Must Reads: Climate change will be deadlier, more destructive and costlier for California than previously believed, state warns

Heat waves will grow more severe and persistent, shortening the lives of thousands of Californians. Wildfires will burn more of the state’s forests. The ocean will rise higher and faster, exposing California to billions in damage along the coast.

These are some of the threats California will face from climate change in coming decades, according to a new statewide assessment released Monday by the California Natural Resources Agency.

The projections come as Californians contend with destructive wildfires, brutal heat spells and record ocean temperatures that scientists say have the fingerprints of global warming.

“This year has been kind of a harbinger of potential problems to come,” said Daniel Cayan, a climate researcher at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography and one of the scientists coordinating the report. “The number of extremes that we’ve seen is consistent with what model projections are pointing to, and they’re giving us an example of what we need to prepare for.”

State leaders vowed to act on the research, even as the Trump administration moves to unravel climate change regulations and allow more pollution from cars, trucks and coal-fired power plants.

“In California, facts and science still matter,” Gov. Jerry Brown said in a statement. “These findings are profoundly serious and will continue to guide us as we confront the apocalyptic threat of irreversible climate change.”

The state’s assessment draws on the latest science, including more than 40 new peer-reviewed studies, to project the effects of the continued rise in greenhouse gases on California’s weather, water, ecosystems and people and offer guidance on how officials across the state might adapt.

It’s the fourth such report since 2006, when Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger ordered a climate change assessment as precursor to the Global Warming Solutions Act, the pioneering law California adopted that year to cut greenhouse gas emissions to 1990 levels.

This latest one for the first time scales down global climate models to project climate’s effect at the regional level or smaller. That approach is intended to provide local officials on the ground with more relevant, community-level information they can use to prepare.

“The difference between the San Joaquin Valley and the nearby coastal or Sierra Nevada mountains is enormous, so we have to have ways to unpack the large-scale global model calculations,” Cayan said.

Rising temperatures, deadlier heat waves

California has already warmed 1 to 2 degrees since the beginning of the 20th century as a result of the human-caused buildup of greenhouse gases. That figure could rise to between 5.6 degrees and 8.8 degrees by 2100, depending on the amount and rate of pollution spewed into the atmosphere, according to the report.

Those climbing temperatures could cause 6,700 to 11,300 more heat-related deaths annually in California by midcentury, the assessment found. Such fatalities will dominate economic damage to the state from climate change, costing up to $50 billion a year by midcentury.

Scientists have long projected more intense and longer-lasting heat waves by midcentury but have observed those changes occurring faster than anticipated.

“Something that used to happen every 10 years is happening every year,” said Rupa Basu, chief of air and epidemiology for the state’s Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment.

Adding to the risks, scientists say, are trends toward higher humidity and warmer nights. Such conditions hinder people’s ability to recuperate and raise the likelihood of hospital and emergency room visits for a variety of illnesses, from heat stroke and dehydration to heart attacks, kidney disease, gastrointestinal illness and preterm births.

The report also highlights shortcomings in how authorities classify heat waves and alert the public.

In one study cited in the assessment, researchers identified 19 heat waves that landed more than 11,000 people in the hospital between 1999 and 2000. The National Weather Service issued heat advisories for just six of the events.

That led researchers to devise a new way of identifying heat spells that may fall below established temperature thresholds but pose similar health risks. Such episodes, called heat-health events, are defined not by temperature readings but on the public health effects they cause at the local level, particularly to the elderly, young children and other populations most prone to falling ill or dying from the heat.

Modeling by researchers found those health-threatening heat spells will become a persistent fixture in summer months within a few decades, lasting two weeks longer on average in the Central Valley by midcentury.

More air conditioning could attenuate some of the harm, at least for those who can afford it.

Somewhat counterintuitively, researchers expect the health damage from higher temperatures to be worse in coastal areas with historically milder climates, where people are less acclimated to extreme heat and fewer have air conditioning. Researchers have found heat-related deaths to be less common in hotter, inland regions where more people have air conditioning units in their homes.

Seas rise higher than anticipated

As the ocean continues to warm, California’s coast will face more beach erosion, flooding and storm damage.

Until recently, scientists and state policymakers worked with a projection that sea level rise by the end of this century could amount to about 5.48 feet in California under the worst case scenario. But the latest reports and state policies are now accounting for the extreme possibility that sea level rise could exceed 9 feet.

These broader projections incorporate the potential rapid melting of the West Antarctic ice sheet.

Even if the sea rose 6.56 feet rather than the higher possible extreme now adopted by the state, more than 250,000 residents, $38 billion in property and 1,400 miles of roads along the coast are at risk of flooding during a severe storm in Southern California, according to a study led by the U.S. Geological Survey.

Among the most vulnerable communities:

- San Diego, Coronado, Imperial Beach and National City in San Diego County

- Huntington Beach, Seal Beach and Newport Beach in Orange County

- Long Beach, Los Angeles and Malibu in Los Angeles County

Almost all of those areas are at lower elevation and were built on former marshes, researchers said. San Diego County has the most wetlands prone to permanent flooding, and Ventura County is most prone to flooding of agricultural land.

