Decades before Black Lives Matter, there were the Black Panthers in Oakland

The corner of Market and 55th streets in Oakland is unremarkable in many ways. Rush hour traffic whizzes by modest homes that have become mostly unaffordable for the working class African Americans who once defined the place.

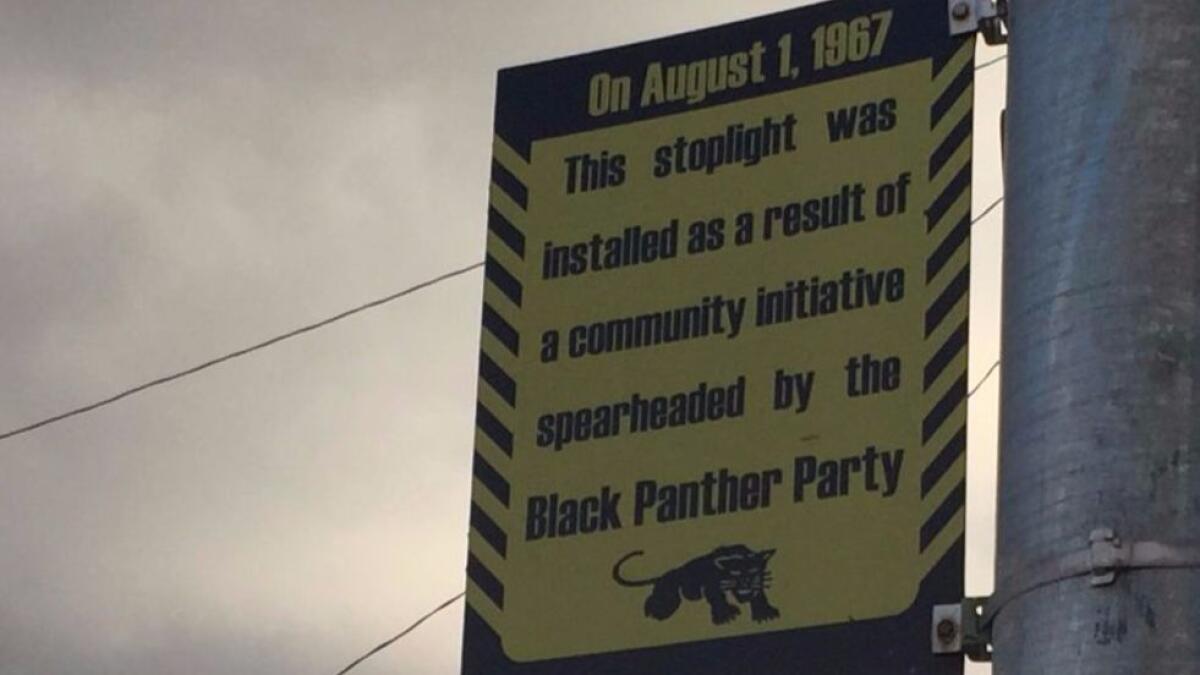

But this intersection holds a unique place in California history. It is the site of the first important social action by the Black Panther Party for Self Defense, the revolutionary black power movement founded 50 years ago by Merritt College students Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale in response to rampant police brutality.

In 1967, after several children from Santa Fe Elementary School were injured crossing the street, local activists and the Black Panthers demanded the city of Oakland install a traffic light. The City Council dragged its feet. The Panthers organized a squadron of rifle-toting crossing guards to get the kids across safely. Oakland relented, and installed a light, well ahead of schedule.

For many Americans, the lasting image of the Black Panther is the armed, black-beret-and-leather-jacket clad radical whose militant quest for racial and political equality fell apart amid FBI provocation and harassment, the killing or relentless persecution of its charismatic leaders (some of whom did indeed engage in indefensible acts of violence), and finally, the crack epidemic, to which Newton fell victim.

Or they might think of the Panthers in purely aesthetic terms; Beyonce borrowed the iconic look, complete with berets and Afros, for her backup singers at the Super Bowl.

If they remember anything at all about what the Panthers accomplished, it is probably the party’s celebrated free breakfast program.

