Charles Manson crawled from the Summer of Love to descend into Helter Skelter murders

He could have been just another grifter.

When Charles Manson rolled into California from Appalachia in 1955 in a stolen Mercury, his big ambition was to be a pimp.

In prison at Terminal Island for trying to cash a forged $43 check, he talked tradecraft with the veteran pimps inside, dabbled in Scientology and read Dale Carnegie’s “How to Win Friends and Influence People,” waiting to get out and try what he learned on vulnerable women.

Sprung in 1967, he visited a parolee he knew who happened to be living in Berkeley. If the convict had resided in Fresno or Barstow, Manson might have seen his modest criminal ambitions come to be, and the world at large would never have heard his name.

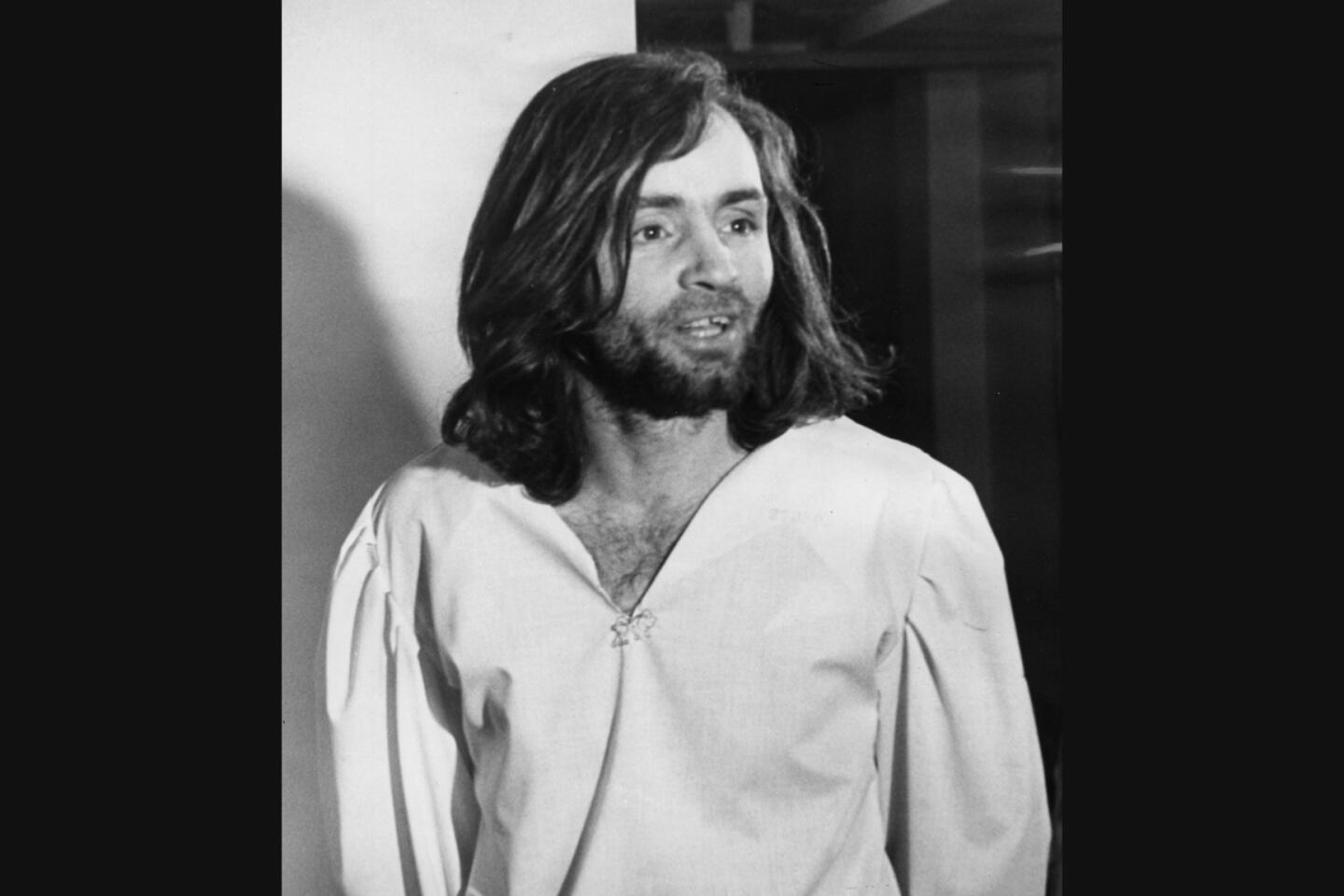

But Manson landed dead center in the country’s countercultural carnival, just a couple months before the Summer of Love. The moment he saw the sidewalk gurus in Haight-Ashbury luring young flocks of believers, he found a new calling, the perfect gig for a conniver desperate for attention.

