A new beginning for MLK hospital and the community

For several decades, King/Drew hospital in South Los Angeles served one of the neediest parts of Los Angeles, treating patients who didn’t have insurance or anywhere else to turn for care.

Its opening in 1972 was viewed as a victory of the civil rights era and a source of pride for black Los Angeles. But plagued in later years by poor medical care, staff errors and a series of controversial patient deaths, it came to be viewed by many as a place of peril, nicknamed Killer King.

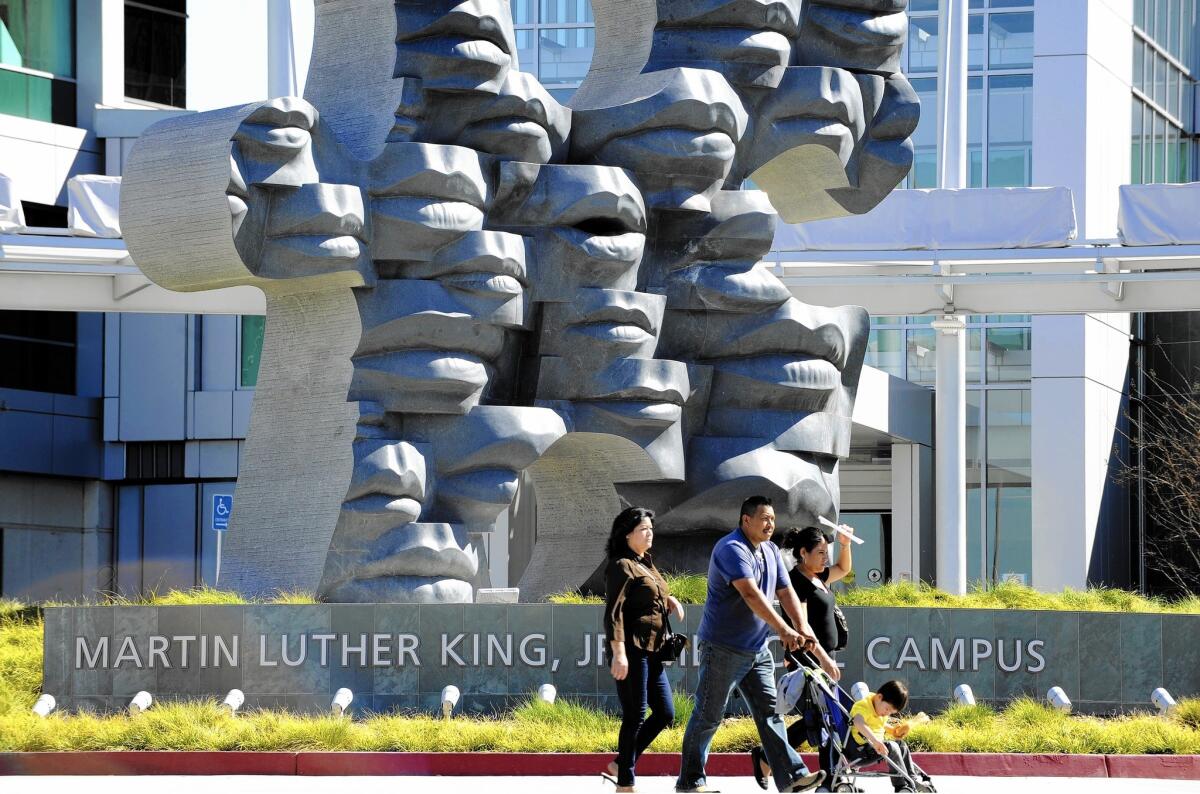

On Tuesday, delivering on a long-delayed promise to replace the facility, officials will open the doors on the new, state-of-the-art Martin Luther King, Jr. Community Hospital. It shares the site of the original medical center, but it has a new management structure and operating philosophy as it enters a dramatically different healthcare landscape than the one exited by its predecessor.

