Accessory dwelling units, or ADUs, aren’t for everyone in need of more space. Take architect John Bertram. After many years spent living in Richard Neutra’s 900-square-foot McIntosh house in Silver Lake, Bertram and his wife, actress and writer Ann Magnuson, felt cramped and wanted more room but didn’t need the kitchen and bathroom that comes with an ADU.

So last year, over a period of five months and at a cost of $170,000, Bertram added a soundproof backyard studio that was designed and permitted as a recreation room. It now serves as a quiet getaway where the couple can work, write and meditate in the stillness of a single room.

Like many architects, Bertram has spent a fair amount of time thinking about architecture. And as someone who is intimately familiar with the work of Neutra — he has restored several homes by the renowned modernist architect including the Brown-Sidney House, which sold for $20 million in 2019 — he contemplated designing a detached addition that spoke to the architecture of the 1939 McIntosh house.

Conscious of Neutra’s famous description of his houses as “machines in the garden,” Bertram was intrigued by the concept of designing an unobtrusive addition that was a part of the couple’s backyard but didn’t overpower the landscape.

Sign up for You Do ADU

Our six-week newsletter will help you make the right decision for you and your property.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

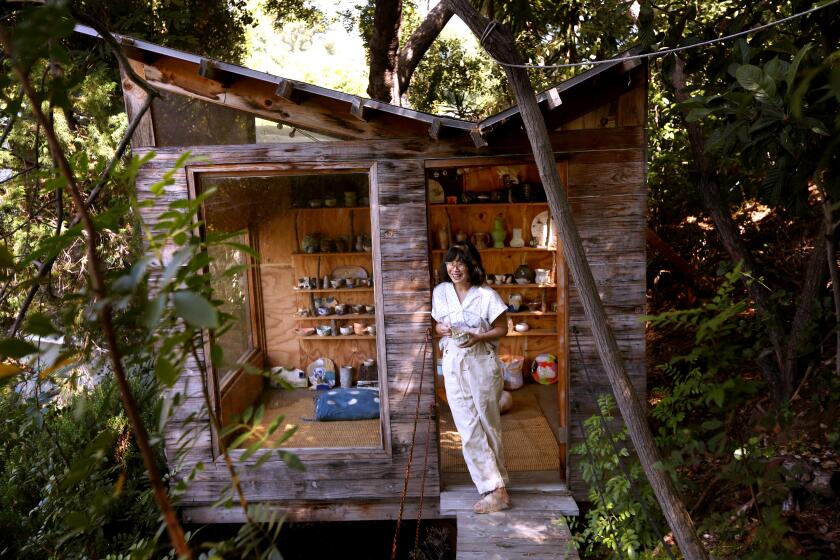

So last year, working with contractor Alon Goldenberg of Golden Touch Construction, Bertram added a simple 12-by-12- foot (or 144-square-foot) recreation room that complements the redwood-clad McIntosh House and preserves a substantial part of the flourishing yard that serves as a natural habitat.

