Column: After 40 years in L.A. schools, this outspoken teacher gives the LAUSD his final grade

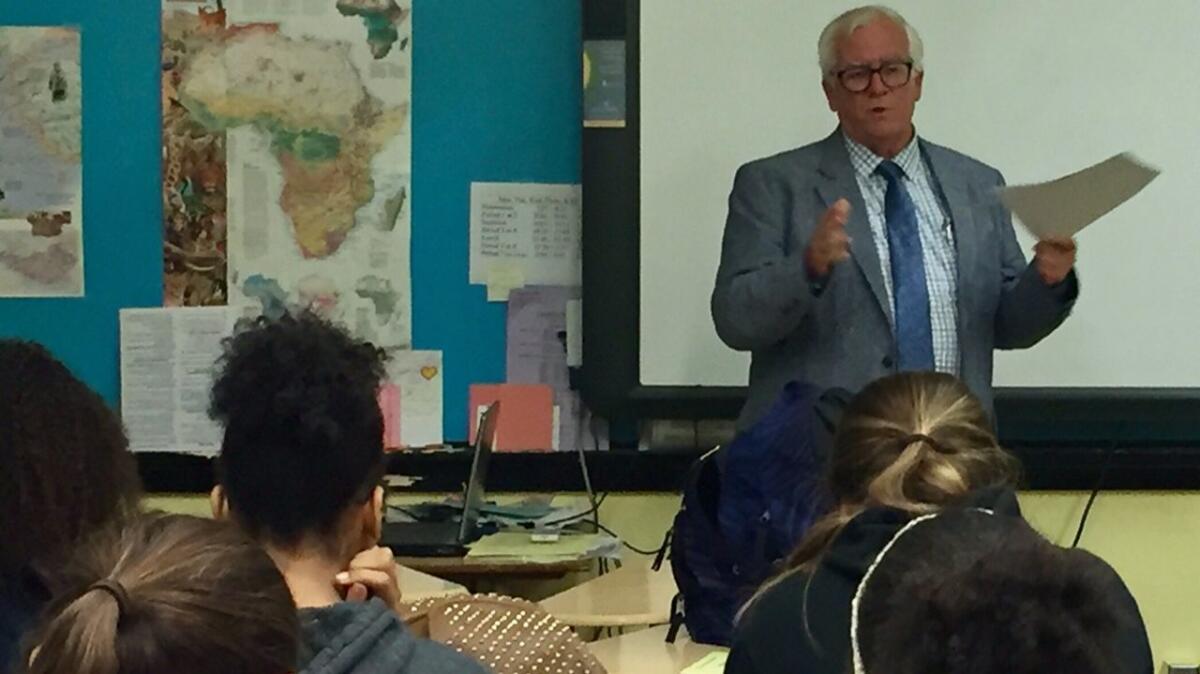

At 10:30 a.m., when all his 10th-grade AP history students had taken their seats, Jeff Horton took care of one last detail before stepping to the front of the class.

He pulled on his blue blazer and cinched up his necktie.

He does this out of respect for his students and the teaching profession. To him, this is serious business, and there would be no shortcuts on the final week of a four-decade career that has meandered from Los Angeles Unified School District classroom to boardroom and back again. Horton taught at Crenshaw High before becoming a protege of lefty school board member Jackie Goldberg and winning election to succeed her in 1991.

He’s no stranger to controversy

Over the years, Horton has found himself in the middle of controversies over a plan to break up L.A. Unified (he was opposed), the creation of a less Eurocentric approach to history (he argued that a broader world view was long overdue in multicultural Los Angeles), and on gay rights (he came out while a school board member, supported distribution of condoms, and clashed with critics who accused him of having a “homosexual agenda”).

So it’s unsurprising that Horton, a staunch union supporter, has strong views on the ever-escalating trench war over who knows best how to educate children — career educators and their union leadership, or wealthy outsiders and charter school supporters. In Los Angeles, we’ve just witnessed the most expensive school board race in U.S. history, with pro-charter forces spending $9.7 million to score two victories and take control of L.A. Unified.

