L.A. City Council OKs crackdowns on homeless encampments

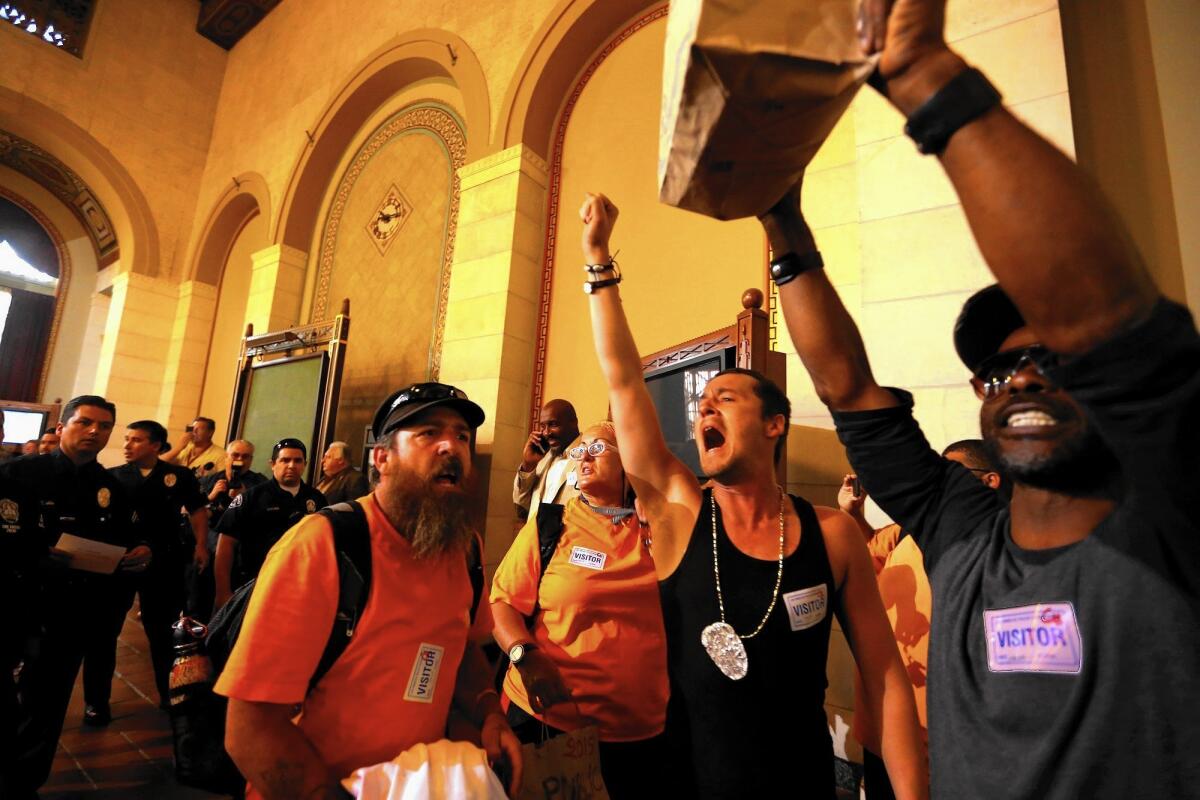

Members of the Los Angeles Community Action Network, a homeless advocate group, protest at City Council meeting where a crackdown on homeless encampments was approved.

The Los Angeles City Council gave final approval Tuesday to an aggressive crackdown on street encampments, setting the stage for the first major homeless sweeps in the city in decades.

Mayor Eric Garcetti said he would sign the two ordinances, which authorize seizure and in some cases destruction of makeshift shelters and other property of homeless people. The mayor also said he supported proposed amendments that would drop a criminal penalty for violations and eliminate medication and personal documents from the list of belongings that can be confiscated.

Council President Herb Wesson said the council would take the amendments up soon, but he did not rule out enforcing the new ordinances before any changes go through.

“I don’t anticipate a lot of early enforcement,” Wesson said before the council meeting, which was briefly disrupted by a noisy demonstration by homeless advocates. “It is not uncommon for us to move forward then work on refining language.”

Garcetti did not say whether he supports immediate enforcement, but said through a spokesman that he backs an ordinance he believes needs fixing because existing law on homeless property is “legally untenable.”

The new laws, which will take effect as soon as they are signed and published by the city clerk, were approved in response to a four-year rise in the homeless population and an 85% increase in car camping and homeless street camps countywide. City Administrative Officer Miguel Santana, in a recent report, estimated that the city spends $100 million dealing with homelessness, more than half of it going to the police budget.

Business leaders praised the measures as a balanced approach to removing unsightly tents that block public sidewalks and alleys and pose health and safety concerns.

“We’re thankful for a new city response that’s balanced and responds to a growing public health and safety crisis,” said Raquel K. Beard, executive director of the business improvement district that covers skid row.

Opponents, including Councilman Gil Cedillo, who cast the lone no vote, said the measures would criminalize homelessness while doing nothing to help people off the streets.

“We should have a war on poverty, not on the poor,” Cedillo told the council.

“We should be building our way out of homelessness and not policing our way out,” Pete White of the Los Angeles Community Action Network said at a news conference before the meeting. Police escorted LA CAN members out of the council chambers after they staged a bit of political theater during the meeting, portraying police handcuffing and hauling off homeless people and taking their tents.

An overwhelming majority of the city’s 26,000 homeless people live in the streets. Shelter directors and housing experts say their facilities are full and there is nowhere else for homeless people to go.

The new measures — one governing streets and sidewalks, the other parks — allow authorities to take homeless people’s property on 24-hour notice even if they are present and claiming it. “Bulky” items, such as sofas and mattresses, can be confiscated and destroyed with no warning. Homeless people, under a court order, can sleep in the streets from 9 p.m. to 6 a.m., but their tents must be taken down and stored in the daytime.

Seized property will be impounded for 90 days, but the city’s only storage facility is on skid row. Advocates complain it’s a long haul for those living in other areas of the city.

The measures drew condemnation from national advocates, who said the city is running against the tide of recommended practices in the fight to end homelessness.

“It costs money to send police out after homeless people,” said Maria Foscarinis, executive director of the National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty in Washington, D.C. “What they should be doing is taking money and putting into housing.”

The U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness in a 2012 report endorsed 24-hour emergency access to shelter or “safe havens” as an alternative to homeless sweeps.

“Law enforcement engagement not only provides a temporary solution to the problem, it contributes to a culture of distrust, pitting individuals experiencing homelessness against the broader community,” the report said.

Criminal penalties, the report added, “actually exacerbate the problem by adding additional obstacles to overcoming homelessness.”

Attorney Peter Schey, president of the Center for Human Rights and Constitutional Law Foundation in Los Angeles, said immigrants convicted under the ordinance could be turned down for residency or citizenship. He also said the city, which has lost a long string of court decisions over its homeless enforcement practices, runs the risk of further litigation.

The council passed the new laws as urgent measures two days before the first meeting of the council’s new homelessness committee. At its meeting, committee members called for new restrooms, showers, shelters and storage facilities for homeless people, but did not identify revenue sources. The proposals were referred to staff for study.

“I don’t see how the city can acknowledge the involuntariness of the homeless, make breezy poetry about intent to provide solutions in the distant future and then feel entitled and moral to confiscate people’s property in the immediate,” said Alice Callaghan, a longtime homeless advocate and director of a skid row school for immigrants’ children.

“It’s a first step of a longer conversation on the issue of homelessness, but an important first step,” Beard, of the business improvement district, said.

Twitter: @geholland

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.