The ensuing free-for-all of sex, drugs and dumpster-diving lasted less than two years. As Manson’s family started to sputter like its converted school bus, he kept it running on a fuel of doomsday prophesies, persuading his followers that an apocalyptic race war called Helter Skelter was coming.

He masterminded a killing rampage to serve his most insectile needs.

He had to get a killer who was likely to snitch on him released from jail, by making it appear as if the real culprit were still at large. And he needed to keep his believers from realizing he was a fraud, by making his own prophesy come true. He orchestrated the murders to look as if they were committed by black militants.

The wretched motive behind the murders was a simple con job.

But the fact that he and his family looked like hippies and did lots of LSD gave a new breed of magazine journalists just what they wanted to see—the dark side to the youth movement they’d helped invent.

Manson became the first of many people and events to end the ’60s.

To stay in the limelight, he played the madman role to epic effect.

But he didn’t have preternatural brainwashing powers.

He didn’t turn California into the Paradise Lost that so many writers had been waiting for.

He didn’t even terrify the state in the way a true sadist, Richard Ramirez, the Night Stalker, would 15 years later.

He was a scab mite who bit at the perfect time and place to be enshrined in Baby Boomer lore.

***

Manson grew up without a father, with an alcoholic mother in and out of prison. He was shoplifting by age 9 and relentlessly acting out for attention. Pinwheeling in and out of institutions, he never lasted long on the streets. As a slight-built young man in reform schools and then prison, he learned to spook predators by acting insane.

Before he was released the final time in 1967, Manson had become enthralled with the Beatles and the worship they evoked in young people. He decided he was going to be even more famous than the Fab Four, and this quest — the archetypal Hollywood story — is what turned so evil.

He used the hippie-guru role as an entree into showbiz circles.

In San Francisco, at 32, Manson looked for those women who were “broken” and alone -- anyone with a bad or missing father was a key target. He listened to them, told plain-looking women they were beautiful, acted as if he understood their depths and filled the role of father.

They called him Jesus Christ and took off in an old black school bus to claim his stardom in Los Angeles, where the scab mite, like so many others, crawled around looking for hosts.

They found a place to crash with hippies in Topanga Canyon, a house called the Spiral Staircase. They scooped up new girls willing to submit themselves to Manson’s sexual initiation.

His biggest break came when Dennis Wilson, drummer for the Beach Boys, picked up two of Manson’s girls hitchhiking on Sunset Boulevard. He took them back to his house, an old hunting lodge in Pacific Palisades that was once part of Will Rogers’ old ranch. They left without recognizing his name. But Manson knew who he was.

Later that night, when Wilson pulled into his driveway in his Ferrari, the house lights were on. Manson emerged from the house, according to biographer Jeff Guinn, “smiling and waving as if he were the host greeting a guest.”

The family moved in, and lived off Wilson’s wealth for months, while Manson relentlessly worked him and his friends, Gregg Jacobson, a songwriting partner, and Terry Melcher, a wunderkind producer, for a record deal. He ordered his “girls” to have sex with them whenever the men wanted, wrote Guinn in “Manson: His Life and Times.”

Manson talked his way into jam sessions with Neil Young, the Mamas and the Papas and others.

Young recalled him being “a little uptight, a little too intense,” according to Young’s biography, yet he and Wilson saw potential in Manson’s singing. The ones who could actually give him a record deal did not. They strung him along, enjoying the girls, avoiding confrontation.

Wilson got tired of Manson leeching off him and moved out of the rented house instead of confronting him. The Family took up residence at the Spahn Ranch near Chatsworth, where many of Hollywood’s Westerns – “Bonanza,” “The Lone Ranger,” “Zorro” – had been filmed. The girls made their stay worthwhile to the old, half-blind owner.

Every night, Manson gave his children LSD before his daily sermons, so that his banal and incoherent ramblings would be received as the word of God. He said his record would tell the world about the war to come.

Manson was quickly reaching a turning point in the cult game. The prospect of a record deal was slipping away, and some of the children were getting antsy, even dubious.

“The constant danger for gurus is that they must keep producing new wonders for their followers,” wrote Guinn. “They can’t let the act get stale or seem to be wrong about something or, worst of all, to fail publicly.”

