Newsletter

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

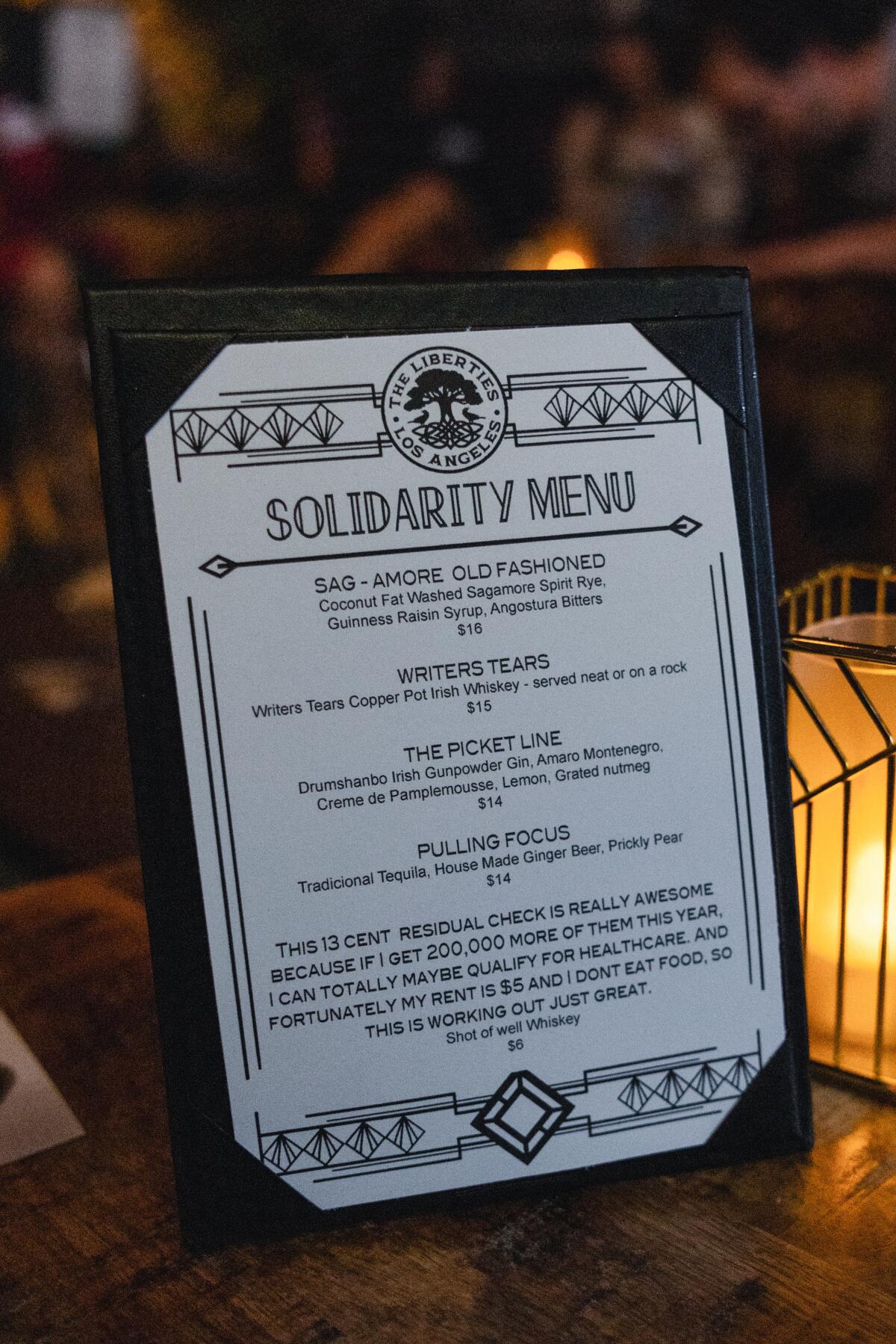

Beyond the hanging pendant lights of the Liberties, a modern Irish pub in downtown L.A., waves of laughter bellow from a private event room. Grief support specialist Rebecca Feinglos asks the nine actors and writers attending what she calls a “meet and grieve” to pick a cut-out picture of an internet meme from the table that best represents how they feel that evening.

