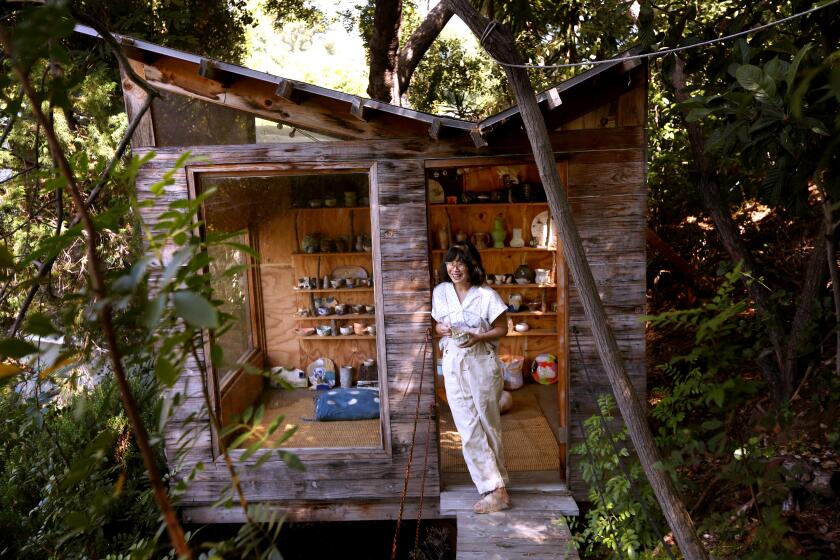

Analise McNeill is known among her circle of friends and acquaintances as the one to text about a couch on the street that looks like it might be salvageable. Her Burbank apartment is 90% furnished with found objects.

A once-cracked mint vinyl “Jetsons”-style sofa she picked up on Christmas Eve, reupholstered with emerald velvet from the 1950s. A mismatched loveseat and footstool, brought back to life in vintage deadstock fabric. A peeling, stained Midcentury Modern-looking chair next to a dumpster in Los Feliz that turned out to be an original Dux of Sweden.

She’s recovered more than 20 items since 2018, with the goal of never buying anything new again. Sometimes she’ll revamp and sell the pieces if they don’t fit in with her taste. The goal is to just get them reused.

“Literally,” McNeill, a TV writer from L.A., says, “I’ve become a trash person.”

What is Los Angeles, if not a city filled with trash people?

To the outside world, street furniture may not seem like one of the things that is, or should be, representative of L.A. It’s not the shiny sea of cars reflecting rays of sun on the 10, the hand-painted signs at mom-and-pop shops in Mid-City or the rainbow umbrellas that shade street vendors from MacArthur Park to South Central. But love it or hate it — and some people really, really hate it — these pieces are just as much a part of the cultural and visual fabric here.

“My New York friends are like, [vomiting noises] ‘Oh, god no,’” says McNeill. “But when you’re an L.A. kid, you get desensitized to other people’s stuff.”

Some Angelenos have seen so much furniture on the street in their lifetime that they’ve become blind to it — abandoned chairs and tables blending into the scenery on Western or Normandie. Others can’t unsee street furniture even if they want to.

The motivations are plenty. McNeill’s obsession with street furniture developed as a response to climate anxiety and an attempt at adopting a zero-waste lifestyle (even when she can’t pick up a piece herself, she’ll post it on Craigslist so someone might). Others become enthralled with the thrill of scoring a one-of-a-kind item for free and giving it a new home.

Then there are people like Keith Plocek, who see a discarded couch on the side of a busy L.A. street and think of it as art, worth documenting at every chance possible.

When Plocek, professor at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, purchased the domain streetcouch.com in 2010, he had a fascination with photographing the “inside stuff now being outside,” he says. He’d soon create @streetcouch Instagram and Twitter accounts, where he posts his own photos, along with submissions from around the world.

“We need to increase intercultural understanding and communication,” says designer Justina Blakeney. “Art and design can be a bridge.”

“In theory, every object has a story, but there’s something about couches,” Plocek says. “We sit on them. We sleep on them. We have sex on them. Some people die on them. To just sort of throw them out on the curb, it’s very ignominious, but in the same circuit, there’s sort of a beauty in that. You can imagine what kind of life it had.”

Over the years, he’s noticed an L.A. street couch taxonomy, which he wrote about for Vice in 2014. There’s the cushionless couch, the graffiti canvas, the keeper and, unfortunately, the toilet.

Plocek is one of a number of people in L.A. documenting or making art out of street couches. Years ago, photographer Andrew Ward made headlines for his tender portraits of couches in his ongoing project, the Sofas of L.A. An artist who goes by Lonesome Town documents “sad public installation” — sad faces painted on castaway TVs, couches, refrigerators and more — on Instagram. Sarah Pinho, a researcher who lives in Inglewood, created a Tumblr to log the rotating pieces of furniture in the alley next to her home.

Pinho is interested in this abandoned furniture as an anthropological study, especially in rapidly gentrifying Inglewood: What does this alley say about who is staying and who is being forced to leave?

“I’m very interested in furniture as a statement about how people live,” she says.

For many, though, these pieces catch attention for what they could be when given a new life, rather than what they are while they’re on the street. And that’s apparent by how quickly the good stuff gets snatched.

“It’s just amazing the speed with which stuff gets picked up sometimes,” says Plocek, who’s seen this brisk turnaround most in densely populated areas like around USC.

