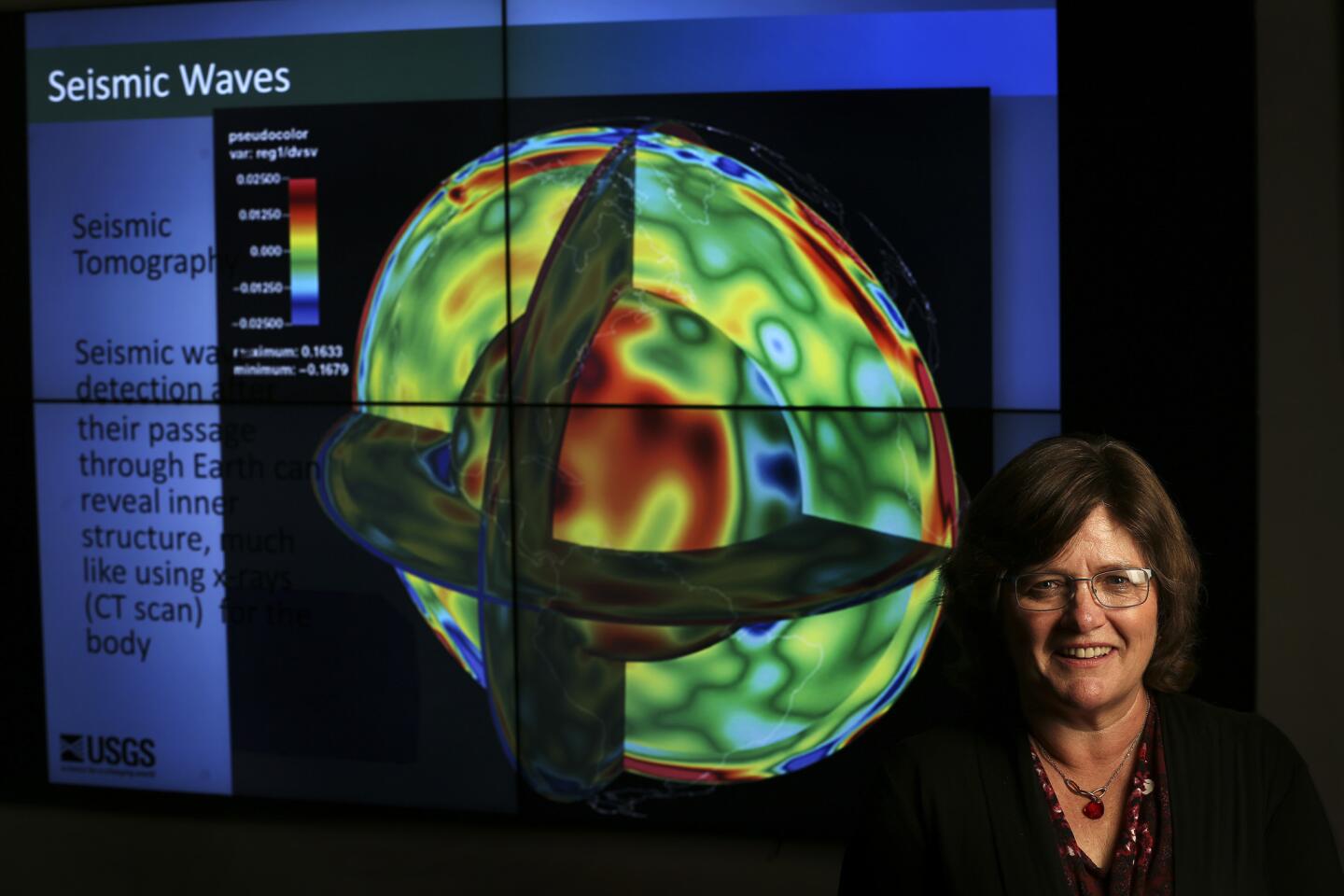

One woman seemed to have all the answers. It was a magnitude 6.1, explained U.S. Geological Survey seismologist Lucy Jones, and the odds of a larger quake in the next three days stood at 15%.

She shifted her weight and turned to the next TV camera. Cradled in her arms was her sleeping toddler.

In her 33 years with the USGS, Jones has become a universal mother for rattled Southern Californians. After each quake, she turns fear of the unknown into something understandable.

“When I give it a name, I give it a number, I give it a fault, it puts it back into a box and makes it less frightening,” Jones said. “You feel better if somebody shows they understand what’s going on.”

In a city defined by celebrity, Jones has a unique kind of fame. She’s been called the Beyoncé of earthquakes, the Meryl Streep of government service, a woman breaking barriers in a man’s world.

Her son, now 25, recently texted her: “You’re on Jeopardy!” with a photo of the clue.

Authoritative yet nurturing, the “earthquake lady” has a knack for making a complicated point so simple it seems obvious. Along the way, she has dramatically changed the way the Southland prepares for earthquakes. Buildings are safer, first responders are better equipped and millions of residents have learned that the worst thing to do in an earthquake is to run outside.

“When the big one hits, people will be living because of the work that she has done,” Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti said.

