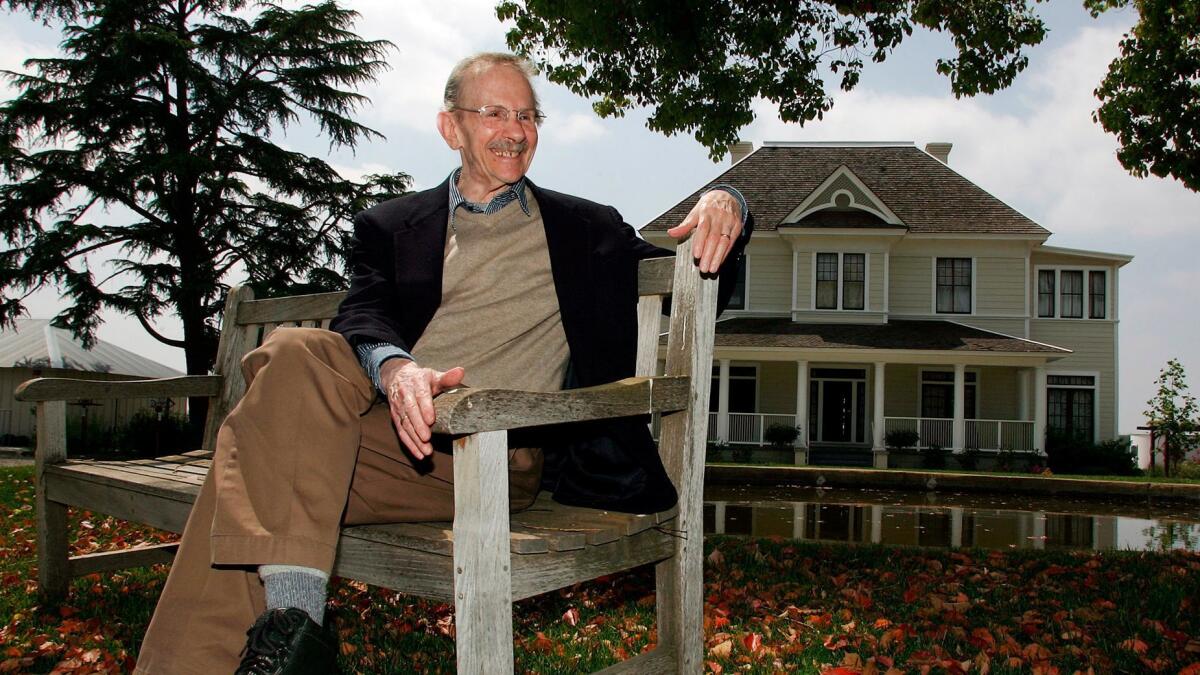

Poet Philip Levine sketched the life of working-class Americans

In the spring of 1952, poet Philip Levine worked at the Chevrolet Gear and Axle plant in Detroit, Mich. He was 24 and had been writing poems for nearly 10 years.

Some get their calling early, but being a young poet is not easy. He had clocked hours in an ice factory, a bottling corporation, on the railroad — but none as boring and hazardous as in the gear and axle plant, where he pulled automotive parts from the forge and hung them on conveyors that whisked them elsewhere in the factory.

Years later, well committed to a life of “poverty and poetry,” he could still feel “almost without hatred that old sense of utter weariness that descended each night from my neck to my shoulders, and then down my arms to my wrists and hands.”

Over his lifetime, Levine, who died at 87 in 2015, never lost that muscle memory, his ars poetica. He carried it with him whenever he “lifted a pencil to write,” the memory of that hellish world — with its clanging steel, poisoned rats and freezing winds rushing through broken windows — of so many exploited lives.

Exploited was Levine’s word, taken from a 1972 interview, and today it sounds almost antiquarian, a throwback to a time and place when such language was valued for its ability to sharpen class distinctions. Almost 50 years later, the words are more passive, couched in phrases like wage stagnation and widening inequality, as if that were the status quo.

But Levine never acquiesced; his leftward leanings were softened only by his sense of justice and compassion. Russian-Jewish immigrant parents, a Depression childhood, the race riots and labor battles of the 1940s demanded nothing less.

He was a poet who had journeyed from Michigan to California, where he taught at Cal State Fresno, who drew upon the lessons of teachers (John Berryman) and his readings (the poets of Republican Spain) and found his voice, “that could speak of all the things I would never have dared share with anyone, a voice that tried to consider the value of being alive.”

I think the writing of a poem is a political act.