Sea level projections are often presented at a global scale that’s too abstract, said the researchers, who hope their localized projections help the public better understand what’s really at stake when it comes to critical roadways and utilities, businesses and high-value properties.

“It highlights the urgency to act now and to manage the coast appropriately,” said Patrick Barnard, research director of the USGS Climate Impacts and Coastal Processes Team and a co-author of the study.

One such response is the creation of natural shoreline infrastructure, such as vegetated dunes, native oyster reefs or seagrass beds that help buffer wave action and hold back the encroaching sea, according to a report led by the Nature Conservancy.

At Surfers Point in Ventura County, officials turned an eroding parking lot and collapsing bike path into a cobble beach backed by vegetated dune. It has fended off erosion, widened the beach and become the most visited beach in Ventura County, the report said. During high wave conditions in the winter of 2015-16, no damage occurred at the project site: Wave run-up reached the bike path only where dunes were absent.

Other parts of the local shorelines were not so lucky: Ventura Pier was damaged in the storm and the Pierpoint neighborhood suffered inundation, the report said.

Water supply shifting

Northern California — the source of much of the state’s water supply — is likely to grow a bit wetter with climate change. But global warming will alter the timing and form of precipitation, making it tougher for the state to hold on to it.

Warmer temperatures mean mountains will get less snow and more rain and the state snowpack — nature’s reservoir — will melt earlier. That will shorten the season of high stream flows, giving water managers less time to capture the additional water.

Rising sea levels also will increase salinity levels in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, the state’s main transfer point for Northern California supplies headed south. As a result, more freshwater must move through the delta to maintain water quality. And higher temperatures will drive up agricultural water use north of the delta.

Taken together, those effects could reduce delta exports to San Joaquin Valley agriculture and Southland cities by 10% by 2060, researchers found. The amount of water stored in key Northern California reservoirs at the end of the summer season could decline by a quarter.

“The good news is that we may have the same amount of water. But it may come in a different form and a different time,” said John Andrew, assistant deputy director of the Department of Water Resources. “We’re going to have to be a much better manager of the resource.”

The water world has proposed various responses to expected shifts in California’s hydrology.

Those include modifying reservoir operating rules to allow dam managers to hold on to peak winter flows, which they must now sometimes release to create space for spring snowmelt. Floodwater could be used to recharge the San Joaquin Valley’s over-pumped groundwater basins. Existing reservoirs could be expanded and new ones built.

Southern California water agencies want to construct two massive tunnels under the delta to divert high flows from the Sacramento River and transport them to pumping operations that send supplies south. Water districts are also moving to develop more local resources, such as recycled water.

“Everybody has their favorite solution,” Andrew said. “[But] there is no favorite solution. It’s all of them in some amount.”

The study found that computer modeling showed a wetting trend in Northern California and part of Central California, while most of Central California and Southern California would experience a drying trend by 2060.

Another study released as part of the climate assessment found that, on average, annual precipitation was expected to increase in most parts of the state but that the projected changes were small compared to natural variability — California’s year-to-year precipitation levels swing up and down more than any other state in the lower 48.

