For Dia del Niño, how Latinos can start healing their inner child

In a recent Instagram reel, poet Vianney Harelly crafts a message to herself in the form of a recordatorio de amor (reminder of love) card. It’s an exercise she learned in therapy, in which she writes down what she needed to hear as a child.

In the reel’s voiceover, Harelly says she told her therapist that she views her younger self as a secondary character in her life, “just watching and feeling and keeping it inside.”

She leaves this message on the card: “No tienes que ser perfecta. Puedes llorar y tambien puedes sonreir.” (You don’t have to be perfect. You can cry and you can also smile.)

Harelly is a writer and artist from la frontera, the border of Tijuana and San Diego. She writes poetry “to heal by revisiting old wounds and blocked memories in honor of her inner child,” her website states. She speaks to her roughly 22,500 Instagram and TikTok followers, who are largely from the Latinx community, about her experiences with generational trauma and other mental health topics.

She’s self-published five books — written in a blend of English, Spanish and Spanglish — and holds workshops across California about healing through writing.

On April 29, ahead of Día del Niño (Children’s Day, a day to honor children), she will host “Niñe interior piñata,” a “children’s healing celebration for those that are no longer children or grieving their childhood selves.”

Why are Latinos like Harelly exploring this type of healing, and how do we approach it? The Times spoke with the poet and other Latino mental health professionals for their insights.

Curanderismo is a traditional healing practice with many forms and applications. Its acceptance is growing in some corners of the medical community.

What is my “inner child”?

Not to be confused with a childlike personality, your inner child in psychological terms refers to the memories and feelings from your childhood that shape how you express yourself as an adult, said Noemí Fernández, a Long Beach-based licensed clinical social worker. Every adult has one.

Healing that aspect of ourselves means acknowledging our wounded inner child and learning to attend to our needs, providing the support our parents did not, she said.

Those needs can be acceptance, affection, connection, compassion, recreation or rest. The journey to healing may also look like processing past traumatic experiences, exploring repressed emotions and gaining a deeper understanding of yourself, she said.

Here’s an exercise Harelly learned in therapy that she often shares during her workshops:

- Close your eyes and imagine being in your favorite place.

- Your inner child is you at whatever age you choose. That child is waiting for you to sit with them.

- Imagine yourself sitting next to your inner child and think about what you would want to say. Sit with that question for a few minutes.

- Whenever you’re ready, write down anything you want to tell your inner child on a piece of paper. And try to answer the question, “What did you need to hear at that age from the people you loved?”

In this exercise, Harelly said, you explore your inner child’s past and give the reassurance and validation it needs.

Language and culture are intertwined, and many Latino Americans are seeking to learn or improve their Spanish to form deeper connections with family and their own identities.

Why are Latinos talking about this?

Many Latin American folks are reflecting on their own experiences as children, said Tina González, a Claremont-based licensed marriage and family therapist. They’re watching the kids around them and analyzing how their own childhoods affected their lives now.

A person’s inner child is wounded when they did not feel safe being themselves at home or in their community while growing up, she said. This can happen if their family struggled to pay the rent and put food on the table, if their feelings weren’t taken seriously by their parents, or if their circumstances forced them to behave more like adults than children.

These are shared experiences that can occur in immigrant communities, low-income communities or communities that deal with a lot of violence, González said. Often what happens is “children are forced to take on adult roles and responsibilities or … aren’t able to live a childhood in which their primary focus is play,” she said.

Challenging childhood experiences will influence a person’s emotional, behavioral, social and physical health later in life; for example, these experiences may have an effect on a person’s sense of safety and trust, Fernández said. They could affect a person’s ability to develop and maintain relationships. They can also make people question their abilities, self-worth and lovability.

“We might feel anxious, guarded or hyper-independent,” she said.

Harelly learned about this concept of healing her inner child a few years ago when she sought therapy at age 25.

She was experiencing a lack of motivation and immense feelings of sadness, loneliness and anger toward her parents — emotions that were brought on by hardships during the pandemic.

When she walked into her first session, she believed that her parents’ separation and the resulting disconnect with her father were the wounds that needed healing.

What she learned, however, was that her relationship with her parents had affected her inner child, a concept she had never encountered before.

She started sharing her experiences healing her inner child on social media, thinking that if this was a new concept to her, it might be a new concept to others in her community.

How to talk about mental health in a multigenerational Latino household

How do you heal your inner child?

Experts say it’s a grieving process.

In order to heal, Fernández said, you have to access part of yourself that may have been hurt, abandoned, rejected or ignored. You have to have a dialogue with your inner child and to investigate what you need.

“It’s difficult to even begin to conceive the notion that there may be a part of us that needs healing, that is unfulfilled, needs to be heard, seen and treated with compassion and kindness,” she said.

One reason it can be hard is because the wounded parts of you may have been destructive, rigid or self-sabotaging in the past. You may be inclined to criticize or bury these memories. But Fernández said it’s important to acknowledge and accept all parts of yourself and recognize the role those parts often played in protecting you in the moment.

“We can honor these parts, rather than reject them, while working on developing more compassion and fluidity in our way of being,” she said.

Harelly said she used to be very critical of herself.

“I saw how people treated me by being la hija perfecta, the good student, good citizen and la niña buena,” she said.

Harelly said she learned to think that she would get love and respect only by living up to those labels and meeting people’s and society’s expectations of her.

“Whenever I put pressure on myself or harshly criticize my mistakes, I can see my inner child being frustrated,” she said, “trying to go above and beyond her own emotional and physical health to be perfect and seen as such by her loved ones.”