Zak Hailey remembers his lucky find like it was yesterday.

He was a college student living on 4th Street in Long Beach, struggling to get by and looking for free or discounted stuff wherever he could. It was late one night when he saw it as he was walking back from the beach with a friend: a floral print loveseat in perfect condition, with curvy wooden accents and cushions that looked deep enough to sink into.

“It felt like a gift,” Hailey says. “Like it was meant for us.”

Hailey and his friend walked that couch the five blocks back to his house and plopped it on the porch. He and his roommates would sleep on it. Drink beers on it. Smoke on it. Laugh on it. It became a supporting character in their lives as twentysomethings living in Long Beach.

“We spent hours and hours on that porch over the next year because of that couch,” he says.

The next special discovery came on a rainy day early last year when he scored the piece of a lifetime on a median in East L.A. It almost felt like a hallucination: “I look over, and I see the beautiful silhouette in the puddle of mud of a Herman Miller [Eames] chair.” (The same one is going for nearly $1,000 right now online.)

Small-space living doesn’t mean you have to sacrifice style or succumb to clutter.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the amount of discarded street furniture increased. According to L.A. Sanitation & Environment, the number of calls for bulky item pickup, including couches, mattresses and any other piece of furniture too big for the dumpster, went up 20% from 2019 to 2020. Elena Stern, the public information director for the L.A. Department of Public Works, theorizes that this is a result of the number of people remodeling their homes during pandemic closures or moving out in a hurry.

Hailey believes the rise in street couches over the last year could be partly attributed to a cultural shift made possible by the pandemic. Even the most experienced scavengers, he says, are more skeeved out by germs — despite what we know about how COVID-19 is transmitted — leaving everything, including the keepers, to pile up.

When it comes to the cleanliness or safety of taking a street couch home — pandemic or not — Angelenos have opinions.

Some people think it’s disgusting and unsanitary; others see it as an L.A. version of the circle of life. Some take precautions against things like bedbugs by avoiding anything made of cloth — opting for metal or wood surfaces they can wipe down. And others, if a cloth couch is in good enough shape, will invest in disinfectant spray and hope for the best.

“My dirty skin particles, how are they any better than this last person’s?” Hailey asks. “I’m just so open to seeing the piece of furniture for what it is, and what it was and what it could be — almost to a fault.”

McNeill has been able to seduce some of her most resistant friends into the lifestyle after they see the quality of stuff she’s bringing in. “I want to change the way people think about discarded furniture,” she says.

Her partner, Andrew Hobson, has never really been grossed out, more just unfamiliar with the idea of street furniture, being from a suburb outside Philadelphia — that is, until he moved to L.A. “Before there was any opportunity to be weirded out, I was more or less impressed with what we were finding on the street,” says Hobson, a comedy writer. “We were furnishing our apartment.”

Rex Dean, a musician living in Silver Lake, has always been the kind of person who slows his car when passing a pile of stuff on the street; as a kid growing up poor, this was out of necessity, he says. His first street find came when he was 4: a James Bond car toy, complete with the ejector seat. He’s collected ever since. When he had kids of his own, he passed down the tradition to them.

With shops across the city reopening for dine-in service, L.A. customers are craving more than just a jolt of caffeine.

Scavenging would shape Dean’s value system over the years — even when it became a choice. These days, Dean believes it’s immoral for perfectly good furniture to go to the trash. The count of finds in his apartment is at 15 chairs, one card table, one desk, four bulletin boards, three coffee tables, seven side tables, one bench, three lamps, six works of art, one guitar, two speakers, two mirrors, five planters and two plant stands.

A couple of weeks ago, he noticed a good-looking brown leather couch on his street that he hoped someone else would snap up. Dean already had everything he needed.

“A big driver of climate change is over-consumption,” Dean says. “And the truth is, one can feel extremely prosperous and fortunate without buying new things.”

In 2018, McNeill took a class called Waste Warriors at the Burbank Recycle Center that changed her life. It’s the reason she started picking up furniture off the street like it was her religion.

City of Burbank recycling specialist Amy Hammes runs the program. She says reuse is the most desirable option when it comes to street couches. Most furniture isn’t recyclable, she says, and according to the Environmental Protection Agency, 9 million tons of it is going into landfills each year.

Los Angeles has options for residents to dispose of furniture. People can call 311 or Sanitation Services directly for free pickup. But this way, the stories behind these pieces get lost, says Hammes, and more waste is created.

“We need to be much more restorative in valuing the things that we have and create supportive programs that make disposal not the cheapest, easiest option, but the least attractive option.”

People throw out their couches all over the world, but there’s something distinct about what happens with them here — from start to finish.

Angelenos treat street furniture hunting as an extreme sport, whether they’re looking to pick up or just snap a picture for Instagram. In one way or another, it’s about preserving stories of the city and its inhabitants.

McNeill thinks about street furniture culture as “very L.A.” for the following reasons: One, we’re a driving city, allowing us to easily drop pieces off on the curb, scope them out and pick them up if they look usable or interesting. Two, we’re in a sprawling metropolis, and street couches are a natural byproduct of that. Then there’s L.A.’s transient nature, with people always moving in or out, dropping off or picking up.

Hailey sees it more romantically — as an act of love among Angelenos looking out for one another.

“In L.A., when you find something on the street, it’s meant to be picked up,” he says. “It was put out there with the intention of somebody picking it up for free, because there’s always gonna be somewhere on the corner that can benefit from having this thing.”

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.