For neighbors near warehouse fire, an outpouring of sympathy for strangers in their midst

They would come in twos and threes, mothers pushing baby strollers, grandmothers on walkers, day laborers on their way to nearby street corners to wait for work, all wanting to see and maybe to understand the horror that had erupted in their neighborhood.

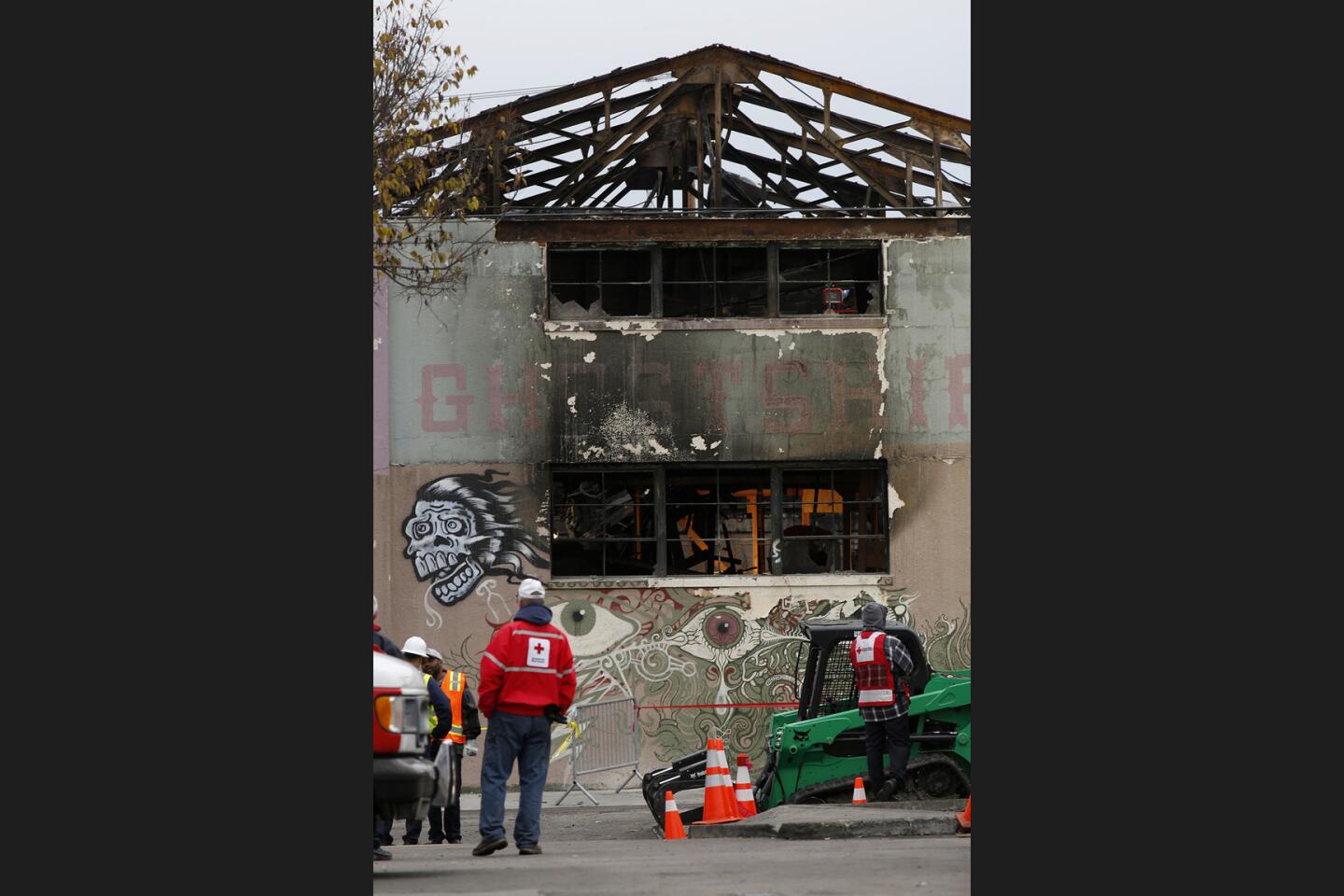

“No bueno,” muttered an elderly street vendor who had pushed his ice cream cart to the corner of Fruitvale Avenue and International Boulevard, across the street from the charred and gutted warehouse known as the Ghost Ship. He made a flicking motion with his right hand, as if tossing a match, and shook his head.