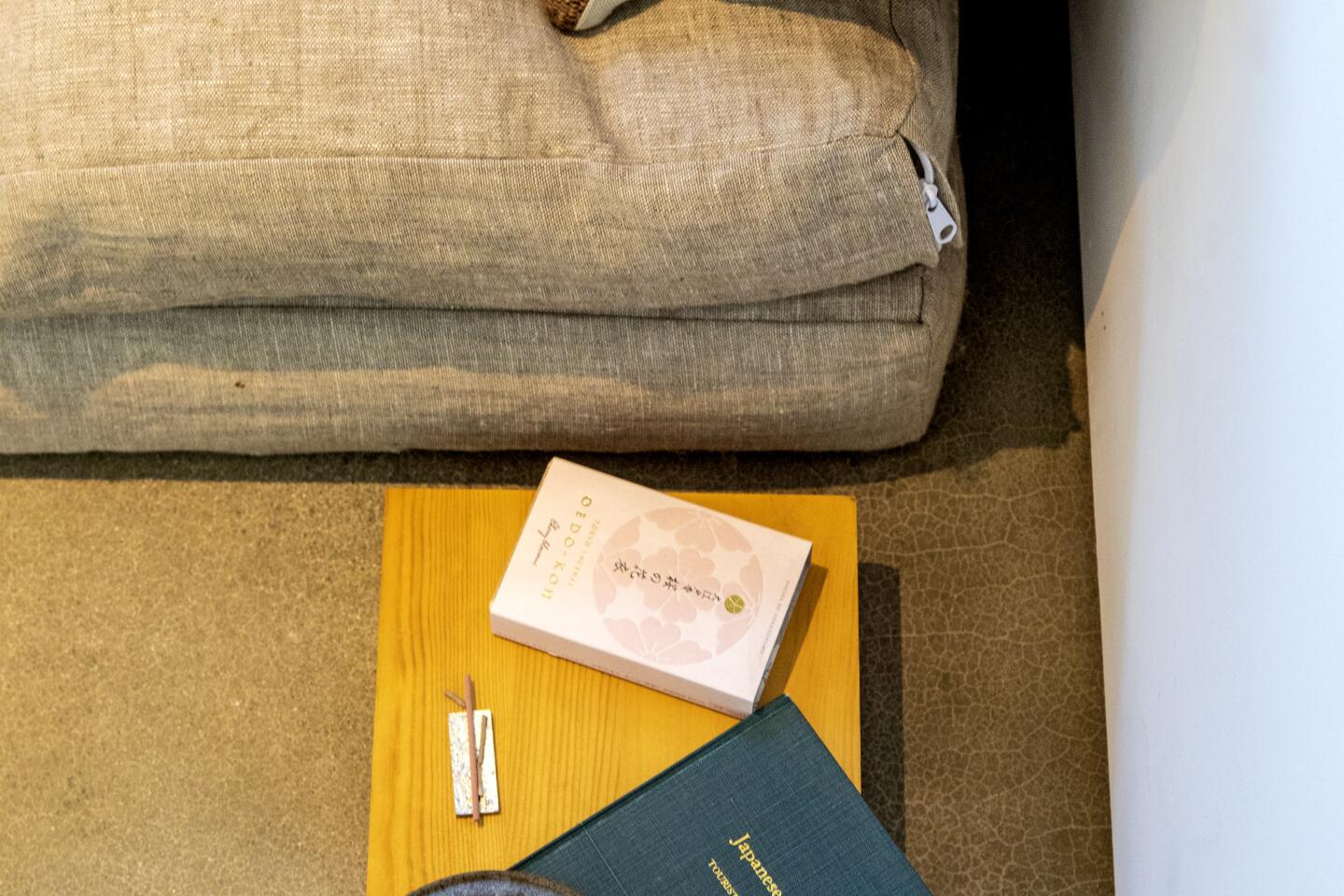

Like a Japanese tea house, the room is intentionally spare, with no visual distractions. Carefully situated on the sloped backyard behind the couple’s Silver Lake home, the recreation room has a terrarium vibe as a result of its low location and broad Fleetwood windows, including one at chest level that conveniently opens to allow Lucy, the couple’s cat, easy access to the unit. Similar to the main house, the recreation room is compact, with multiple glass windows and views that connect the house to the landscape.

“Dialogue with the existing Neutra house is very important,” Bertram says. “It needed to be seen as not competing with the house, so it is sunken into the earth by 30 inches to make it as low as possible, which not only helps with the proportions of the structure but also makes it a good neighbor.”

In a dense neighborhood like Silver Lake, where helicopters, traffic and residents create the cacophony of urban living, the architect admits the couple is more sensitive to noise than most. For that reason, it was important to design a soundproof room where they could retreat for quiet contemplation.