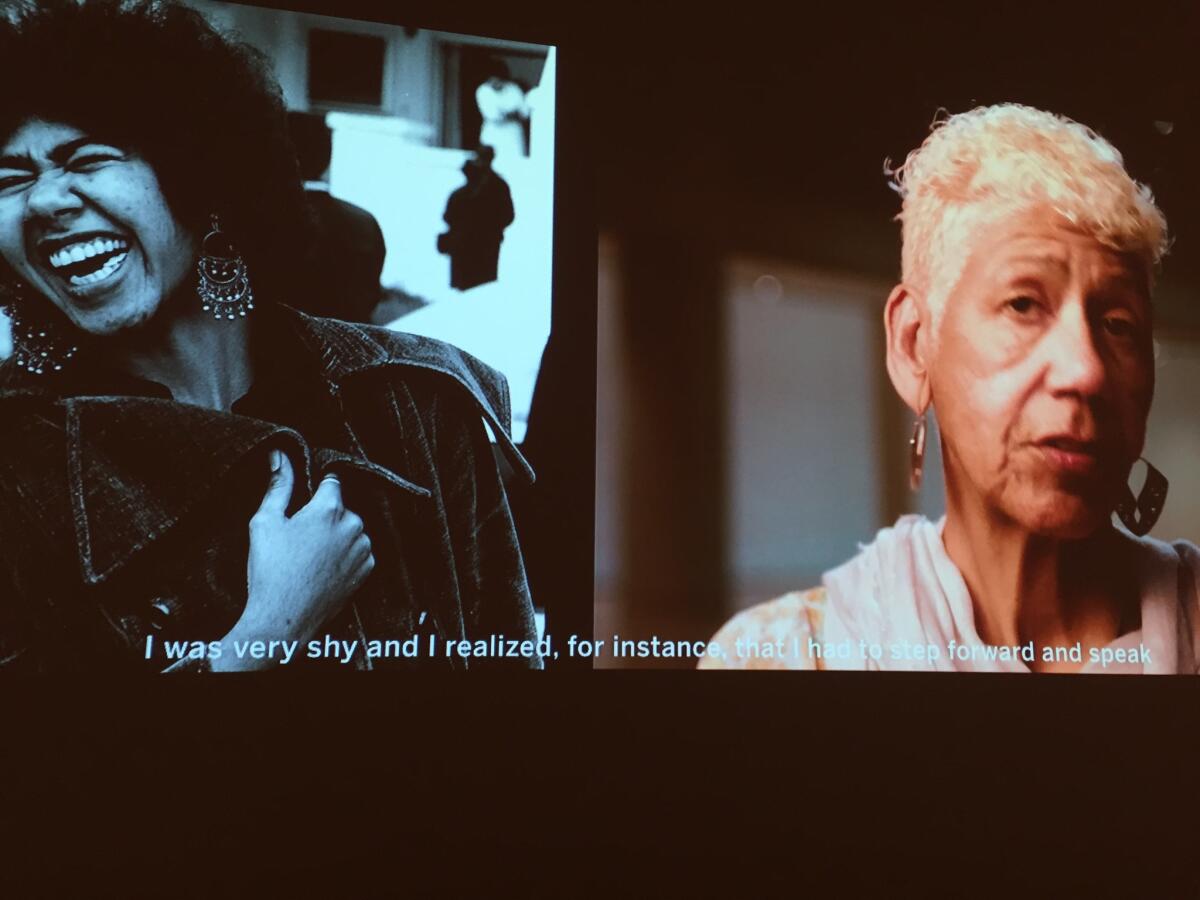

“This is the narrative that has held for many people,” said educator Ericka Huggins, 66, a former Black Panther leader whose 23-year-old husband, John Huggins, was killed at UCLA in 1970 by members of a rival black power group in an incident that she and others believe was orchestrated by the FBI. Huggins, who spent two years in prison on conspiracy charges that were later dropped, became director of the Panther’s groundbreaking Oakland Community School.

“In the last few years,” said Huggins, who lectures widely, “young people have begun to ask: ‘Well, if you had a school, you had free clinics, if you took care of those incarcerated by making sure their families could get on buses and visit them in the faraway places that prisons are, if you cared about the quality of life in the community and created programs to do that, why don’t we know about it?’ ”

Why don’t we know, for instance, that two clinics founded by the Panthers, in Seattle and Portland, still exist?

::

I wandered around North Oakland late Wednesday afternoon, with earbuds, listening to a recorded walking tour of Black Panther history on an app that I downloaded onto my phone. Wry commentary was provided by Davin A. Thompson, an Oakland emcee and arts educator.

Noting that the neighborhood’s gentrification is pushing out its black residents, he says, “Here come the Subarus! White people with kids. Fertilizer for housing prices.”

