Grief walks with me now in the mountains. Sometimes it hangs back, letting me forget it’s even there. Other days, it rests on my shoulders, reminding me of everything I lost last year.

I’ve hiked on weekends since 2018. My husband wakes me before the sun rises. We make the hourlong trek from our Inglewood apartment to one of the many trails snaking through the Santa Monica Mountains.

There’s scarce Wi-Fi in the woods. I welcome the time untethered, even when my hips and thighs burn on steep hills. There’s something about the trails in Southern California that makes me feel seen. Nature isn’t always safe or accessible for everyone, but as a Black woman rarely am I not acknowledged by other hikers — people look me in the eye and speak.

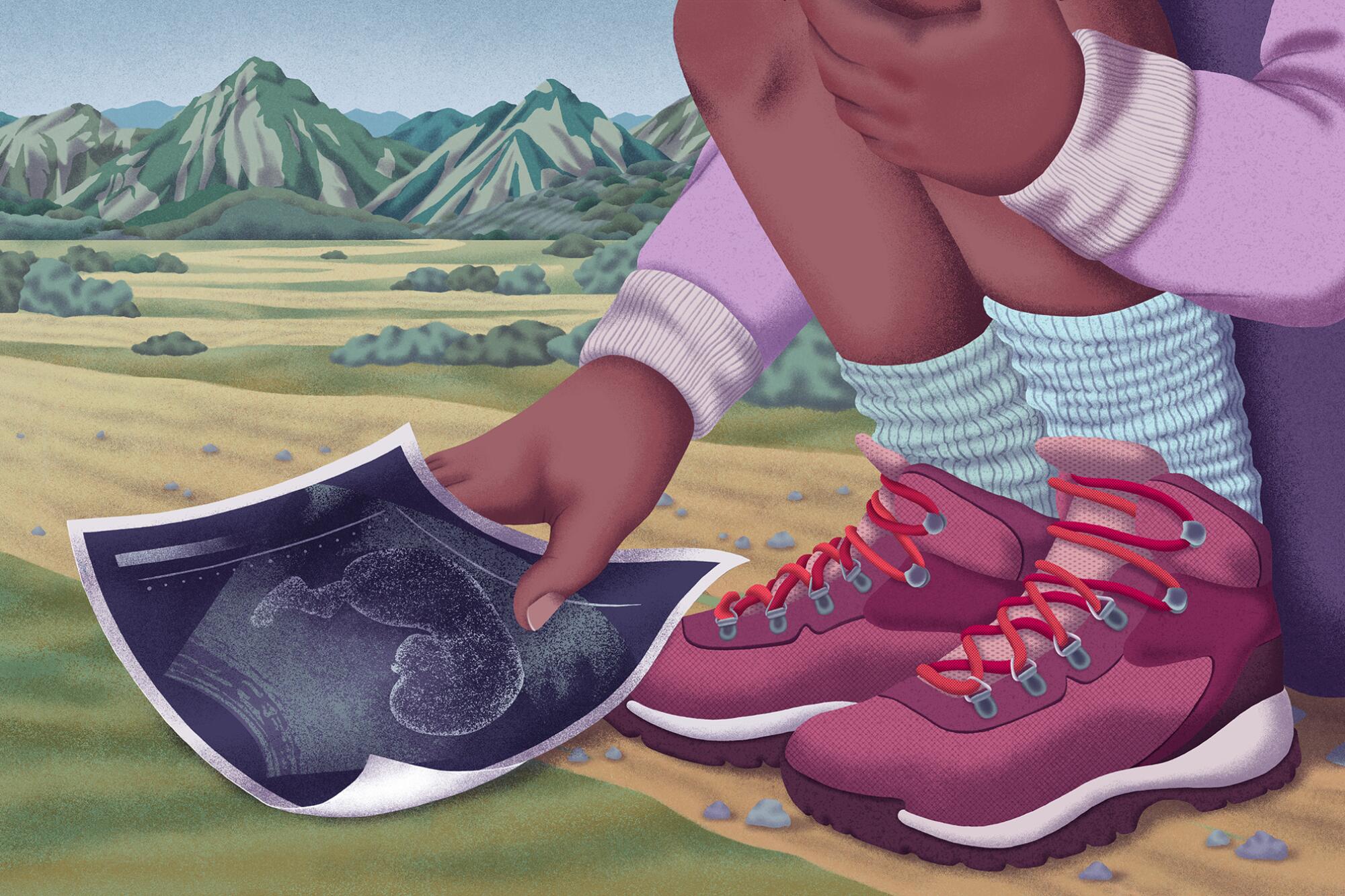

I never knew how much I craved the familiarity of my favorite hikes until last August, when my doctor pointed to an ultrasound monitor and told me my baby’s heart had stopped beating. Walking helped me remember the power of my body when I didn’t recognize it in those hazy weeks after my miscarriage.

I do not come from a hiking family.

My parents, born and raised in Compton, shuffled my brother and me off to Pop Warner football games around town on the weekends. The other days, my mother came home from her job to feed us and unwind in front of the TV. My father worked 12-hour shifts, four days a week, at an oil refinery near the Port of Long Beach. He spent most of his off days sleeping, but in summer, he’d wake up craving fresh catfish in San Luis Obispo.