Bertram and Goldenberg created the acoustically isolated box by installing concrete slab flooring, isolating the structural framing from the interior using special heavy rubber clips mounted on metal channels and adding two layers of drywall on the walls and ceiling.

The Fleetwood windows and door, which Bertram says cost around $25,000, are thermally isolated, which helps to reduce the transmission of sound. Closing the door and adapting to the silence is mesmerizing, prompting Bertram to describe it as the converse of a sound bath. “It’s really a silence bath,” he says.

In keeping with the theme of simplicity, the interior is furnished with limited items: a sleeper sofa from West Elm, a desk, a chair and four oversized linen and hemp pillows that can be used as floor cushions. Four tiny dimmable LED lights add understated illumination and soft pink paint — not too blue, gray or yellow, Bertram says — adds subtle emotion to the walls and reflects the ample sunlight that floods the room.

In an unexpected touch, the structure’s roof is engineered as a deck thanks to a multilayer waterproof decking system that allows the couple to sit amid the trees and take in the panoramic views of downtown Los Angeles. “We’ve talked about putting a yurt up there,” Bertram says with a smile.

Sitting inside the recreation room, which features tongue-and-groove redwood siding to match the main house, is a captivating experience: The large windows offer views of the main house, and draw you to the garden’s original persimmon and pineapple guava trees planted by the McIntosh family in the ’30s, while the yard’s milkweed and hummingbird sage, added by landscape designer Matthew Brown, attract a constant stream of birds and butterflies.

Now, nine months after its completion, the unit has become a refuge for the couple, where they can work, record, create and relax. Eventually, they hope to use the space as a miniature project space for art and performance similar to Elizabeth Wild’s Winslow Garage, which is down the street from them in Silver Lake.

California homeowners have the right to build at least two ADUs on their property. But naturally, there are rules and costs. Here’s a guide.

Bertram says that if anyone had told him the unit would cost $170,000, he might not have gone through with the project. Still, he understands why the cost of constructing the single room was so high: the fact that it is sunk into the ground, the super-thick windows, the double layers of drywall and roof deck.

“There is a misconception that architects can figure things out inexpensively,” Bertram says ironically. “People have an idea that an ADU or recreation room should be less expensive, although it is essentially a house, with everything that goes into building one. And, perhaps paradoxically, the smaller it is, the more expensive it will be per square foot.”

When asked what Neutra would think about the ADU boom in Southern California, Bertram says he thinks he would embrace the idea with the caveat that he would have rigorous standards, even in a housing crisis.

“It’s important to note that he would set a very high bar for their realization,” Bertram says. “Neutra was not only deeply concerned with the built environment but he was also dedicated to socially and environmentally responsible design. In his book ‘Survival Through Design,’ published in 1953, he writes: ‘All our expensive long-term investments in the constructed environment will be considered legitimate only if the designs have a high, provable index of livability. Such designs must be conceived by a profession brought up in social responsibility, skilled and intent on aiding the survival of a race that is in grave danger of becoming self-destructive.‘”

It’s a philosophy that resonates with Bertram, who’s equally concerned with livability. He may work on million-dollar projects, but finds himself drawn to living in simple dwellings.

“It’s hard to make things harmonious in a house because there are so many details,” he says. “I love the idea of living with the bare minimum. There’s something exciting about living in a small space.”

Tour these tiny homes in L.A.

They were spending all their income on rent. A garage turned ADU saved them

How a struggling single mom built an ADU, without killing a 60-year-old tree

How an unremarkable alley-facing garage in West L.A. became a stylish ADU

They turned a house full of cockroaches and code violations into a ‘must have’ home — and ADU

They turned a one-car garage into a stunning ADU to house their parents. You can too

He challenged himself to build an ADU for under $100,000. What’s his secret?

She built a granny flat in Echo Park: How it saved her during the pandemic

More to Read

Sign up for You Do ADU

Our six-week newsletter will help you make the right decision for you and your property.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.