Now Jones hopes to leverage her earthquake credentials to tackle even more ambitious projects. She’s retiring from the USGS this month to help officials develop science-based policies related to climate change, tsunamis and other kinds of natural disasters.

More can be done, she said. “This is a chance to experiment.”

::

When the big one hits, people will be living because of the work that she has done.

— Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti on Lucy Jones

Jones dedicated herself to science on July 20, 1969, when Apollo 11 landed on the moon. That night, staring up at the sky in wonderment, she told her father she was going to study astrophysics.

Her father, an aerospace engineer who helped build the descent engine for the Apollo mission, fueled her interest with Isaac Asimov books. Upon giving her a copy of “Second Foundation,” he said, “The heroine is a precocious 14-year-old girl, just like you.”

But science, apparently, was for boys.

Instead of celebrating Jones’ perfect score on a science aptitude test, her guidance counselor at Westchester High School in Los Angeles accused her of cheating and made her retake the exam under supervision, she said. Once again, her score was perfect.

When Jones was accepted to Brown and Harvard — well, Radcliffe, because Harvard was for the men — her math teacher told her to go to Radcliffe because Harvard had a better class of eligible bachelors.

Jones picked Brown and enrolled in 1972. “It just really bugged the hell out of me that I couldn’t go to Harvard,” she said.

Earthquakes found her halfway through college, when she met two geophysics professors with an appealing pitch.

“Physics, you’re just making bombs,” she remembered them telling her. “Geophysics, you can play in mountains and get paid for it.”

One class and she was hooked. Her childhood ambitions to work in space had evolved into fascination with the ground beneath her feet.

Jones went on to MIT and became an early expert on foreshocks, identifying certain smaller earthquakes as possible harbingers of a bigger one. She had an interest in China — her undergraduate degree is in Chinese language and literature — and focused her research on a series of roughly 500 foreshocks to a magnitude 7.3 quake that struck the city of Haicheng in 1975.

When China’s communist government agreed to open its doors to select researchers from the U.S., Jones jumped at the opportunity and, in 1979, became the first American scientist to enter the country. Her research also took her to Afghanistan, Japan and other corners of the world before she made her way back to Southern California and the USGS, where her research enabled officials to start issuing earthquake advisories.

A 1980 conference on earthquake prediction proved fateful. She gave a talk about her research in China while a fellow graduate student ran the audiovisual equipment behind the scenes. She married that student, Egill Hauksson, who now heads the seismic network at Caltech.

They raised two sons, Sven and Niels. To make it all possible, she worked part time until Sven was in college. Being a woman meant compromise, Jones said, and she couldn’t have done it without a supportive, hands-on husband.

Being a woman also meant being mistaken for fellow seismologist Kate Hutton, who joined the Caltech-USGS team seven years before Jones.

“We don’t look anything alike — the only reason we were confused was because we were both women,” Jones said. “The guys doing the same thing don’t get called ‘the earthquake guys.’”

But, she acknowledged, the earthquake guys don’t get remembered.

Jones refuses to conform to the expectations of a man’s world. Her handshake is strong; her nail polish sparkly. Her lap is often filled with colorful yarn as she catches up on crocheting.

“She just made a blanket for our baby,” a colleague whispered, watching her fingers fly during an engineering conference.

She’s also a fixture on Twitter, where she has more than 15,000 followers. Got an earthquake question? Tweet it to @DrLucyJones and she’ll answer.

Anything can be a teachable moment. During the premiere for the earthquake thriller “San Andreas,” Jones’ commentary was often more entertaining than the movie itself.

“OMG! A chasm? If the fault could open up, there’d be no friction. With no friction, there’d be no earthquake,” she fired off on her phone.

::

Much of what Jones does today centers on this: What good is scientific knowledge if people don’t use it?

The question came to mind when she joined the California Seismic Safety Commission in 2002 and realized that crucial decisions about infrastructure were being discussed without taking science into account. For instance, a fault ruptures over a large area during an earthquake, not just at one point. If an aqueduct crosses the San Andreas to deliver water to Southern California, having three backups cross the fault at other locations wouldn’t work because a single quake would break them all, she explained over and over again.

The experience gave her a new mission: translating convoluted disaster science into tangible actions for the public.

First came the 308-page ShakeOut report, a massive research effort that laid out the myriad ways a magnitude 7.8 earthquake on the San Andreas fault would devastate Southern California. Among them: six months without water, explosions at the Cajon Pass where natural gas and petroleum pipelines meet, devastating landslides and more than 1,600 fires.

The report persuaded officials to invest in earthquake-resilient infrastructure. It also gave birth to the annual ShakeOut drill — more than 43 million people last year practiced “drop, cover and hold on.”