At about one-third the size of the old medical center, the 131-bed MLK Community Hospital will emphasize the tenets of the recent healthcare system overhaul under Obamacare, focusing on preventive care to reduce the need for emergency room visits and hospitalization. And unlike the old hospital that was run by an arm of the huge L.A. County government bureaucracy, the new hospital will be managed by a special governing authority overseen by healthcare, business and law professionals focused solely on the facility.

“It really is a new beginning with new people,” said Dr. Oscar Casillas, the hospital’s director of emergency medicine. “The only thing that’s the same is our physical location.”

Though the downsizing of the facility has drawn some criticism, health experts say that the new hospital aligns with the latest thinking in healthcare, particularly for underserved urban communities.

Its design dovetails with the Affordable Care Act and supports the idea that hospitals and emergency rooms should be healthcare options of last resort, instead of default treatment centers for basic care and unattended maladies.

MLK Community Hospital is flanked by an expanded outpatient clinic, a new urgent-care psychiatric center and a new public health clinic, where patients can get STD testing, immunizations and other preventive care.

Jennifer Bayer, a vice president with the Hospital Assn. of Southern California, said the campus is a model for the direction healthcare is taking as patients use hospitals less and less.

According to state data, the number of patients admitted to California hospitals from 2008 to 2012 declined, as did the average length of stays and the occupancy rate.

Still, given the needs in the surrounding community, which has high rates of chronic disease and relatively few doctors and specialists, Bayer said she thinks South L.A. might still need additional hospital beds in the short term, as the healthcare system makes the transition to more robust preventive care.

“Time will say,” she said.

One of the most immediate challenges for the hospital will be distancing itself from the past and rebuilding the best parts of the old hospital’s relationship with area residents.

Despite King/Drew’s problems, many in the community were upset when the federal government pulled the facility’s funding, forcing it to shut down in 2007.

Watts resident Mary Brooks had hip surgery there in 2003, and remembers laying in a pool of her own blood for hours while she was in recovery. Still, she said the hospital generally took good care of her, and when it closed, she worried it would never reopen.

“I felt like ‘Where are we going to go?,” said the 64-year-old. Earlier this year, Brooks slipped in her home and had to wait seven hours at a nearby emergency room for treatment, she said.

She said she’s looking forward to the opening of MLK Community Hospital.

“King got everything for me right here,” she said.

Hospital administrators say they’ve made hiring experienced, well-qualified staff a priority. Dr. Elaine Batchlor, who was previously chief medical officer of LA Care Health Plan, serves as chief executive, and Dr. John Fisher, who was most recently working at Kern Health Systems, serves as chief medical officer.

So far, 130 physicians, many of whom also work at UCLA medical facilities, have been approved to work at the hospital, Fisher said. He said administrators have carefully vetted all hospital staff and don’t expect a return of the kinds of complaints that gave King/Drew its reputation. “It all goes back to the fact that this is a brand new hospital,” he said.

Some critics of the old medical center have long-held memories of its failures, even as they hold out hope for the new MLK Community Hospital. Robert Winter, 54, of Downey said he was treated twice at King/Drew and he couldn’t wait to get out. Doctors left a bullet hole wound open when he was rushed there by ambulance in the 1986, he said, and he was overmedicated when he arrived there with chest pain in 1995.

“It was a madhouse,” Winter said. “The hospital was a cesspool because of the people who ran it.”

But Winter said he’s checked the backgrounds of the new hospital administration and toured the facility. He was surprised at the friendliness of the guards, custodians and medical workers.

“They have to overcome the prior reputation,” he said. “But I think they can do it.”

Dr. Mark Ghaly, who oversees the larger MLK medical campus for the county’s Department of Health Services, said, “What was lost in the old hospital has been won back. For a community that loses so much and deals with so much … this is a victory.”

Follow @skarlamangla and @angeljennings for more L.A. news.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.