So he doubled down on Helter Skelter. They needed to start preparing.

They found an isolated compound in the Panamint Mountains of Death Valley, and his followers began earnestly looking for the opening to a bottomless pit where they would hide.

At the same time, Manson was still desperately trying to get an audition with Melcher.

When Melcher agreed to watch him perform at Spahn Ranch in May of 1969, Manson stopped all preparations for Helter Skelter. He still just wanted to be famous.

But Melcher left unimpressed.

Events spiraled quickly after that.

Manson started shaking down anyone he could for money to get the dune buggies and supplies they needed for the desert. He had an associate, Bobby Beausoleil, go to Topanga and hold the owner of the Spiral Staircase hostage until he gave up all his money.

When the owner threatened to go to police, Manson told Beausoleil, “You know what to do.” Beausoleil stabbed him to death and wrote “POLITICAL PIGGY” in blood, with a paw print, the symbol of the Black Panthers, to put the murder on black militants.

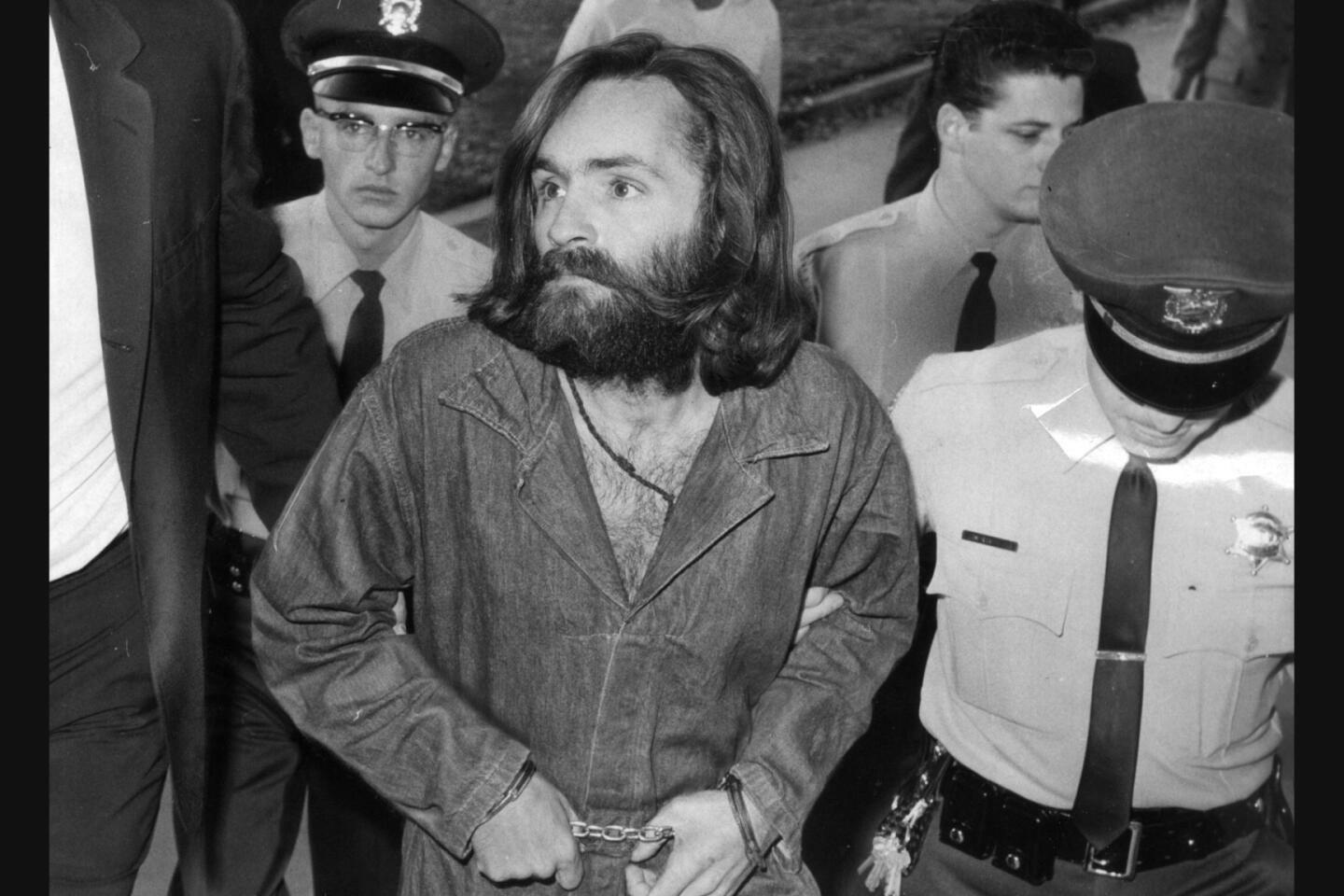

Beausoleil was arrested near San Luis Obispo with the victim’s Fiat and the bloody knife in the tire well. Manson panicked, knowing police would pressure him to talk. Feeling caged, he sent his followers out to kill more people on two hot August nights, scrawling similar notes, so it looked as if the true killer was still stalking prey and police would be forced to release Beausoleil. And this would foment Helter Skelter, and his “children” would see that he truly was God.

But most importantly, Manson didn’t commit the murders himself, so in his mind, he wouldn’t go to prison for them.

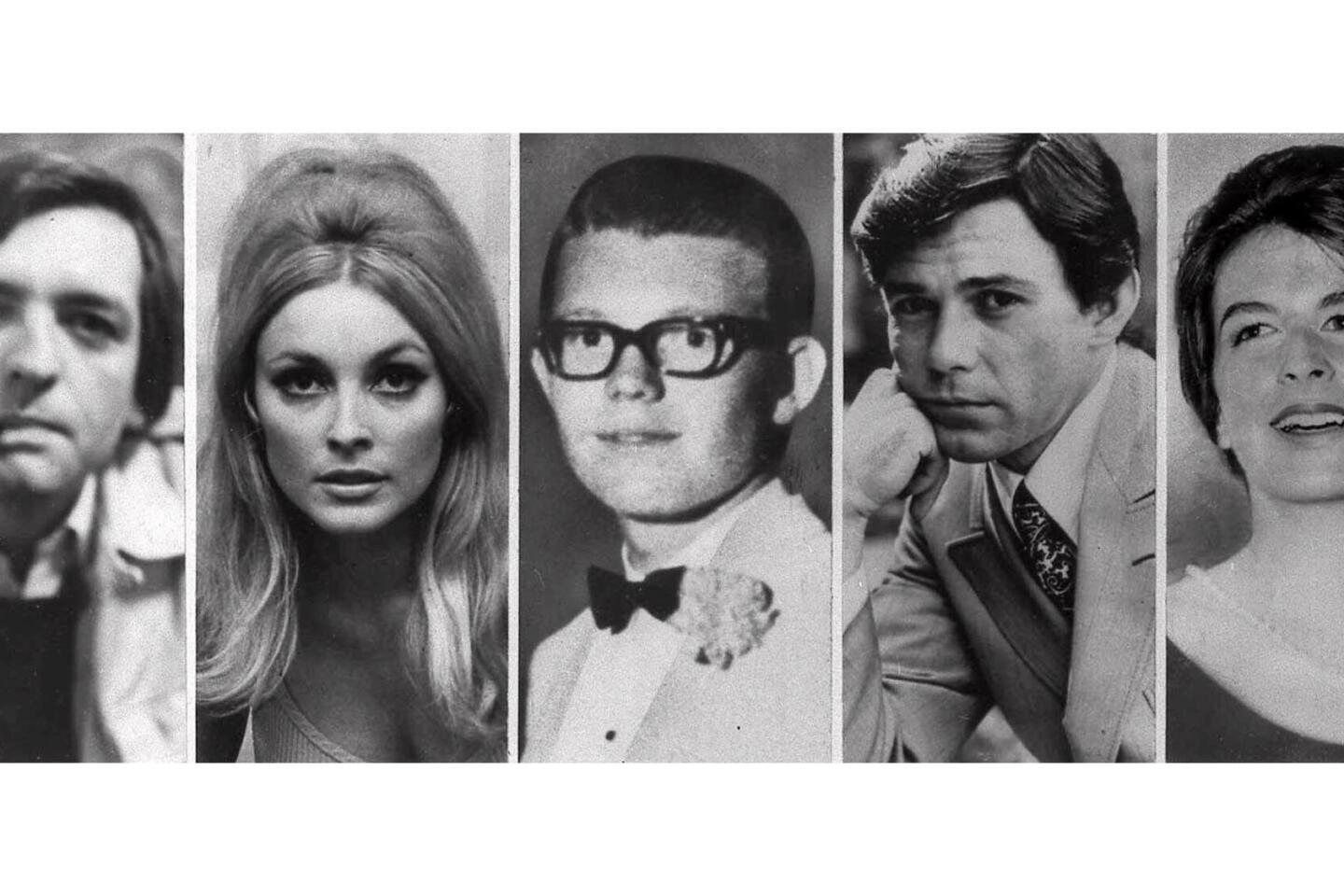

Nine people died in the carnage, including the actress Sharon Tate. The lurid details of the first night’s murders at the Tate house -- “PIGS” scrawled in blood on a wall; speed, pot and LSD found in the Porsche of one of the slain -- set off wild rumors and paranoia around Los Angeles.

