More than 1 million tons of rock and dirt have to be moved off Highway 1. But how?

A massive landslide along California’s coastal Highway 1 at Mud Creek buried the road under a 40-foot layer of rock and dirt. (Video by Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

Geologists and engineers crowded a conference room in San Luis Obispo on Wednesday to address the latest assault upon California’s most revered roadway.

Yet another stretch of Highway 1, that improbable serpentine hemming the continent’s western edge, had abruptly disappeared.

No one in the room was shocked or surprised. The scientists and builders knew what they were up against.

A week earlier, sensors in the mountains had picked up increased ground movement at a site 10 miles north of Ragged Point. On-site crews and equipment were evacuated, gates closed and locked.

On Saturday at 9:30 a.m., a hillside near a small ravine known as Mud Creek collapsed, sloughing an estimated 1.5 million tons of rock and mud — about a million cubic yards — over the highway and into the ocean.

The landslide was a third of a mile wide and 40 feet at its deepest. What once was a steep drop into the Pacific was now a broad, sloping bench extending almost 250 feet beyond the shoreline. By some estimates, the collapse had added 15 acres to the coast, a little more than 11 football fields including the end zones.

And the worst might not be over, said field inspectors who had just returned from the slide. Listen closely, and you’ll hear a sound of water running like rain through the rocks and dirt. The slide at Mud Creek is still moving.

“This is a big one,” said Rick Silva, a Caltrans engineer who had phoned in for the meeting. “It might be a once-in-a-career slide.”

But Silva and the gathered geologists and engineers were unfazed.

Their worst-case scenario had always been the 1983 slide that buried Highway 1 near Julia Pfeiffer Burns State Park for 14 months with 4 million cubic yards of rocks and dirt.

This one might pose even bigger problems, but now they’re more familiar with these notoriously temperamental mountains. And they’re confident they will once again succeed in carving a new route through the rubble, opening the coast for businesses, residents and the million annual tourists drawn to its hairpins and panoramas with a bucket-list fervor.

It will take time though.

Land in motion

The Santa Lucia Mountains, extending from Cambria to Carmel, are particularly vulnerable to landslides.

This coastal range reveals one of California’s defining tectonic features — the subduction of the Farallon Plate under the North American Plate — and the bedrock here, says Noah Finnegan, a geologist with UC Santa Cruz, has “a tortured history.”

“They have been pervasively fractured and broken up,” he said. “They have a hard time holding a steep slope.”

In such an environment, water and gravity are great levelers. The steep and narrow canyons of the coast are frequently scoured by debris flows, torrents of water skimming off topsoil and rocks at disastrous velocities. The formidable hillsides are subjected to deeper subsurface forces that come into play as groundwater shifts the frictional properties of the soil.

It’s not uncommon, Finnegan said, that big slides occur long after the last rainfall: “Groundwater response is often delayed.”

This year’s battle for Highway 1 began in January after a series of storms pummeled the Central Coast and saturated the Santa Lucias. By midwinter, some stations had reported up to 83 inches of rain.

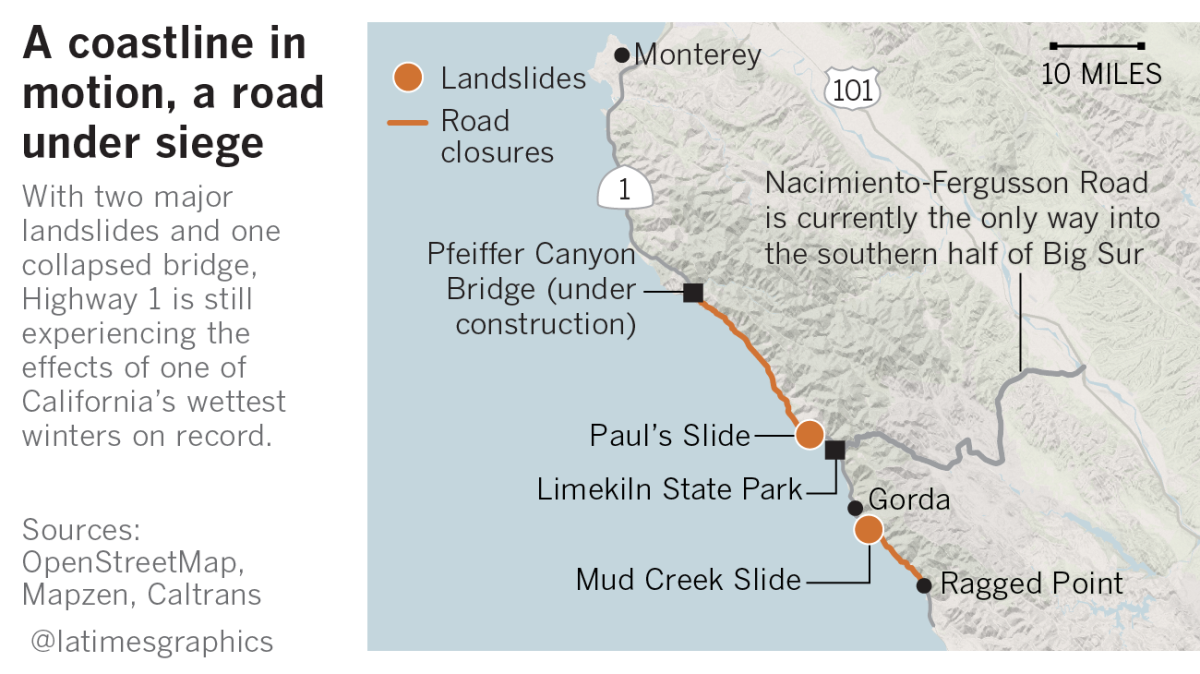

In early February, the California Department of Transportation, the agency responsible for maintaining Highway 1, noticed the first major problem: The ground beneath the Pfeiffer Canyon Bridge in the Big Sur River valley had begun to slide and undermine a concrete column’s foundation.