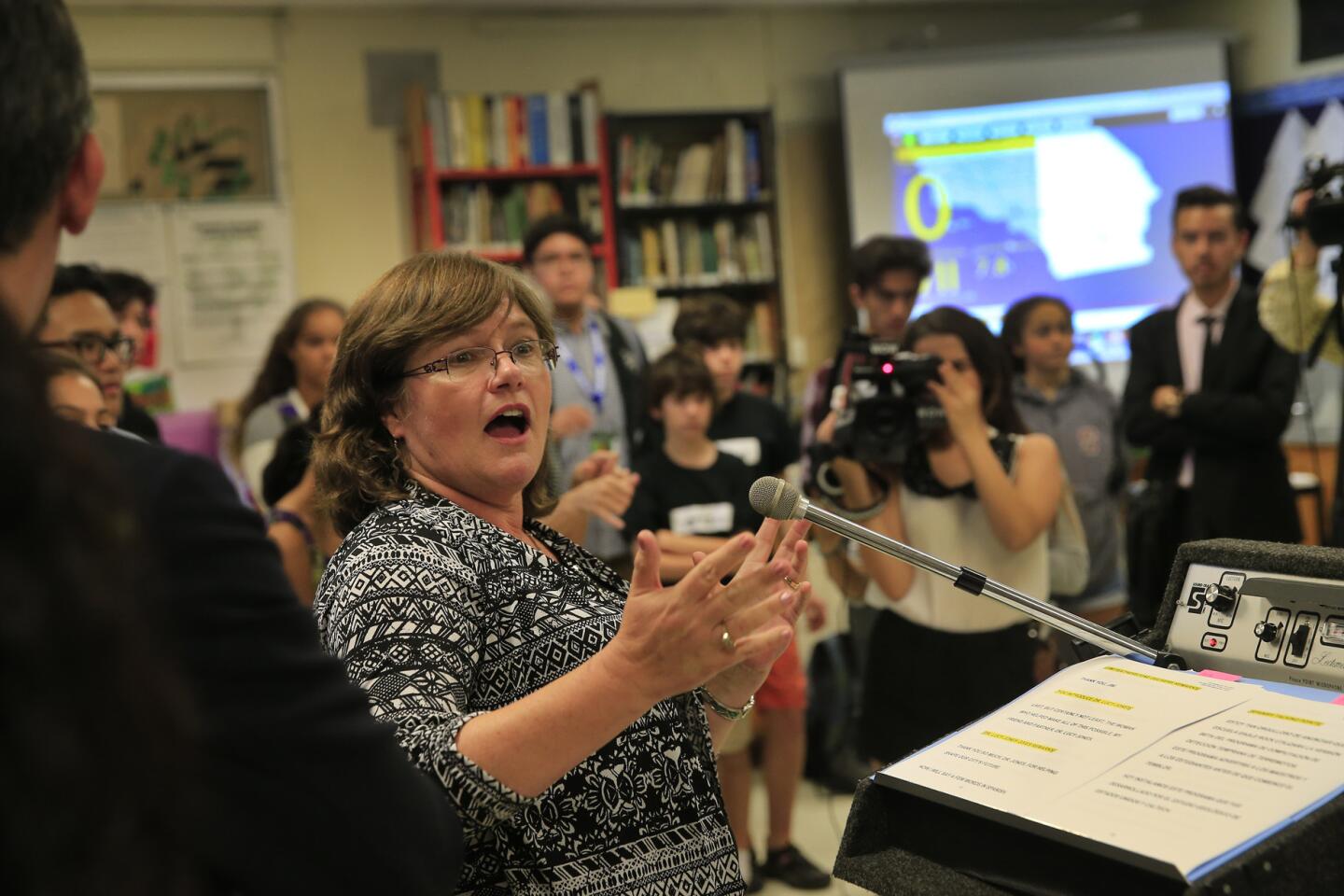

When Garcetti needed an earthquake czar to confront long-ignored risks threatening Los Angeles, Jones seemed made for the job. In more than 130 meetings with property owners, utility agencies and business groups, she preached the risk of doing nothing — a city with no cellphone service, buildings reduced to rubble and an economy in shambles.

Her tactics paid off. The city last year passed the most sweeping retrofitting laws in California history.

Her work earned her a Samuel J. Heyman Service to America medal, often referred to as the Oscars of government service. The American Geophysical Union, the Southern California Earthquake Center and many others also praised her achievements in translating science into policy.

Jones, who just turned 61, realized there was much more to do.

After her last day at the USGS on March 30, she can start raising money to create a center that bridges science and public policy. She can also partner with cities on disaster issues the way she worked on earthquakes with Los Angeles.

Climate change is a big priority. In the same blunt way she persuaded the public to confront its denial about earthquakes, Jones will try to force a conversation about the need to adapt to a warming planet.

Leaving the USGS will also allow her to devote more time to an old passion: the viola da gamba. She practices the cello-like instrument every night, and among all the media praise she’s received, what gets her most excited are two words the Los Angeles Times once used to describe her ensemble’s performance: “Exquisitely performed,” she said, relishing each syllable.

As the day came to a close, she gazed around the office she’s about to leave behind and contemplated her life beyond these walls. She headed for the front door, past the darkened offices of USGS colleagues she’s worked with for decades.

When she reaches home, she and her husband will discuss the next big scientific question. Passion, after all, does not retire.

Twitter: @RosannaXia

ALSO

Why a 99.9% earthquake prediction is 100% controversial

Scientists develop new app that uses your cellphone to detect earthquakes

Two active Southern California faults may cause a Big One by rupturing together

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.