“The murder was still etched across every conversation three months after the event, with the killers still at large to make nightmares of the city,” wrote Barry Farrell in Life magazine.

Speculation ran rampant about the sexual and drug proclivities of Tate and her husband, director Roman Polanski, and Hollywood in general.

“Every story promotes the murders into assassinations, crimes of logical consequence in which some vision of the victims’ way of living makes them accomplices in their own deaths,” wrote Farrell. “It is as if no one is satisfied with the crime until it can be perceived as a political act — the murder of a lifestyle.”

Joan Didion described the sense that drugs and open sex had upended the old traditions so swiftly that anything could happen.

“Everything was unmentionable but nothing was unimaginable,” she wrote in “The White Album.” “This mystical flirtation with the idea of ‘sin’ — this sense that it was possible to go ‘too far,’ and that many people were doing it — was very much with us in Los Angeles in 1968 and 1969. … The jitters were setting in.”

The morning Los Angeles woke to hear of five people murdered on Cielo Drive, “the tension broke,” wrote Didion. “The paranoia was fulfilled.”

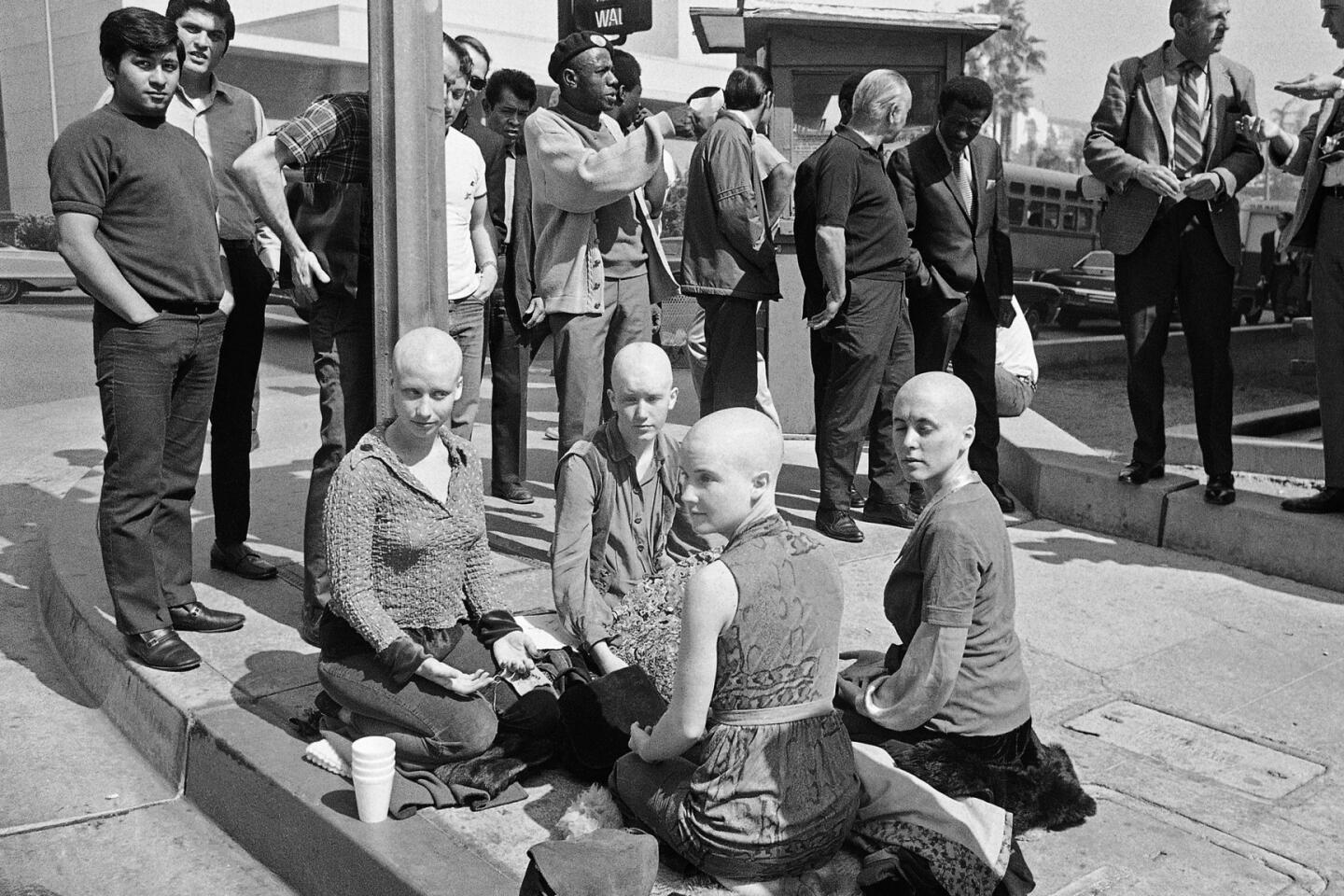

But when the Manson family was arrested for the crimes four months later, the critical gaze shifted from the sins of Hollywood to the sins of America’s youth — the fear that any flower child from Sioux City or Peoria could be brainwashed into becoming a sex-crazed killer.

“The Dark Edge of the Hippie Life,” Life magazine proclaimed on its cover about the Manson family.

“The Los Angeles killings struck innumerable Americans as an inexplicable controversion of everything they wanted to believe about the society and their children,” wrote the magazine’s Paul O’Neill, “and made Charlie Manson seem to be the very encapsulation of truth about revolt and violence by the young.”

Speed, needles and the violent ethos of hard drugs had already taken over in Haight-Ashbury.

Just five days after Manson hit the news, the Altamont Free Concert opened, billed as “Woodstock West.” But fights erupted in the crowd, and the Hells Angels, hired for security, brawled with spectators, fatally stabbing a man who pulled a gun.

In psychedelic terms, the end of 1969 turned into the sour acid trip that had you lockjawed in terror, clenching to keep your molecules from flying into space.

In that one week that December, the ’60s died twice. And so began the sense of a cultural skid-out, tracking from the Spahn Ranch to the drug deaths of Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin to the kidnapping of Patty Hearst and buckets of cyanide-laced Kool-Aid in Jonestown.