— Philip Levine

As he gazed upon America with unflinching ferocity, he often dared his readers to walk with him down the ruined streets of Detroit to meet the survivors, the workers, those who struggled for so long to find work and meaning in their lives and had to accept it on someone else’s terms.

As he wrote in his seminal poem, “What Work Is”:

We stand in the rain in a long line

waiting at Ford Highland Park. For work.

You know what work is — if you’re

old enough to read this you know what

work is, although you may not do it.

Forget you. This is about waiting,

shifting from one foot to another.

In some 20 books of poetry, he mined this past — that tensing muscle — to create a body of work as demanding as it was lyrically entrancing. His voice modulated from the anger of his celebrated “They Feed They Lion” of 1968 to his later-year elegies, like the title poem of his 1994 Pulitzer Prize-winning collection, “The Simple Truth”:

Some things

you know all your life. They are so simple and true

they must be said without elegance, meter and rhyme,

they must be laid on the table beside the salt shaker,

the glass of water, the absence of light gathering

in the shadows of picture frames, they must be

naked and alone, they must stand for themselves.

Simplicity — in language, structure and imagery — was the hallmark of his final volumes, not the least, his most recent, the posthumous “The Last Shift,” published concurrently with a selection of prose, “My Lost Poets: A Life in Poetry.”

This gathering of his work, curated by his friend, literary executor and poet Edward Hirsch, comes at a needed time when the American identity, especially the working class identity, seems to have disappeared, no longer visible beneath traditional banners of party politics and Democratic loyalties.

But Levine’s poems — with their pictures of the industrial Midwest animated by despair, yearning and love — suggest a more troubling truth. The working class has always been hard to see because seeing would mean confronting the struggle of their lives, a struggle of race, inequity and inequality.

“I think the writing of a poem is a political act,” Levine told an interviewer in 1974. “The sources of anger are frequently social, and they have to do with the fact that people’s lives are frustrated, they’re lied to, they’re cheated, that there is no equitable handing out of the goods of this world.”

More than 40 years later, his aesthetic — indignation for the squandered opportunities of this republic — hadn’t changed. In “The Last Shift,” this final poem of this final volume, he describes being caught in traffic on his way to work, 7:30 in the morning, and the world rises up around him like a dream.

Men keep warm by a fire “made from fence posts and garage doors.” Police sit in their car eating sugar doughnuts “as delicately as two elderly women,” and children descend from dark houses, “gloved and scarved, on their way to school.”

The images, however, are haunted by emblems of their impermanence. Beside him stands a two-storied house “all of its / rooms torn into view, its connections / and tubing gone, the furniture gone, / the floors ripped up for firewood.”

As much as America has changed — neighborhoods cleared, factories torn down, the unwinding as George Packer has called it — Levine could see that the nation’s character, for better and worse, has endured, which is why memory, the font for so much of his poetry, seldom seems dated.

The great movements of our lives go on, he once explained: “We grow, we love, we believe, we open our hearts, we close our doors, we give birth, we kill others, we kill ourselves, we embrace each other.”

The poems in “The Last Shift” offer a familiar glimpse of Levine’s past, which became over time less of a grip than an embrace. In “Urban Myths,” he writes:

I still go back each year to Detroit

to relive my long childhood in the houses

that burned down ages ago, to walk alone

the streets paved with gold ….

Levine, who was appointed U.S. poet laureate in 2011, has been criticized by some for being too romantic in his reveries, but he was a writer who looked to the world — “utterly unknowable, utterly unacceptable, utterly unlovable” — to calibrate his emotions.

He once proclaimed that he wanted “to be a poet of joy as well as suffering,” and his greatest joy comes in the beauty — and the attendant mystery — of daily life. A poem, he once said, is not a gimmick, a formula. A poem “is a new beginning, and often — as Keats knew as a boy wonder — you have to sit with your wings furled and wait for a moment to fly.”

In waiting, Levine found his humility. From the poem “Godspell”:

About life I can say nothing. Instead,

half-blind, I wander the woods while

a west wind picks up in the trees

clustered above. The pines make

a music like no other, rising and

falling like a distant surf at night

that calms the darkness before

first light. How weightless

words are when nothing will do.

In “Getting and Spending,” a marvelous essay from “My Lost Poets,” Levine writes — as if in response to those critics — “we lose what is most precious in the act of saving oneself from the expenditure of feeling and the uncertainty involved in risking the self.”

Never stingy, Levine left nothing behind. He knew there was plenty to go around of what really mattered.

Philip Levine

Alfred A. Knopf: 96 pp., $26.95

::

“My Lost Poets: A Life in Poetry”

Philip Levine

Alfred A. Knopf: 224 pp., $26.95

Twitter: @tcurwen

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.