For many denizens of the Fruitvale district, the deadly fire that brought to their neighborhood convoys of fire trucks, heavy equipment and coroner wagons, along with media satellite vans and hovering news helicopters, also provided a jarring introduction to an artists’ colony that had arisen in their midst.

“I never noticed it before,” said Tiffany Castellon, a school secretary who lives near the Ghost Ship. “It was just a building. I never knew anyone lived there.”

In Oakland’s Fruitvale neighborhood, affordable housing in an issue, a resident says.

She was walking her 9-year-old son to school when she came across one of the makeshift memorials of flowers, candles and condolence notes that have popped up outside the security perimeter since the Friday fire.

“This is our community, too,” she said. “We didn’t know any of the victims, but we just want to show our support to the families.”

Castellon and other residents described Fruitvale, situated in the flats southeast of downtown between two freeways, as a largely Latino district of working-class families and small shops. International Boulevard, a broad commercial street, runs down the middle. Its residential side streets are filled with apartment houses and tidy, if tired, bungalows.

In California, such descriptions often have a short shelf life, as many of the state’s neighborhoods — animated by fluctuating real estate markets and shifting immigration patterns — are ever in motion.

This is especially true in the San Francisco Bay Area, where a rising economy driven by the tech industry has lifted housing costs to the point where a $300-a-month space in an out-of-the-way warehouse begins to seem reasonable to, say, struggling artists.

On the surface, the phenomenon appears not to have extended too deeply into Fruitvale, a district where the ethnic mix is always changing, most recently drawing many Central Americans. But there are signs this won’t hold for long. Investors have begun to build and propose additional loft spaces and luxury condos near the Fruitvale Bay Area Rapid Transit station, just a few blocks from where the warehouse burned.

Walking along International Boulevard, City Councilman Noel Gallo pointed out an empty lot in which a sports shoe company plans to build a high-end, multistory store; a charity store whose owner is “itching” to put it on the market; and a newly renovated brick building where rent is expected to rise.

It was just a building. I never knew anyone lived there.

— Tiffany Castellon, Ghost Ship neighbor

“What is going to happen to the people living here now?” he asked. “What is going to happen when their rent goes from $650 a month to $1,300?”

He answered his own question: “When property owners raise rent on them, these people will be displaced.”

The 63-year-old Fruitvale native already has seen in his lifetime various forces of change at work in his neighborhood: light industry giving way to retail.

The district is still “crime challenged,” Gallo conceded, with International Boulevard active with street prostitution by night. The Fruitvale BART station was also the site of a controversial police shooting that led to unrest and was depicted in a movie.

But many residents said they see improvements.

“In the daytime, it’s quiet,” said Becky Shao, who manages an auto repair shop directly across International Boulevard from the fire scene. “But at night it’s kind of … busy.”

Shao, too, had no idea artists were occupying the warehouse across the street. Until the fire.

“When I saw it on the news,” she said. “I knew that the location was next to us, and I was surprised.”

Of course, some people who live in nearby houses told of hearing music coming from the warehouse on weekend nights. And some of them, and a few shop owners, said they noticed, and complained about, the clutter surrounding the building – everything from a boat trailer to pianos to wood scraps.

“But the people themselves, they pretty much kept to themselves,” said John MacLeod, whose Acme Fire Extinguisher Co. has been in the family for three generations. “I never saw them much.”

“There was one guy I do remember,” MacLeod said. “He would walk one dog and carry another. But other than ‘hello’ … that’s as far as it went.”

Still, though the victims may have been strangers to them, the Fruitvale residents who converged on the perimeter of the fire scene made clear they came with something more than curiosity.

“I honestly did not know this was there,” said Yolanda Marie Contaxis, who works at a funeral chapel two blocks up Fruitvale. She was on her way to volunteer as a grief counselor for families of the deceased. “But this is at our doorstep, and we have to do what we can.”

Twitter: @peterhking

ALSO:

Search for bodies in Oakland warehouse fire should be completed by midnight

Before deadly Oakland fire, Ghost Ship warehouse was scene of legal sparring and tenant drama

Victims of the Oakland warehouse fire: Who they were

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.