If you think the war on drugs is a miserable failure, you should vote to legalize pot

Bryan Rosenthal is hardly the kind of guy you’d expect to get caught up in the war on drugs. He describes himself as “a rich white kid from Encino,” whose father worked for junk bond king Michael Milken.

Rosenthal, now 43, discovered the calming properties of marijuana at an early age.

In his 20s, he started growing his own. He was living in West Hollywood, cultivating marijuana plants in his garage when an acquaintance, for reasons he has never figured out, called the police and reported that Rosenthal was growing pot, making meth and had guns.

“They sent fire trucks and six cop cars to my house because of what they thought was going to be there,” he told me Thursday afternoon from his home in Vallejo. “There were no guns and no meth lab. It was just me growing pot.”

He was charged with cultivating more than a pound of marijuana, a felony, and his father bailed him out of jail. Not everyone who gets arrested for pot is so lucky.

In a deal with prosecutors, Rosenthal got three years of probation, community service, and a fine — but no jail time.

As part of the deal, he was also required to give a DNA sample and register as a drug offender. He thought he’d accomplished both tasks when he gave his DNA.

Big mistake.

::

If the Adult Use of Marijuana Act passes Tuesday, it will do many things.

Mainly — and most important to people who are sick of wasting public dollars fighting a hopeless battle against a substance that is used by millions of Californians — it will legalize and regulate marijuana.

Anyone 21 and older will be allowed to possess, transport, purchase, consume and share up to an ounce of marijuana, or eight grams of the concentrates that are used in vape pens.

Adults 21 and older will also be able to grow up to six pot plants at home, away from public view.

As its proponents like to say, if Proposition 64 passes, marijuana will no longer be a gateway drug … to the criminal justice system.

People younger than 18 who are caught with pot will not be hit with infractions and fines. They will instead be routed to drug education and community service.

The law reduces many felonies (such as selling marijuana and possession with intent to sell) to misdemeanors. Two felonies will remain on the books: selling marijuana to minors and chemically manufacturing cannabis concentrates without a license, a dangerous practice that involves explosive chemicals.

In a post-legalization California, as much as a billion dollars will flow into the state, and indirectly, to counties and cities. The money will be used, first, to enforce the law.

The rest will be used to promote medical cannabis research at UC San Diego, to help the California Highway Patrol develop stoned driving standards, to create jobs in communities hit hardest by the war on drugs, to pay for the restoration of public lands damaged by illegal marijuana grows and to fund youth drug education and after-school programs.

Over the last few months, I’ve told you about Mendocino pot growers who have mixed feelings about the changes that legalization might bring (especially lower prices), about the harm pot can do to undeveloped brains and about how officials up and down the state are dealing with the coming cannabis revolution.

But the most worthy goal of this initiative may well be the undoing of damage that marijuana prohibition has inflicted on thousands of Californians, people like Rosenthal, who have become tangled in a criminal justice system that sometimes treats rapists more tenderly than pot smokers.