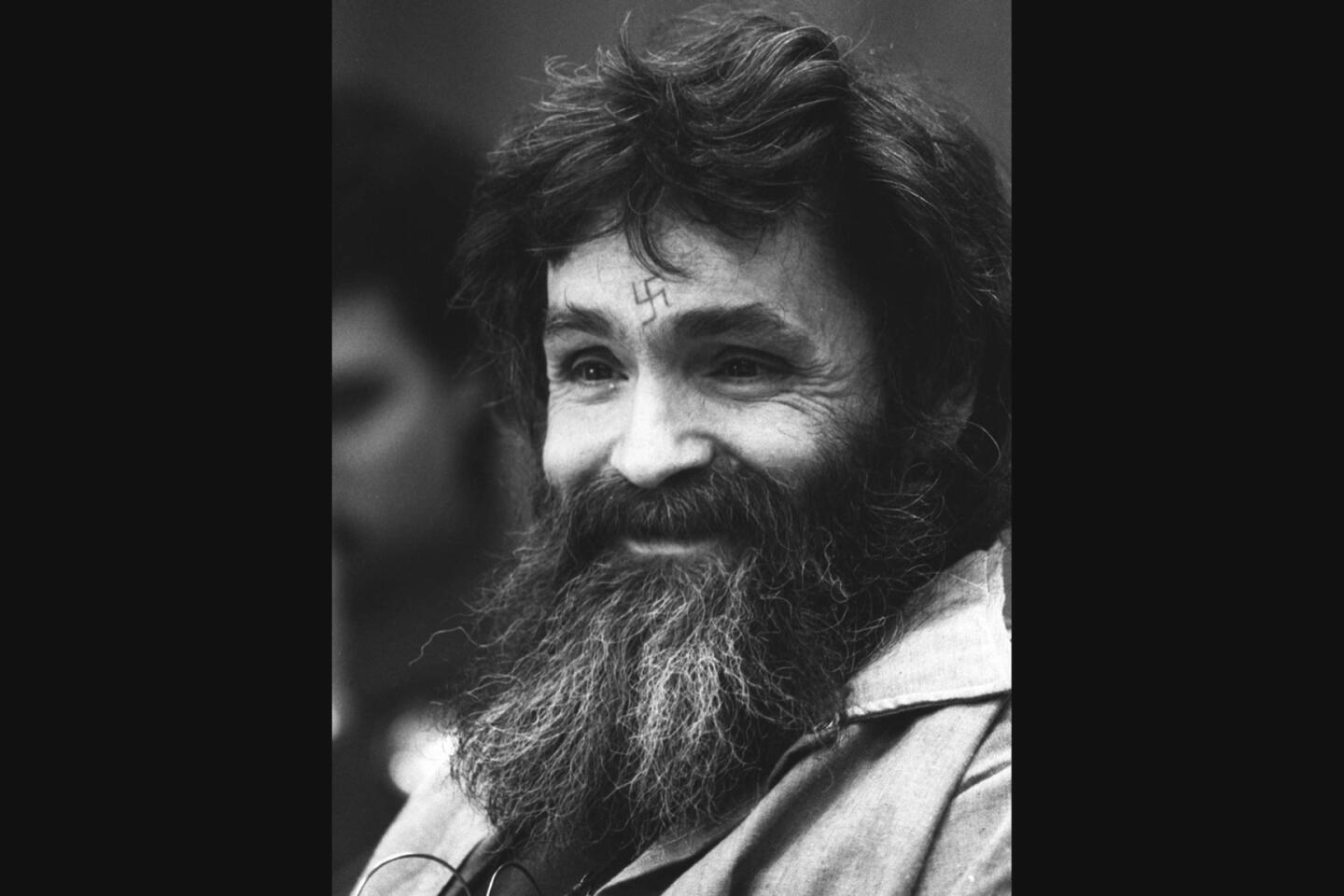

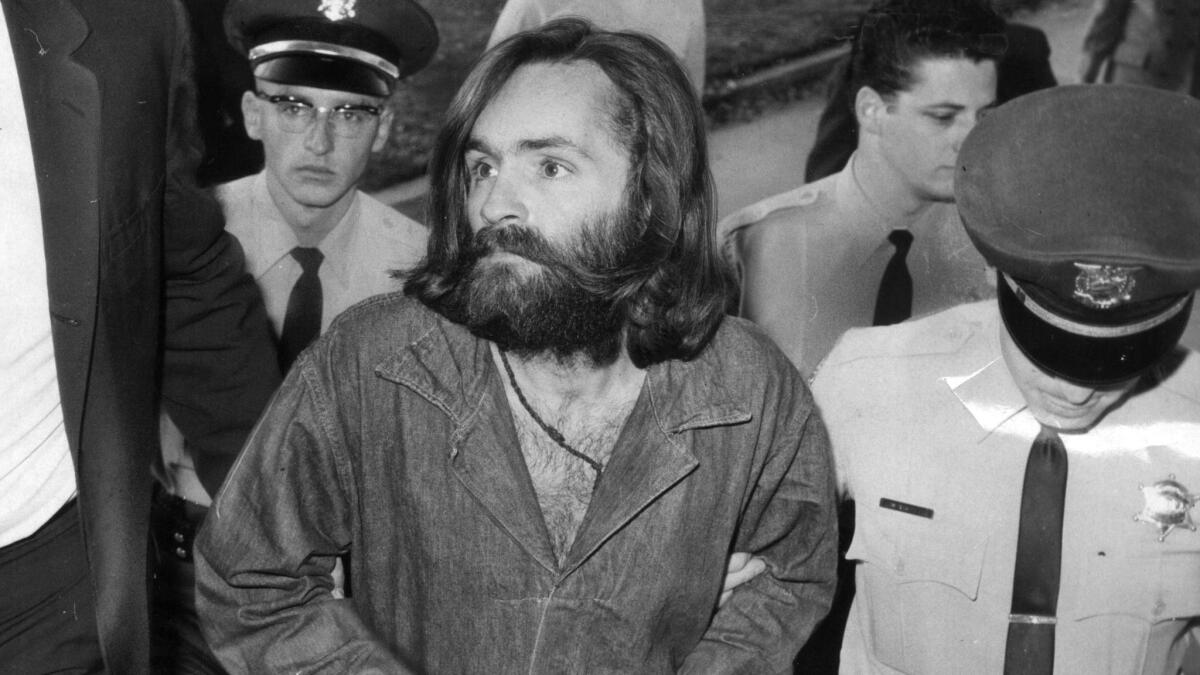

Manson went to trial with three followers involved in the murders. The trial was a freak-show like America would not see until the Jerry Springer era. Manson, a fresh X gouged in his forehead, relished the crowds that had come to see him. He ranted and made threats and crazy demands. His main soldier, Susan Atkins, fell into histrionic cries of stomach pain at one point. Other female family members converged outside the Hall of Justice — copycat Xs in their foreheads — posing for pictures with gawkers, playing patty-cake on the sidewalk.

