For decades, one of the world’s most unusual and unlikely amusement parks sat forgotten in shipping containers about two hours north of Dallas. Its visitors? Raccoons, some snakes. All the while, the glorious and outlandish rides of the little-known Luna Luna lay preserved and untouched.

Only these were no ordinary attractions.

The creations of Luna Luna were dreamed up by icons of contemporary art — an enchanted forest, for instance, crafted by David Hockney, or a Ferris wheel envisioned by Jean-Michel Basquiat, where the whimsical contrasts with violent images of an exploding house and stark phrases of racial inequality, all placed like graffiti in haste. There’s more, including a celebratory carousel from Keith Haring, where the artist’s curved creatures come alive as toy-like blocks.

These and other hand-crafted amusement park attractions will rise again, this time in Los Angeles. Luna Luna will emerge from purgatory for public viewing this month as part of a multimonth, immersive art exhibition. An exact opening date is still to be determined.

The exhibit, “Luna Luna: Forgotten Fantasy,” is backed by hip-hop artist Drake and his entertainment firm, DreamCrew, and will run through spring 2024, overtaking a sprawling Los Angeles warehouse space on the outskirts of downtown. Los Angeles is a fitting home for Luna Luna, for Southern California birthed the modern amusement park industry in 1955 with the opening of Disneyland, and arguably no other city is more consumed with the merger of art, commerce and entertainment.

Luna Luna — the term “luna park” was synonymous with amusement parks in the early 19th century — had the grand ideals of early Disneyland, in that it could merge the worlds of high and low art into something grandiose. But whereas Disneyland, with some notable exceptions, took its influences from early cinematic and animated works, Luna Luna let all its creators run free.

See, for example, Daniel Spoerri‘s restroom façade, created to mimic an imposing, concrete building, complete with mini towers of steaming excrement. Or a mirrored dome crafted by Salvador Dalí designed to disorient. The large-scale sculptures were welcoming in their humor, inviting in their exaggeration.

Ranking the rides and attractions at Disneyland and California Adventure from best to worst is hard — but not impossible. Here is the ultimate Disneyland ride ranking.

Some of the attractions, such as Hockney’s forest and Dalí‘s dome, are intended to be timed experiences. Others, such as Basquiat’s Ferris wheel, are expected to be operational but not fit for guests. Curators say they likely weren’t up to modern code in 1987, when Luna Luna had a brief summer run in Hamburg, Germany, and most assuredly wouldn’t pass a 2023 inspection. But there is a common thread among the Luna Luna creations. They’re all full of life, color and movement, and they stand as celebrations of the amusement park as communal gathering spaces.

In archival footage of the original Luna Luna shows, for instance, Haring discusses his squiggly and arched shapes as if they are creatures from a fairy tale as he reminisces about a trip to Disneyland. “Luna Luna was special to Keith,” says Gil Vazquez, his friend, and president and executive director of the Keith Haring Foundation..

“Reflecting on his own memories of times at amusement parks I’m sure brought back the magic of childhood that resonated deeply with him,” Vazquez says. “By creating a carousel with his famed figures, he in a sense gets to be Disney. Who doesn’t have great memories associated with state fairs, carnivals and the granddaddy of those, Disneyland?”

)

While Basquiat’s sisters Lisane Basquiat and Jeanine Heriveaux say the family regularly visited New York’s Coney Island as children, they note Luna Luna was still an unexpected art project for their late brother. “Jean-Michel loved play and fun,” says Lisane. “He enjoyed amusement parks and experienced them frequently as a child growing up in New York and, specifically, Brooklyn. Amusement parks were completely on brand for him, albeit an unusual place for him and his friends to collaborate.”

Though visitors won’t be able to hop on Haring’s carousel or Basquiat’s Ferris wheel, Luna Luna will attempt to create some of that carnival feel. Performers will wander the 60,000-square-foot complex, as Luna Luna will be part entertainment event and part historical show that documents how one André Heller created and conceived such a space. Heller’s own work bent toward the surreal, as he often worked with unexpected materials such as inflatables, including a balloon-like house for Luna Luna with multicolored porcupine spikes.