But since seeking therapy and practicing writing-specific exercises, she’s learned to have more compassion for herself and others.

Healing activities aren’t limited to writing, Harelly said. She encourages people to find a creative way to explore and get in touch with their inner child.

But know that this type of healing, similar to all mental health journeys, isn’t linear or easy, Harelly said.

It can be more challenging for Latinos, Fernández said, because there’s a focus on collectivist culture, which puts the community ahead of the individual. It may be a struggle for some Latinos to prioritize themselves, set boundaries with others and admit that their inner child needs better parenting without feeling guilty about it.

“It’s hard to acknowledge that our parents or caregivers may have harmed us, for fear of being perceived as malagradecidos,” she said.

“However, by doing the very things that are difficult and uncomfortable, we can begin to break and heal generational trauma.”

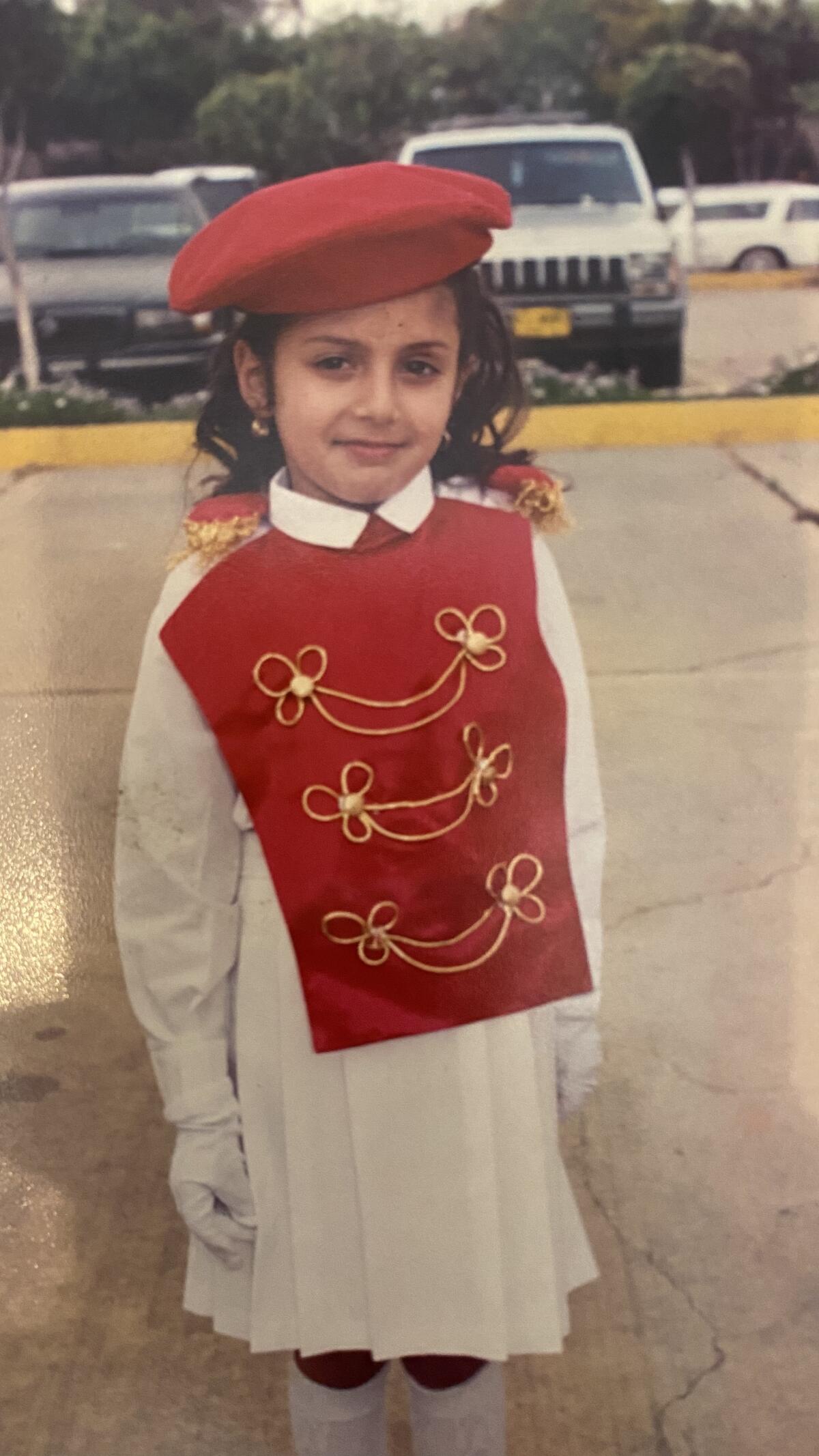

In Harelly’s home office, she has several pictures of herself as a kid on her desk.

“I have so many pictures of me as a child, because I like to be reminded that this is who I’m doing this for,” she said. “And this is who’s the most proud of me now.

About The Times Utility Journalism Team

This article is from The Times’ Utility Journalism Team. Our mission is to be essential to the lives of Southern Californians by publishing information that solves problems, answers questions and helps with decision making. We serve audiences in and around Los Angeles — including current Times subscribers and diverse communities that haven’t historically had their needs met by our coverage.

How can we be useful to you and your community? Email utility (at) latimes.com or one of our journalists: Jon Healey, Ada Tseng, Jessica Roy and Karen Garcia.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.