Fiesta Broadway lives on as the street slowly loses its Latino heart

A generation ago, when organizers chose Broadway for their Fiesta Broadway, the street was the bustling, throbbing heart of a Latino shopping district.

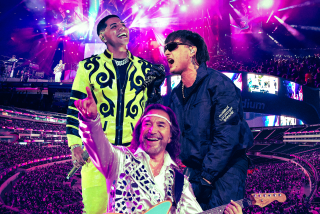

The festival featured artists such as the late ranchera singer Lola Beltran, salsa king Willy Chirino and mariachis, whose songs could be the daily soundtrack of a downtown Los Angeles brought to life by Mexican and Central American immigrants.

Twenty-seven years later, Fiesta Broadway will once again rev up Sunday. But the Latino shoppers and store owners who once claimed a vital stake in it will be a diminished presence.

Few places in downtown Los Angeles have changed as quickly and profoundly as the Broadway corridor. The strip of businesses, grand movie theaters and office buildings has for more than a century been the commercial heart of the city center.

But when downtown fell on hard times after World War II, Broadway was transformed as a different kind of bustling business district, one serving the swelling immigrant population flowing into Los Angeles from Latin American beginning in the late 1970s.

In its heyday in the 1980s, Broadway’s storefronts boomed with businesses catering to immigrants, with rents rivaling those of Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills.

Not anymore.

From his desk in La Catedral de Los Angeles Wedding Chapel, Victor Gonzalez watched as, year to year, Broadway changed. Across the street, he points to a shuttered store that sold bridal and quinceañera dresses. A marquee sign for a once-crowded clothing store that once spelled out the name “Victor” reveals only the fading “i,” “c,” and “t” on one side.

“Downtown was once made up of Latinos,” Gonzalez said. “But everything changes.”

See more of our top stories on Facebook >>

Over the last decade, Broadway and the rest of downtown has seen a wave of gentrification that has brought in upscale lofts, restaurants, boutiques and attractions. Many of the old Latino businesses have been replaced by shops that serve a new generation of more upscale downtown dwellers. Several of the old movie palaces have been restored, including one that serves as an Urban Outfitters store and another that is part of the trendy Ace Hotel.

But the decline of Latino Broadway is about more than gentrification. The district has suffered for several years as immigrants moved out of the central city and into suburban areas. At the same time, other shopping areas that target Latinos opened around the region, providing tough competition for Broadway.

“It’s all these different elements that are creating a perfect storm for ... decline,” said James Rojas, an urban planner.

In the chapel, where Gonzalez has worked for about 18 years, business is down.

He said he believes downtown wants to cater more to young millennials, regardless of their ethnicities or race. The grown children of immigrants don’t necessarily flock to Latino-centric businesses. But there seems to be more white people now than there were even 10 years ago, Gonzalez said, as three white men wearing oversized sunglasses peered curiously through the windows of the chapel before walking on.

“If I put a Starbucks here, it would be filled with people,” Gonzalez declared. “The line would be out the door.”

And so Fiesta Broadway, which began in 1990, beats on, even as the street that gave the festival its name hums evermore to a different tune.

Merchant Arnoldo Dheming said business has dropped dramatically. Ten years ago, he would do 20 to 25 weddings a month in Elvira’s Wedding Chapel, tucked inside a building on Broadway. Now, he does three or four in a month. It isn’t a service that appeals to non-Latinos, he said.

“We are going through a storm,” said Dheming, who has worked in his space for 25 years. “We’re surviving, but it’s not like before.”

In the building where Dheming works, all that’s left of another business, Belinda’s Bridal & Tuxedo, is a yellow sign discarded on the floor. A photography studio took the store’s place, he said.

It makes me feel resentful, that people who fought their whole life, worked ... now have nothing. How do you think we feel?

— Arnoldo Dheming, a merchant

“It makes me feel resentful, that people who fought their whole life, worked ... now have nothing,” Dheming said. “How do you think we feel?”

Many point to Grand Central Market as the prime example of the changes sweeping Broadway. As Letty Maltez walks along the street, she stops outside the market, feet away from a sign advertising a “1 day juice hybrid cleanse” for $30. The market is teeming with a younger, hipper crowd than in the past.

She noted that many of the Latino businesses she remembered from a decade ago have closed. In Grand Central, she used to shop for vegetables and meat at lower prices.

“Now they’ve taken everything and they’re evolving in a way that’s not good for Latinos,” she said. “It’s sad. A lot of people have ended up without jobs.”

The market changed around Ruben Yepez, who has owned the Valeria’s Chiles Spices stall for 27 years. Before, he said, there weren’t a lot of restaurants, but there were many fruit and vegetable stalls.

But now, the number of Latino produce vendors has shrunk, prices have increased and businesses include a juice bar and a butcher shop that sells organic, grass-fed meats.

In many ways the market looks nicer, Yepez said, but he said his customer base seems to decrease with every passing year.

“I think before, for us, it was better,” Yepez said. “Latinos came more and rent was cheaper.”

A quick walk from the market sits Farmacia Million Dollar, a botánica where owner Richard Blitz had previously blamed a drop in business on gentrification. The store is now closed; the lease ended earlier this year.

Estela Gil sits in her chair across the street from Grand Central Market, hoping to sell a few purses and hats in the space she rents in front of a bridal and tuxedo store. Gil knows by now to bring lunch from home — she can’t afford market fare.

On a recent Thursday, she made only $9 in six hours. Years ago, she would make close to $100 in a day.

“No se gana ni pa el café,” Gil said. “You don’t even make enough for a coffee.”

When she thinks about the future of her business, she doesn’t hesitate to answer: There isn’t one.

Maria Fabila, who owns The Black Tie Tuxedo, benefits from Gil renting a space because it helps offset the cost of rent. Fabila opened on Broadway in 1985, left seven year later and returned in 2009. She has watched Latino businesses disappear and Latino customers, especially immigrants, come in fewer numbers as a result.

Hispanics don’t feel like they did before, like they have a place where they can identify with the businesses, with their people. The Hispanic businesses aren’t here anymore.

— Maria Fabila, owner of The Black Tie Tuxedo

“Hispanics don’t feel like they did before, like they have a place where they can identify with the businesses, with their people,” Fabila said. “The Hispanic businesses aren’t here anymore.”

So with this Sunday’s Fiesta Broadway, sprinkled in among the festivities might be a little bitterness.

Unlike in the past, a more abbreviated stretch of Broadway, from Temple to First, will host the festival this year because of Metro subway construction along the street, said Peter Bellas, owner and founder of Fiesta Broadway. In its first year, Fiesta Broadway stretched all the way to Olympic.

------------

FOR THE RECORD

April 25, 10:10 a.m.: This article refers to Peter Bellas as the owner and founder of Fiesta Broadway. Bellas is president and founder of All Access Entertainment, which organizes Fiesta Broadway.

------------

Bellas said Broadway has had positive changes, adding that he’s “seen it cleaned up, seen the area definitely be more safe.”

For longtime Fiesta Broadway attendees, it will be hard to miss how different the area has become.

“Everything is changing ... I don’t know if people see it or not or they just close their eyes,” said Roosevelt Hernandez, who owns Home of the Original Shrimp Place food court on Broadway. A new owner took over Hernandez’s building last year. He doesn’t know what the future holds for his food court.

“Little by little, everybody is getting pushed out,” he said.

ALSO

The most influential person on the coastal commission may be this lobbyist

The Armenian genocide: Glendale celebrates a small step in the fight for recognition

Looking for answers but getting sandbagged about billionaire’s Martins Beach property

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.