Taken as a whole, Luna Luna will have another mission: to reclaim the amusement park as an art-driven space. Luna Luna will make the argument that amusement and theme parks matter. There’s a reason, after all, Disneyland draws an estimated 17 million people per year, and it’s not solely because we love singing pirates. Amusement parks are a reflection of our culture’s myths and dreams, providing a place not to escape but to play. Luna Luna, like Disneyland, is a stage, a theatrical environment where we are the performers, a place of jubilation in good times and a communal balm in dark ones.

“The luna park is always a dream space,” says Helen Molesworth, Luna Luna’s curatorial adviser and a former chief curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art. “It’s like someone goes around and untightens the screws of your need to behave, your need to be good, your need to be smart, your need to be proper. Someone just untightens those four screws, and you can think different things and feel different things.

“You can tap into whatever it is in you that you locked up, whether it’s your childhood or sense of adventure or desire to be scared or desire to be bamboozled,” Molesworth continues. “Whatever it is you talked yourself out of, this project lets you reengage with.”

“An epicurean view of life”

Luna Luna was ahead of its time. And in some ways it’s a miracle that it existed at all. The contemporary art world is filled with cynical looks at the themed-entertainment industry: Artists have been distorting Mickey Mouse imagery for nearly as long as the animated character has existed, and then, of course, there’s Banksy’s mid-2015 corporate teardown, Dismaland. Luna Luna is not that.

“An amusement park is, after all, mistakenly regarded as something less serious than, say, an exhibition at the Centre Pompidou [in Paris],” said Heller in the 1987 published Luna Luna exhibition book, which has been reissued today by Phaidon.

In 2023, the idea of an art park doesn’t seem so far-fetched. Disneyland, for one, is under constant reassessment, and what is an attraction such as It’s a Small World, designed almost entirely in the visions of artists Mary Blair and Rolly Crump, but a boat ride through a makeshift art gallery? Then there’s Meow Wolf, the Santa Fe, N.M.-based art collective that has opened theme park-inspired walk-through exhibitions in numerous cities, including Las Vegas and, most recently, Grapevine, Texas.

Heller was prescient in his merger of amusement parks and art institutions. “I find this project so interesting because, throughout the history of the 20th century in art, there’s been a dream on the part of artists to break down the boundaries between art and life,” Molesworth says. “This is one of those projects that does it.”

A first look at Meow Wolf’s latest wonderland in Texas, which plants the company’s progressive flag in a red state with a message that art can break barriers.

Heller, whose initial Luna Luna began with a reported $500,000 grant from a German magazine, himself often spoke of trips to Vienna’s Prater amusement park as inspiration, contrasting lasting images of WWII outside its gates with the fantasy that was inside the park — the ventriloquists, trick shooters and tap dancers. “I have basically never stopped spinning the web of these childhood myths, a life-saving assertion of the imagination against the sum of what threatens me and causes me despair,” Heller said in the exhibition monograph.

Luna Luna’s resuscitation became a reality in 2022, when Drake’s entertainment firm DreamCrew acquired the Luna Luna assets for an undisclosed sum from the philanthropic Stephen and Mary Birch Foundation. The project was brought to DreamCrew via creative director Michael Goldberg, who in 2019 says he stumbled across an article about the original park, and then spent the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic becoming increasingly obsessed.

The recently reopened Adventureland Treehouse Inspired by Walt Disney’s Swiss Family Robinson places its focus on old-fashioned theme park trickery.

“When Luna Luna first caught our attention, we knew we needed to be a driving force behind its resurrection,” read a statement from DreamCrew’s partner Anthony Gonzales. “Not only was this a once in a lifetime opportunity to rediscover a lost history and share the story with the world, but also gave us the ability to work with the most talented partners recreating the original vision, which still held so much untapped potential.”