Actor Danice Cabanela shared a meme of “Parks and Recreation” protagonist Leslie Knope, reading the caption: “Everything hurts and I’m dying.” To the others’ knowing nods and smirks, Cabanela says, “I want to hold it all together, but it’s killing me.”

When Feinglos asks those in attendance to jot down thoughts about their strike-caused grief, the room goes quiet. Their faces turn from amused to tense and contemplative for a few moments, as people fill Post-it notes before crumpling them and throwing them into the middle of the table. “Loss of potential,” one wrote. “Delaying life plans because of lack of money. Anxiety. So much.” Another wrote, “I’m grieving any sense that I’m respected or valued as an artist at all.”

SAG-AFTRA has approved a deal from the studios to end its historic strike. The actors were on strike for more than 100 days.

Strikes by both the Writers Guild of America and the SAG-AFTRA actors’ union show no signs of stopping since launching in May and July, respectively. But writers and actors aren’t just striking. They’re grieving too. Feinglos says that because union members are choosing to strike, they may hesitate to describe their experiences as grief, “and yet, that’s exactly what it is. They’re losing out. They’re feeling a loss every single day not doing the thing that they love.”

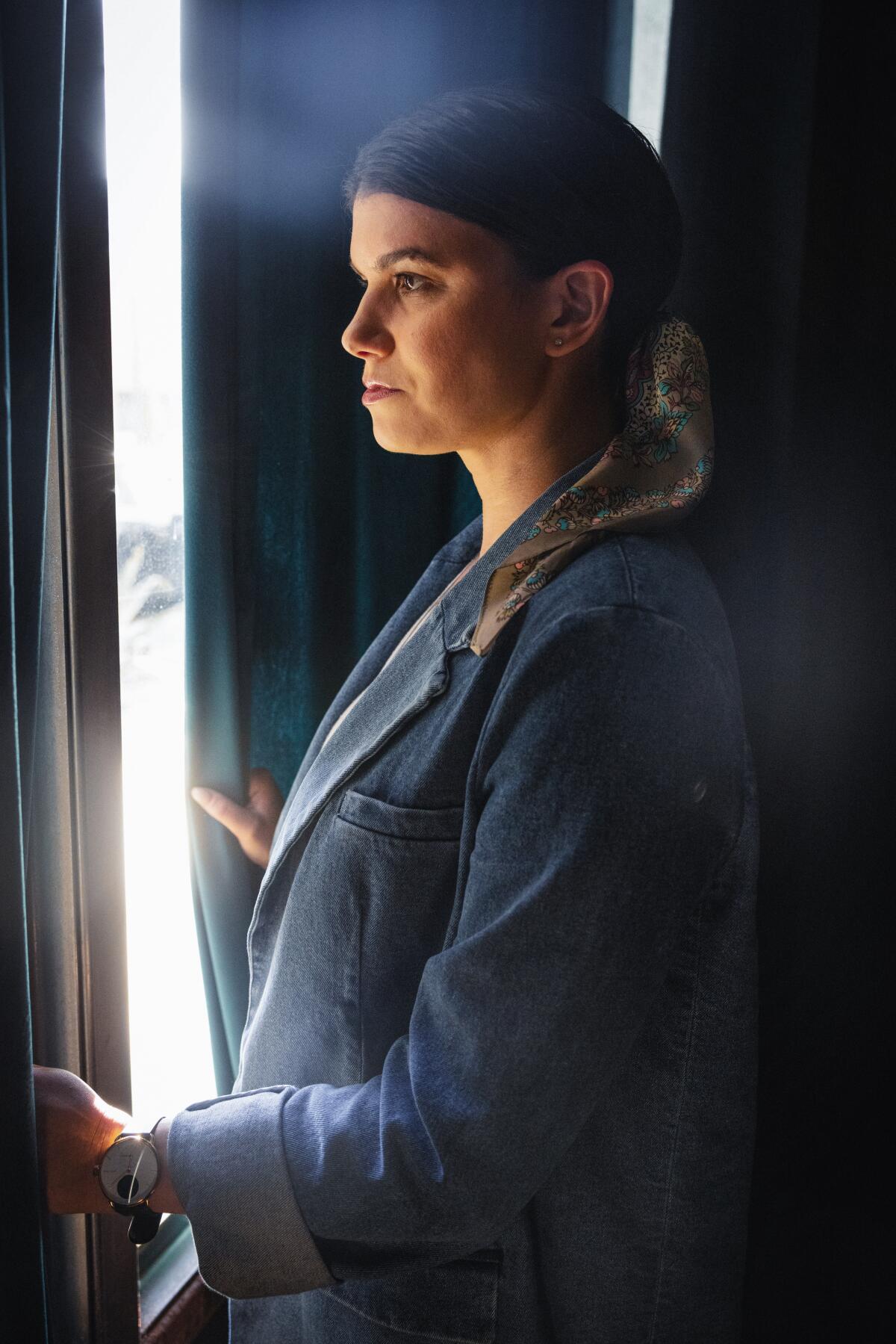

Feinglos, a former educator, founded Grieve Leave after a sequence of harrowing personal losses. The 34-year-old saw a gap in adequate grief support for people in their 20s and 30s (she was 30 at the time of her father’s death), but also to challenge the way society has made grieving so taboo. “Grief is incredibly normal” and a “deeply human thing that requires folks to be seen and valued, especially in community,” she says. Grieve Leave regularly holds virtual and in-person meet and grieves for those dealing with loss.

When a friend of Feinglos, actor and writer Jacob Tobia, whom she met when they were students at Duke University, began talking about their experience, Feinglos helped Tobia become aware of the intersection of grief and the strikes. Their grief isn’t due only to the walkouts but also predates it.

For the record:

2:12 p.m. Sept. 14, 2023A previous version of this story incorrectly stated Jacob Tobia made Rebecca Feinglos aware of the intersection of grief and the strikes. Feinglos helped Tobia make the connection.

“I refuse to be economically starved out of Los Angeles,” says Tobia, who lost a development deal based on their memoir, “Sissy : A Coming-of-Gender Story,” because of the pandemic. “Very quickly as a nonbinary person, as a gender nonconforming person, as a trans person, you learn that being” yourself is not just not enough. “It’s the obstacle.”

In 2020, Tobia moved back to North Carolina for nine months to care for their father, who suffered from neurological pain disorder and died in 2021. When they returned to L.A. last year, they lost another development deal because of HBO Max’s merger with Discovery Plus.

“With my father’s death, everyone shows up for me and knows how to support me,” they said, but with the death of their show, “it happens in the dark. It’s perceived as a failure. There’s this culture of not really talking about it.”

They described the profound anger and resentment that comes with mourning losses in their life’s work. “So when the strike began, by that time, oh, my God, was I ready [to strike].”

Finding community through picketing is one way that actors and writers are moving through these dark times. “Something like a strike is a perfect example of collective grief,” Feinglos says.

The booming beats of A Tribe Called Quest, mixed with the honking horns of passing cars outside the Warner Bros. lot in Burbank, evoke a feeling more of a block party than a picket line. But the strikers are in constant motion, holding their signs high.

Cabanela, who co-stars in Paramount’s reboot of “Frasier” but is unable to promote the show because of the labor action, says that becoming a strike captain at Warner Bros. has “renewed my sense of purpose,” likening union members there to a family.

The 2023 writers’ strike is over after the Writers Guild of America and the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers reached a deal.

Justin Halpern, executive producer of ABC’s “Abbott Elementary,” affirms that he does better when he’s connecting with other writers during this time. “I was walking with a writer right now, talking about just life and what we’re going through,” Halpern said.