Four days later, the slumping bridge had to be condemned. The tightknit community of Big Sur was suddenly divided.

After a deluge that arrived over the Presidents Day weekend, the agency encountered two problems of an entirely different scale to the south on either side of Limekiln State Park.

Here, cliffs rise at near-right angles to the highway, which is protected by giant skeins of webbing that catch the falling boulders. At one turn, engineers devised a structure known as the rock shed to protect the road. It took five years to build and from a distance looks like a fortress out of Tolkien’s Middle-earth.

Just north of there is a famously troublesome part of the highway known as Paul’s Slide, nearly 1,000 feet where skip loaders and dump trucks have spent years cleaning up the rocks and boulders that periodically hammer the asphalt.

Having studied this particular hillside for more than a decade, engineers were close to finalizing a plan, relocating up to 170,000 cubic yards of material from above the road to a terrace below the road. Then the winter rains began to fall, and the ground began to shift.

By the end of February, the southbound lanes at Paul’s Slide had collapsed, undermined by the water running under the road.

By then, Caltrans had closed Highway 1. Only local residents and special deliveries were allowed through on a partially reconstructed road, only one lane wide.

Through March, engineers and construction crews worked fast to shore up the standing road, allowing only occasional deliveries and residents to pass through at designated times.

On Thursday, however, geologists detected land movement and closed Paul’s Slide for further evaluation.

Add to that the massive slide at Mud Creek, 13 miles to the south, and it’s easy to see hubris in an engineer’s confidence over the control of this coast.

Sensing a landslide

Ryan Turner, a geotechnical engineer with Caltrans, glimpsed the possibility of massive land failure at Mud Creek weeks before it occurred.

Standing on the shoulder of Highway 1 on a March afternoon, he noted a small fissure in the hillside that had opened up days earlier. Now the highway had sunk four feet.

Turner pointed out a series of triangular wedges in a slope rising 1,000 feet above the road and covered with the stubble of yucca and rabbitbrush. He thought about the 1983 slide, but he knew he didn’t have enough information to draw any conclusions.

New springs, freshets of water popping out of the mountain and onto the road, created small gullies almost daily, and mud tainted the blue ocean the color of a café latte in broad eddies circling up the coast.

“It is made worse by water,” Turner said. “

As he spoke, skip loaders did triage, steadily clearing the dirt and mud. Spotters, their eyes trained on the cliff, blasted air horns to signal an imminent danger if and when more medicine balls tumbled down, thudding to a stop on the road. Some, the size of VWs, had already fallen.

“Working out here is like Groundhog’s Day,” Turner said. “Each day crews are repeating the steps of the previous day just to stay even with the ongoing damage.”

Throughout the spring, Turner and his colleagues have collected information about Mud Creek. They spent days bushwhacking through poison oak, studying aerial photos and radar movements of the land.

“Is the whole land mass moving, or is it just these smaller slides?” he asked. “My experience says something bigger is going on.”

Opposing forces

To understand the dynamic of a landslide, Turner said, you have to understand that hillsides are held together by two competing forces: a driving force that wants to push the hillside down and a resisting force that holds the hillside up.

“To improve stability, we must reduce the driving pressure and increase the resisting pressure,” he said, a strategy that informs the long-term fix at Paul’s Slide.

But at Mud Creek, such a fix was not feasible. There was no terrace of land below the road to deposit material removed from above the road, and depositing that material into the ocean was not an option.

During the 1983 slide, crews shoveled the excavated dirt and rocks into the ocean, a process that ended up creating a beach where there once was a cove.

Today, the ocean north of Cambria is inside the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, governed by regulations that prohibit discharges into the ocean, said Scott Kathey, who works with the sanctuary.

The engineers thought they had a solution: a side-hill viaduct, essentially a 1,000-foot-long bridge with consecutive spans running adjacent and at a distance from the cliff, so that any debris would pass underneath the structure.

To explore this option, a drill rig had been brought on scene on the north side of the slide.

Then the ground began shifting anew. And their solution was scrapped.

No one was present during Saturday’s slide, but other large landslides have produced seismic waves, tsunamis and, in the case of the disastrous mudslide in 2014 that buried Oso, Wash., a din that witnesses said sounded like “a 747 about to crash.”

Has Mother Nature prevailed?

Caltrans hopes to open north- and southbound lanes at Paul’s Slide in July.

Construction of the new bridge spanning Pfeiffer Canyon is on track for completion later this year, and the Nacimiento-Fergusson Road connection linking U.S. 101 with Highway 1 provides limited access to the coast.

Following Wednesday’s meeting, geologists and engineers are scrambling to learn whether they can expect more failure of the hillside at Mud Creek.

They are using drone and aerial reconnaissance to map the region and evaluate the stability of the slopes above and below the highway.

The topography has changed so much that the geologists need to redraw the map of this part of the coast.

It’s too early to suggest a solution, said a Caltrans spokesperson. But that’s a far cry from conceding defeat.

Twitter: @tcurwen

Twitter: @bvdbrug

ALSO

A devastating cycle of fire, record rain and huge landslides batters California's Central Coast

Don't give up on visiting Big Sur. Here's what's still open after that massive landslide

A massive landslide that closed Highway 1 is part of a $1-billion problem for California

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.