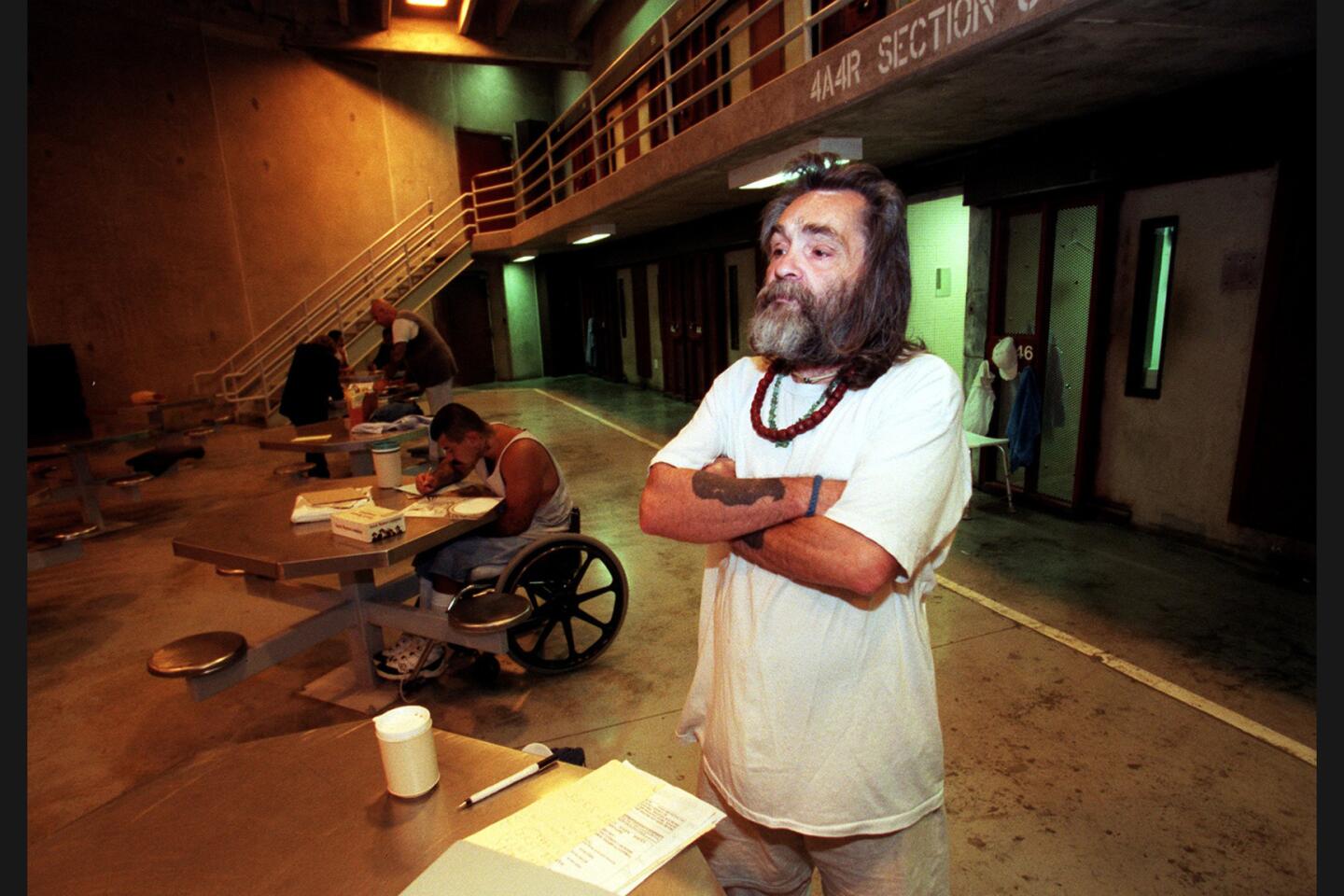

Manson and the three others were sentenced to die in the gas chamber, but when the death penalty was abolished in 1972, he would get his regular parole hearings and TV interviews, and the public was sentenced to never forget him.

He embellished his X into a swastika, and kept up the insane act he learned as a kid — telegraphing the reality stars to come — a tabloid mainstay, a scab mite itching our consciousness to the very end.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.