“Somebody’s had a bad day or a bad weekend, and we go, ‘It’s gonna be OK. We’re with you. We’re in it together,’” says Eric Wallace, the showrunner for the CW’s “The Flash.” That exchange alone, Wallace adds, helps both people feel better, “and that has to do with the human connection,” not an artificial intelligence connection — a dig at the studios’ push to replace people with AI.

Aaron Ginsburg, executive producer for NBC’s “New Amsterdam,” who oversees the WGA picketing outside Warner Bros., says union members’ abilities to survive the labor action are due to the very nature of their industry.

“We’ve been trained by these studios to endure long periods of not working,” Ginsburg says, which has helped them build emotional strength to withstand grief and hardship. “You made us this way. You made us strong.”

The conversations at the meet and grieve downtown contrast starkly with the cheerier, hopeful talk of the picket lines.

All nine actors and writers confess their fears and disappointments and find they are not alone. Creatives are in a constant state of grief due to the very nature of their industry, having to create mechanisms to mask and cope with daily loss of potential employment, says actor Sara Fletcher.

“If you’re in this business, rejection is the name of the game,” says Fletcher. If you haven’t learned how to deal with rejection, “you will not survive.”

Actors and writers must pay Hollywood’s so-called passion tax, the notion that because they are passionate about their work, they should sacrifice a lot and settle for little to be successful.

“We keep being asked to pivot, pivot, pivot. We keep being asked to eat crow,” says actor and writer Brendan Bradley.

Actors and writers are often told that if they suck it up a little more, they will be afforded the career they want, but “the goal post keeps moving,” Bradley says.

Some acknowledge their complicity in creating the façade of what it means to be a successful actor or writer but take solace in the notion that the strikes are encouraging Hollywood to have honest conversations about pay.

Comedian and animation writer Annie Girard says social media misled her into believing that others were doing better than she was — until the strikes happened. Colleagues writing for prominent shows now admit that they don’t have retirement funds and that they can’t afford to have children. “Oh, so they’re in it too. They were just pretending they weren’t,” Girard says.

Feeling sad or hopeless ? These 12 beautiful places in Los Angeles will lift your spirits.

Rati Gupta, who found success as a recurring character on “The Big Bang Theory,” says she lost her union healthcare 18 months ago after she wasn’t able to book other SAG-AFTRA-affiliated roles.

“I was embarrassed because I was on a hit show,” she says. Hearing other friends admit that they too were at risk of losing their insurance made her feel more aware that “we’re all suffering equally, regardless of where you are in the hierarchy,” she adds.

Those at the session agreed that they wanted to maintain the sense of community that is so often absent in an industry where competition can overshadow camaraderie.

“It’s so easy to feel alone in this job, in this industry,” says Gupta. “I’m scared that when [the strikes are] over, this is all going to disappear, and we’re all going to go back to being isolated.”

Feinglos asks how they are coping. Some say they are walking in nature or finding refuge in collective action like the picket lines. For Bradley, a strike captain at the Paramount Studios lot in Hollywood who is grieving his inability to promote his first film, it’s finding and keeping a routine. “I go swimming as soon as I leave the line every day,” he says.

He sees the process of striking as like working on a film set. Every morning, he drinks his coffee and drives to the studio lot, practicing talking points for informational videos he posts to his Instagram. He’s become an unintentional strike influencer and has gained thousands of followers.

“Grief intersects with work constantly,” Feinglos says.

Some actors and writers say they won’t easily forget the strikes, that they weren’t treated fairly by their employers or that they’ve endured months of distress.

Feinglos says that what is required of strikers moving forward is to “make space for our grief by grieving every single day.” Painting, exercise, meditation and talking with their peers are ways to deal with loss and changes, she suggests.

A reader asks: ‘How do you help a spouse struggling with the recent death of a parent? When do you encourage therapy, (or) further help?’

Tobia uses empathy and compassion to process their grief, even directing those feelings toward the studios causing their pain.

“I’m in the better position here,” they said. “As weird as it sounds, being on strike is so much better than being struck.”

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.