Charter schools are no panacea, in Horton’s mind, even though he concedes some charter schools may work for some students whose parents are engaged and involved enough to seek out alternatives to traditional public schools.

“But that’s going to leave behind tens of thousands of kids,” he said.

The charter movement follows a narrative, in his mind, of a decades-long attack on public institutions. And now even more resources will be drained from traditional L.A. public schools, which have already been hit by California’s decline in national spending-per-pupil rankings.

Don’t parents deserve a choice?

Maybe so, but parents like options and students deserve better schools, and change isn’t coming quickly enough in a district that hasn’t been particularly well-run in the 16 years I’ve been paying attention.

As I pointed out to Horton, he teaches at an elite L.A. Unified magnet — the Los Angeles Center for Enriched Studies. Not every student wins the lottery and makes it into LACES, so what would Horton tell the parents of the unlucky students?

Horton took me back to the 1990s, when he was on the school board and the “reform” movement of the moment was something called LEARN (Los Angeles Educational Alliance for Restructuring Now). The idea was to decentralize and give schools more power to determine the specific needs of students and come up with a customized strategy — in collaboration with teachers and parents — to meet them.

Putting students first always sounds good, but there’s seldom consensus on how best to do that. Improvements under LEARN were neither swift enough nor universal, and in 1999, a new set of reformers came along. Horton and others were ousted when some of the same donors involved in this year’s charter movement (Eli Broad and Richard Riordan) backed a slate of candidates to shake up LAUSD. Horton’s seat was grabbed by Caprice Young, and he returned, eventually, to teaching.

“In ’99, our race was the most expensive school board race in history,” said Young, who looks back now on the $1 million spent on her own campaign as “chump change” compared to this year’s windfall.

Does either side have all the answers?

It leaves one to wonder whether, in 18 years, L.A. Unified will be in better shape, or we’ll be in the midst of yet another reform movement and set yet another record for political fundraising.

I’ve got issues with both sides and don’t think either will ever have all the answers. But while Horton may be disappointed in the current direction of public education after 40 years in the business, he’s had the luxury of spending most of his career in the sanctuary of the classroom. There, it all comes down to respect for students and the noble profession of inspiring them, and a good teacher can make magical things happen.

“He pushes you to where you don’t think you can go,” Luz Lopez, a 10th-grader, told me before history class began Monday morning.

Sid Thompson, who would later become LAUSD superintendent, was principal of Crenshaw High in 1975 when a rookie out of Yale walked in to apply for a teaching job.

“He started talking about what these kids need, and how can they go forward if we don’t care enough to make a commitment to them?” said Thompson, who hired Horton on the spot.

“He touched so many lives by making students understand they’re valuable and have a voice,” said Florence Saleh, who was one of Horton’s first speech class students at Crenshaw.

She said Horton implored students to follow the news, get involved and support good candidates for public office. Saleh said that in 1988, she became the first African American and woman to win a national speech competition in college, and Horton was the first person she called with the news.

She’s now a teacher, inspired in part by Horton.

“He taught me to see how students were not just students,” Saleh said. “They were my future neighbors, they were community members, and I shared that with them.”

On Monday morning, Horton’s students took turns stepping to the front of the class to talk about a historic event that had an impact on a member of their family.

A girl told about her grandfather moving the family from Louisiana to California after threats from racists.

A boy talked about his family’s flight from war in El Salvador.

A girl told about her great grandfather’s exploits with the Russian army in the defeat of the Nazis.

Horton, who says he learned a great deal from his students and was constantly re-energized by them, was radiant as history came alive in Room 202.

On the wall was a poster filled with tributes from his students.

“We will miss you,” said one.

Get more of Steve Lopez’s work and follow him on Twitter @LATstevelopez

MORE FROM STEVE LOPEZ

L.A.’s crisis: High rents, low pay, homelessness rising and $2,000 doesn’t buy much

‘Does everything have to be a Starbucks?’ A quirky L.A. landmark fights to survive

Why does a California senator want to make it harder to catch bad doctors?

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.