But there were hurdles beyond just finding a buyer wealthy enough and interested in the project. Luna Luna was sitting in shipping containers in the small town of Nocona, Texas, and partners art attorney Daniel McClean and creative entrepreneur Justin Wills note that the Birch Foundation wanted a commitment to buy the entirety of the collection with relatively limited inspections.

“You’re driving along the road,” Wills says of his first trip to Nocona, “and from the side of the road you could see the shipping containers hiding in plain site. The ones with infrastructure in them were under an awning,” and some of the art pieces were residing in a metal barn.

McClean remembers seeing about three containers in 2018, a fraction of the entire exhibition. “It was enough to make me totally addicted,” he says.

“I recently had the opportunity to see the Ferris wheel in person and was taken aback by how fresh and new it felt, like so many of Jean-Michel’s works,” says Lisane Basquiat. “The moment was bittersweet, as I felt the joy that Jean-Michel and his friends must have experienced while working on the project.”

In relocating Luna Luna to Southern California, the park is ending up, in part, where it was always destined. After its summer 1987 run in Hamburg, where more than 240,000 people reportedly visited the attraction, Luna Luna was bound in the early ’90s for San Diego. Financial, legal and bureaucratic realities intervened, and Luna Luna has been barely heard from since.

That Luna Luna is something of a mystery, Molesworth says, is part of its appeal. “Here was this thing that existed, and disappeared, not only in reality but in lore,” Molesworth says. “It wasn’t like people were talking about it or telling stories about it. It fell off everyone’s collective radar. Then it reemerges, and it’s great.”