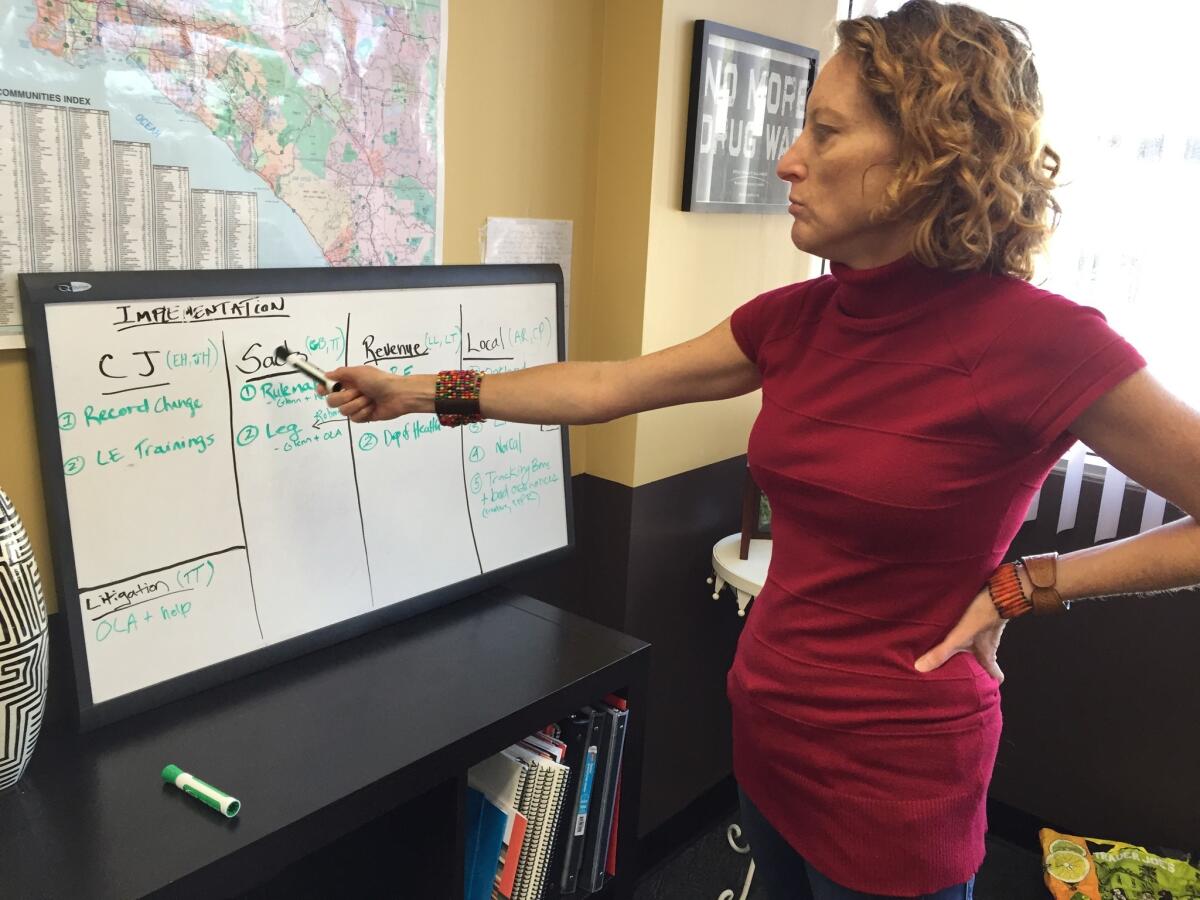

“This will prevent thousands of arrests a year,” said Lynne Lyman, California director of Drug Policy Alliance, a major backer of Proposition 64. “Between 2005 and 2014, California averaged 14,000 felony arrests a year for marijuana. That doesn’t include misdemeanors.”

This is especially important for people of color, who are disproportionately arrested and convicted for marijuana crimes.

Anyone convicted of a crime that is either reduced or eliminated under Proposition 64 will be eligible to apply for resentencing or expungement, which will erase convictions entirely. That is true for people serving time now, and for those, like Rosenthal, who have already completed their sentences.

No other state marijuana initiative, Lyman said, has included such a provision.

::

Nine months after Rosenthal’s legal case was settled, he was in Northern California, selling San Francisco Chronicle subscriptions, trying to get back on his feet. To save for an apartment, he rented a week-to-week motel room in Millbrae. He did not know that police at that time had the right to check motel registers, looking for people with outstanding warrants.

Nor did he realize that there was a warrant out for his arrest in Los Angeles, for failing to register as a drug offender.

One night after he was done with work, five Millbrae police officers knocked on his door with a warrant for his arrest. “I hadn’t registered as a drug offender,” he said. “It was a no-bail probation violation warrant.”

He spent three days in San Mateo County Jail, then was transferred to L.A. County Jail, where he waited for a probation report required by the court, which was supposed to take five days. But it was Christmastime, and the holidays slowed everything down. “I was in L.A. County Jail for 27 days,” he said. “It was the biggest nightmare of my life.”

When he finally appeared in court, he agreed to spend three months in drug rehab. “I was with meth addicts, heroin addicts,” he said. “A kid I got close to OD’d while I was there.”

Later, he ended up with a temporary job at Ameriprise Financial. It turned into a permanent job, and he thought, “I can’t believe I have turned my life around.” But when the firm did a background check, his felony conviction popped up. He was told to leave without returning to his desk.

He landed a new sales job and flourished. He founded a foundation, Cann-I-Dream, which raises money from the cannabis industry to help sick children get access to medical marijuana. But he still has that felony conviction on his record.

If Proposition 64 passes, Rosenthal will apply for expungement as soon as he can.

“I run a children’s charity,” he said, “and my credibility goes up dramatically when I don’t have to say that I have been convicted of a crime.”

California won’t be the first state to legalize marijuana, but it will be the biggest and the most influential.

If you think the war on drugs has caused enough pointless suffering, you should vote for Proposition 64.

Get more of Robin Abcarian’s work and follow her on Twitter @AbcarianLAT

ALSO

Bill Clinton, the natural, reaches out to voters in places that love Trump

These 76-year-old twins have grown pot for decades. Here’s why they oppose legalization

With pot on the ballot, an expert answers questions on stoned driving, Mexican cartels and more