More destructive wildfires

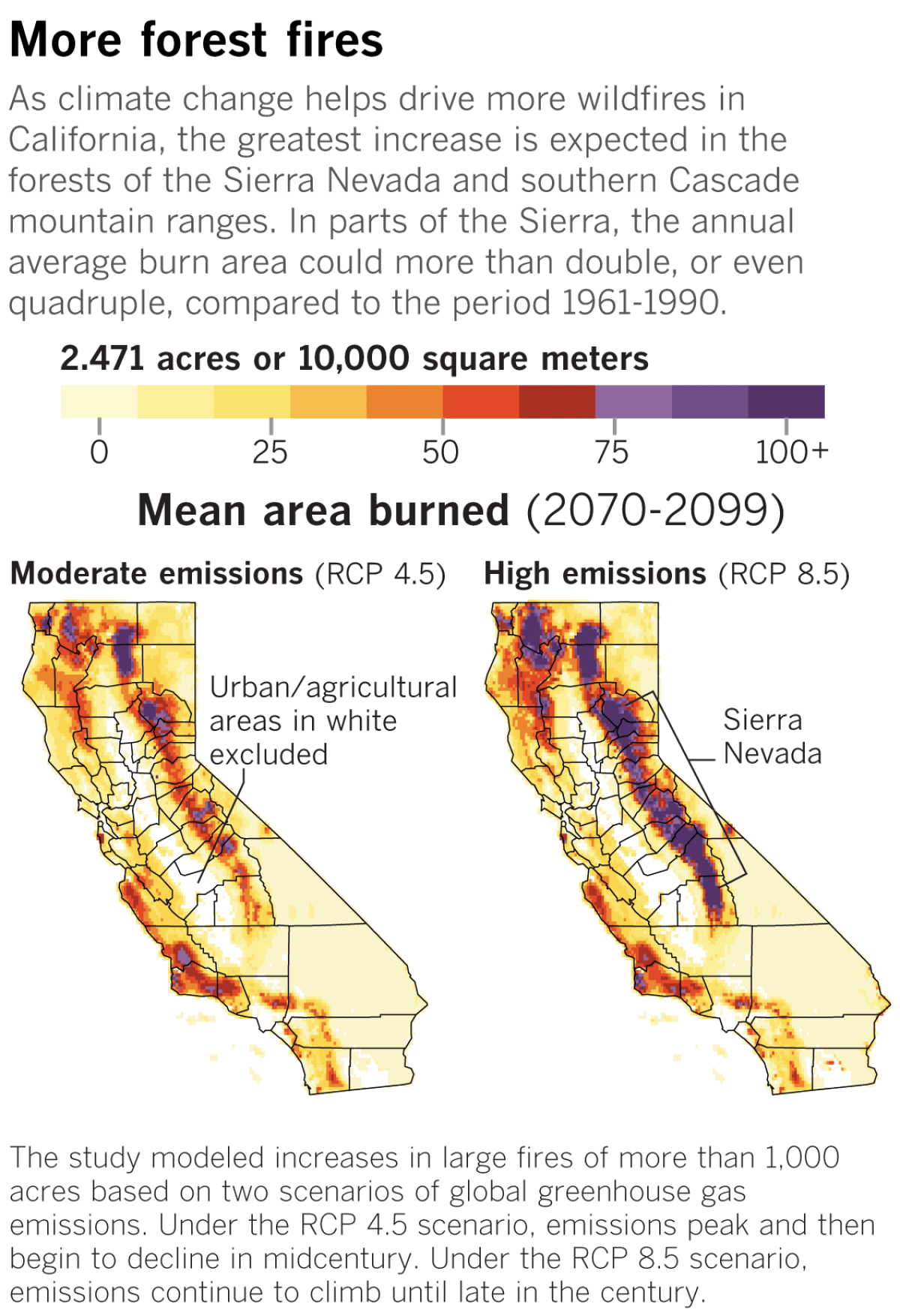

As rising temperatures drive more wildfire in California, the greatest increase is expected in the forests of the Sierra Nevada and southern Cascade mountain ranges.

Forest area burned every year could more than double by the end of the century, according to research by UC Merced professor Anthony Westerling.

Climate change will have more of a wildfire effect in mountain forests in the northern two-thirds of the state than in other parts of fire-prone California because those regions are cooler and moister. When mountain regions grow hotter, soil and vegetation dries out more quickly in the summer, fostering conditions conducive to the spread of wildfire.

Westerling modeled increases in fires of more than 1,000 acres based on two scenarios of global greenhouse gas emissions. Under one scenario, emissions peak and then begin to decline in midcentury. In the second, they continue to climb until late in the century. Under the first scenario, annual average burned forest in much of the Sierra increased by 48% by midcentury and by 120% by century’s end. Under the higher emissions scenario, burned area could surge by as much as 400% by century’s end.

In recent years, bark-beetle infestations killed more than 100 million drought-stressed trees in California. But contrary to conventional wisdom, the study found that in the near term, those dead trees would not significantly increase wildfire.

Westerling cited two reasons for that. When dead needles fall from trees within a few years of a fire, the risk of them fueling an intense blaze drops. And while the dieback is extensive, it is patchy and intermixed with green trees.

Decades from now, when beetle-killed trees fall, the heavy fuel load of downed logs and limbs could increase the risk of mass fires. But Westerling said the effects can’t be quantified because there is no historical analogue on which to base the models.

More air conditioning, but lower gas bills

Rising temperatures will increase demand for electricity across the state as more people install and use air conditioners — even in coastal areas where people have traditionally gone without them.

“If San Francisco with its pleasant coastal climate gets Fresno’s hot climate by end of century, even cool San Franciscans will install window units in existing apartments and new construction will be built with central air conditioning,” according to one study included in the state’s climate assessment.

UC Berkeley environmental economics professor Max Auffhammer, who authored the study that analyzed utility bills for households across the state, found a silver lining: increased electricity demand will be more than offset by reductions in natural gas use for heating as a result of milder winters.

“Electricity consumption is going to go up in the summer,” he said. “But it looks like climate change is going to save many California consumers a bunch of money on their heating bills in the winter.”

More air conditioning will place added strain on the electrical grid by increasing peak demand. To avoid blackouts, utilities will have to make costly upgrades, such as additional generating capacity, substations and energy storage facilities, to meet demand during hot months.

State energy officials said the assessment underscores the urgent need not only for swift global reductions in greenhouse gas emissions but also local actions to protect California from warming that’s already threatening people, natural resources and infrastructure.

“We’re seeing that in the fire situation, we’re seeing that in sea level rise, we’re seeing that in heat spells, in declining snowpack,” said California Energy Commission Chairman Robert Weisenmiller. “The climate is changing now so we need to be adapting our communities.”

Read the state’s summary of the assessment »

Twitter: @tonybarboza

Twitter: @RosannaXia

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.