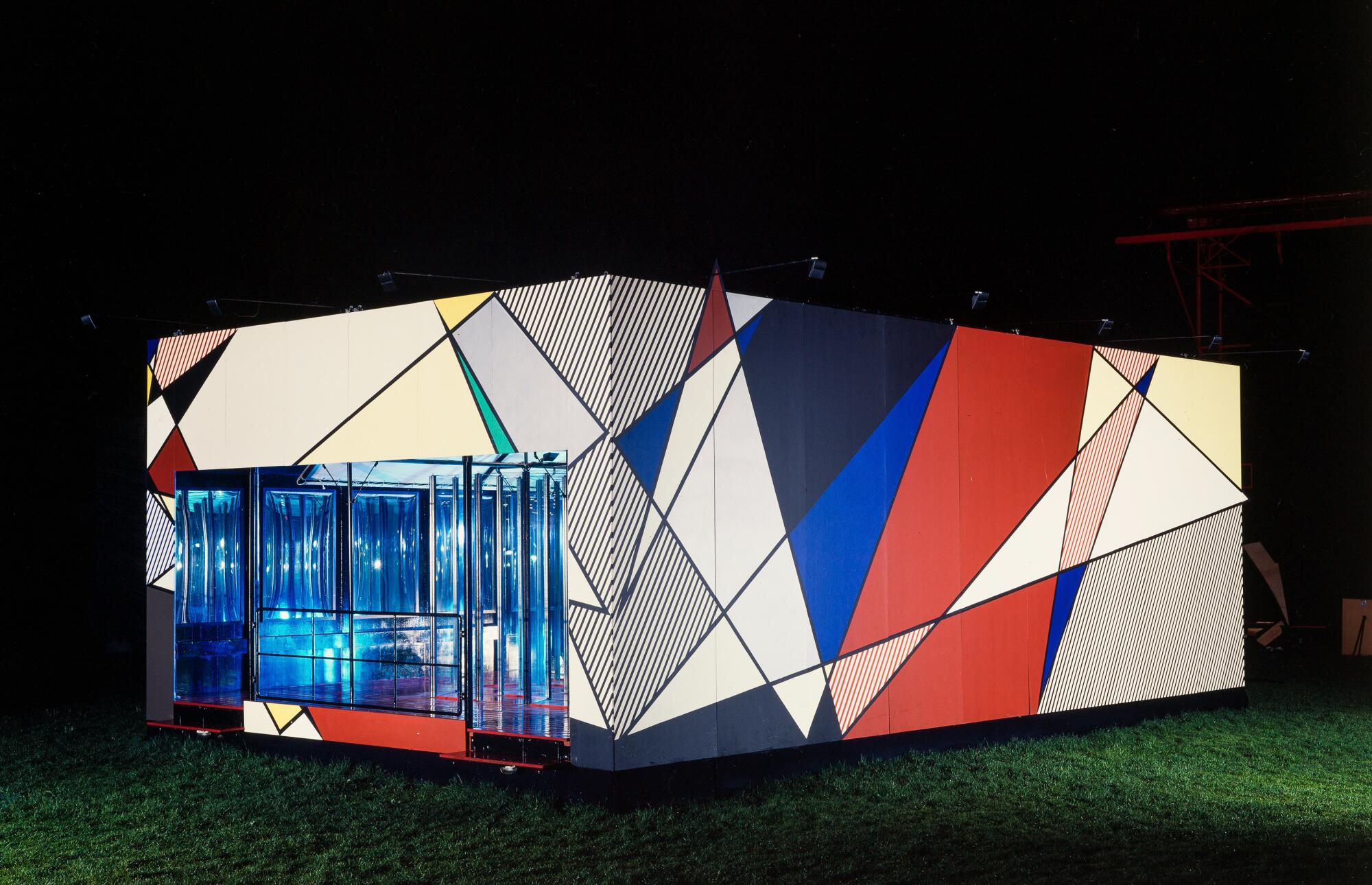

Luna Luna was in the early stages of its installation at two connected warehouses when The Times visited the space in late September. Many pieces sat in various states of disassembly and refurbishment. A glass labyrinth from Roy Lichtenstein, for instance, was largely a skeleton.

Figureheads for a Kenny Scharf swing set loomed over the reconstruction space, their elongated noses and alien-like ears setting a mischievous tone. Scharf’s swing set is striking, composed of panels of contrasting colors and objects; wondrous birds in the clouds intermix with mouths and eyes that appear as if they’re melting. McClean estimates the existing attractions were already at least 50 years old when Heller commissioned the artists to decorate them in the mid-1980s.

“I dreamt up Luna Luna with the determination that art should come in unconventional guises and be brought to those who might not ordinarily seek it out in more predictable settings,” said Heller via a statement. Heller is no longer involved in the project, stepping back after generating controversy for an alleged case of art forgery involving Basquiat’s Luna Luna work that he described as a “childish prank.”

The team has big ambitions for bringing Luna Luna to a new generation. Los Angeles is not just the first stop of a Luna Luna tour but the beginning of a larger cultural project, one that if all goes according to plan will see a new crop of today’s artists reimagining amusement park attractions. Wills couches that goal as “the grand vision,” but Molesworth is on board and the group has already been in touch with European ride manufacturers, as the hope is to someday tour something that is fully functional.

“Luna Luna: Forgotten Fantasy,” read the statement from DreamCrew’s Gonzales, “is the first installment of what will be a long-term project with a multi-faceted approach exploring the world of art and its intersection with today’s modern world.”

But one step at a time.

The goal, for now, is to teach people the history and then build the brand, to show the world not just Luna Luna but also what it means to be a Luna Luna artist. And perhaps to further tilt the cultural view surrounding amusement parks. Asked about the importance of such spaces, Wills gave a succinct thesis for Luna Luna. “This is an epicurean view of life, but the purpose is joy and fun. I think that’s why these spaces matter and why we need more of them.”

Amusement parks, adds Molesworth, “are one of the few places in our culture that cultivate intergenerational fun. You have the parent, the child, the teenager, the dating couple — there’s a place for all of those people to have a spot.”

Amusement parks, then, are not just a place to play; they’re spaces, perhaps, to better understand the world we live in.

Luna Luna: Forgotten Fantasy

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.