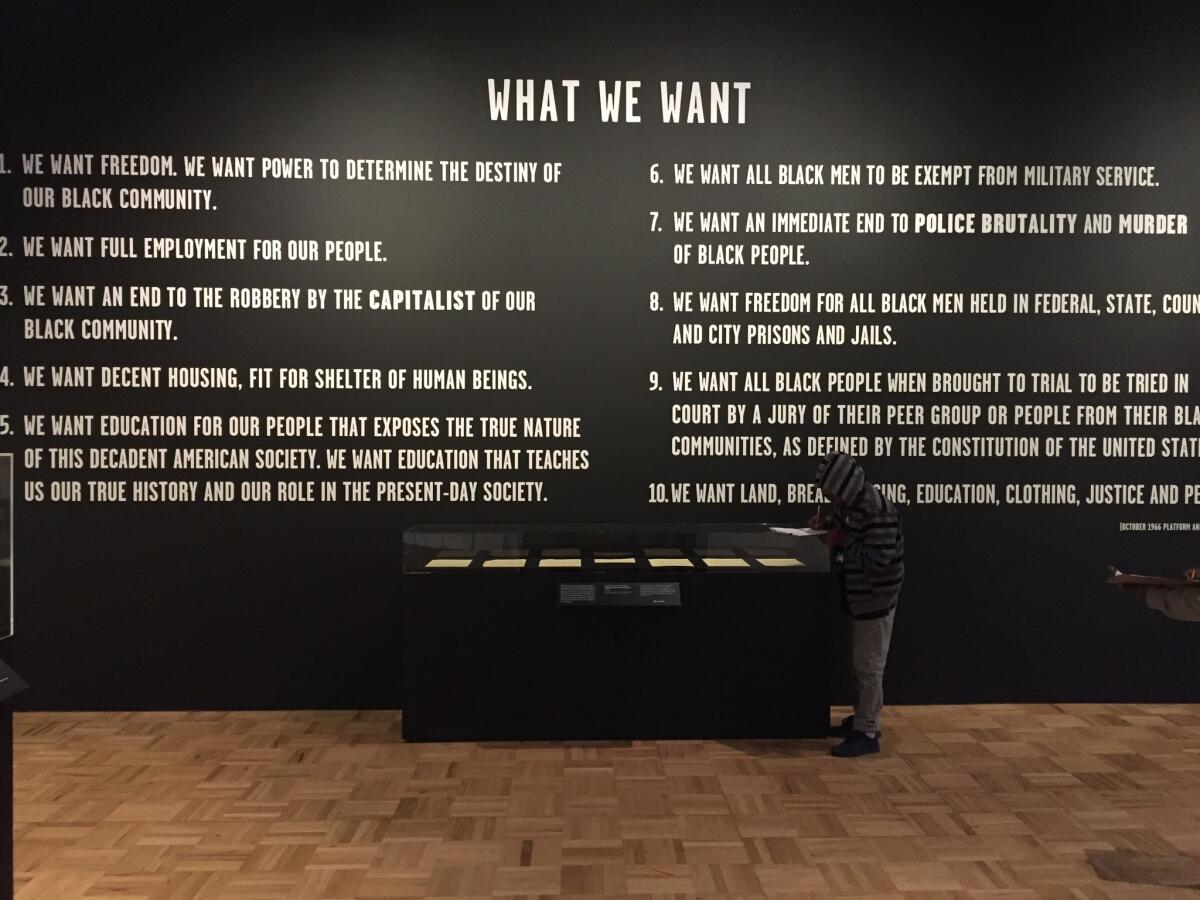

Stops included Bobby Seale’s home, the North Oakland Service Center, where Seale and Newton worked, and came up with their foundational “10-Point Program” manifesto and a small park with a community garden that reflects the spirit of the Panthers’ forgotten social programs. I bought a sweet potato pie at It’s all Good, a bakery now on the site of the Black Panther newspaper’s old offices. That paper’s weekly circulation of 250,000 had provided the party with much of its revenue until the party finally sputtered out in 1982.

The foot tour was an edifying adjunct to the Oakland Museum of California’s powerful exhibit, “All Power to the People: Black Panthers at 50,” which runs through Feb. 12.

The show’s curator, Rene de Guzman, gathered many surviving Panthers, including Huggins, to help shape the exhibit. I wondered how the museum tried to balance the party’s good works with its more troublesome aspects.

“Like everything,” de Guzman said, “it’s complicated. The world was about to explode — the Vietnam War, unrest on campus, unrest at the 1968 Democratic convention. Their intention was good, that is the thing no one can refute. They were young people operating during a really turbulent time. Mistakes were made.”

Visitors are greeted by a bronze replica of the wicker peacock chair from one of the era’s most iconic images: Huey Newton sitting, as if enthroned, holding a spear in one hand and a rifle in the other, like scepters. Schoolboys from Oakland’s African American Male Achievement program took turns sitting in the chair.

“It’s important for them to know they are part of a legacy,” said Oakland High School teacher David Goodlett, 55. “Most of the Panthers were around their age. The narrative has always been misconstrued to make the Panthers one-dimensional when they were feeding the community, getting health care to the community, pushing for political rights, voting participation and educational equity.”

He called over one of his students, 16-year-old Jermaine Robinson, who said he hadn’t thought much about the Black Panthers before. “But now I see what they are fighting for,” he said. “It’s empowering. It makes me want to go out and stand up for our rights.”

::

In Oakland, I learned on my walking tour, the Panthers took full advantage of California’s open carry law. They followed police around, or listened to scanners, then rushed to arrests armed not just with weapons but legal advice.

“Patrolling the police was strictly a tactic,” Seale, 80, told me by phone Thursday. “I wanted to capture the imagination of the people. If I can capture their imagination, I can get them to register to vote, take over the city council, the county seats. That was the whole idea of the Black Panther Party.”

This confrontational style, and the frequent chant “Off the pigs!” so rattled the white establishment that a bill banning Californians from carrying loaded firearms in public soon passed the state Legislature. In protest, Seale took his fledgling band of Panthers to Sacramento. On May 2, 1967, looking for the spectator section, Seale said, they bumbled onto the Assembly floor, with loaded guns. The ensuing notoriety helped make the Black Panthers a household name.

Gov. Ronald Reagan, who would later champion the Second Amendment, signed the bill.

You know who else supported it? The NRA.

So many ironies, such a crazy time.

Twitter: @AbcarianLAT

Headlines got you down? Try hanging out with 700 free-range rescued cats

No joke: A priest, a rabbi and a social scientist consider the election’s emotional fallout