Whether you’re looking for ocean views or desert landscapes or soaring mountain peaks, Los Angeles offers miles upon miles of strikingly different trails.

I went on my first hike at Camp Hi-Hill. It was 1995 — the same year O.J. Simpson was acquitted — and it was traumatizing.

Fifth-graders in the Long Beach Unified School District took weeklong trips to Camp Hi-Hill near Mt. Wilson back then. The outdoor science school was billed as many students’ “first close-up experience with nature.”

The only thing I liked about Camp Hi-Hill was the dining hall, where we were shown the proper way to eat bread. On a nature hike, I could hardly remember how to breathe when a girl later crowned “most talkative” in my fifth-grade yearbook charged toward me. She was chasing after a boy. I was in her way. Someone grabbed me before I tumbled down the ridge, but more than two decades later, I have recurring nightmares about slipping to my death in the mountains.

I’m not sure how, then, I ended up hiking at the Grand Canyon with two childhood friends on a Fourth of July weekend in 2014.

I had been working a demanding job in the music industry that paid enough for me to move out of my mother’s house but not enough to stop me from stressing about money. I was in debt from college, three years shy of 30, around the same age my parents were when we started taking those fishing trips far from the city. Their divorce in 2010 marked the start of a sad two-year stretch for me that included 22 months of unemployment, worry about my father’s health and three months working at my uncle’s smoke shop near skid row when no one else would hire me.

I needed to escape.

At the start of the hike at the Grand Canyon, I took a picture of a warning sign someone made with a black sharpie: “Beware of lightning. If you hear thunder, find shelter.”

I thought about that sign for eight hours as I hiked along the South Rim. Even on a cloudy day, the Arizona sun was too hot for my California blood; the strap of the backpack I carried left a red indent on my shoulder.

But I persisted. I felt proud when it was over until anxiety caused me to doomscroll through horror stories about fatal falls in the canyon. By the time I got home, I swore I’d never do a hike like that again.

Then I met a boy.

Godwin was born in Harare and had been living in America for 10 years when he sent me a 12-word message on a dating app in 2017. A writer too, he wooed me with stories about his youth while we ate sadza, a Zimbabwean staple that reminded me of thick grits.

The extra pounds that sometimes accompany new love is what prompted his invitation to join him for Saturday hikes eight months into our relationship. We went on our first hike together — a short, two-mile trudge from Trails Cafe in Griffith Park up to the observatory — in the spring. I spent most of the walk with my hands pressed against my hips, winded.

The next day, I told my girls about his plans to take our relationship 1,000 feet above sea level at a small gathering for my birthday. “He wants to start hiking every Saturday,” I slurred. We were drinking margaritas at an overpriced Mexican restaurant in Santa Monica, and I was shouting. I swore the first hike would be our last, but the next week Godwin was shaking me awake before the sun was up. Twenty minutes later, he was driving us to the Santa Monica Mountains, a place I saw burning almost every year on the news since I was a kid.

The Los Liones Trail is lined with chaparral and peaks around 1,200 feet. On a clear day, you can see Catalina Island and multimillion homes in the Pacific Palisades, a city I had never stepped foot in despite growing up 36 miles away.

At a clearing on the trail, there’s a wooden bench dedicated to Roberta Hollander Rapier. The plaque says she “walked the path of life with generosity and courage.” Sitting on Roberta’s bench, I decided I wanted to be the same kind of woman.

Why hike in Los Angeles? Lots of reasons. Use our guide to navigate 50 trails in Southern California, plus tips on gear and treats for the trail.

I’ve missed few Saturday hikes since.

Soon I was the one convincing Godwin to dip his toes in ice-cold streams in Altadena and then out for gyros at Torino’s afterward. On another hike, we got caught in a magical swarm of yellow butterflies.

Then one weekend in October 2018, we drove down to Torrey Pines in San Diego. I love hiking in the reserve there because I can walk to the car barefoot after descending 300 feet to the sandy beach. I was wondering out loud if dolphins near the U.S.-Mexico border were bilingual when Godwin asked me to marry him.

We exchanged vows outside on a hot day the next year in September. It was the last time our families were able to come together before California shut down because of the pandemic.

Six months later, we were stuck in our small, one-bedroom apartment in Inglewood, which was now doubling as our office. The threat of the virus — and the fact that both of my parents are essential workers — took my anxiety to an all-time high. One night in April, I rushed to the ER with chest pains, convinced I had COVID-19. It was my first anxiety attack.

Walking helps quell the doomsday scenarios that scroll like a flickering marquee in my brain. When the virus closed our favorite trails, my husband and I began to explore our own neighborhood. I snagged a Tayari Jones book from a pink Little Free Library around the block, and we discovered an open trail in Baldwin Hills.

Traffic snarls near the Stocker Corridor Trail on La Brea. It’s a breezy hike. But one morning in late June last year, I found myself on Stocker unusually winded.

A few days later, I peed on a stick and found out I was pregnant.

The coronavirus has reshaped healthcare and the way in which people give birth. When I made my first prenatal appointment, a nurse politely told me Godwin couldn’t even sit in the lobby. He was forced to join us by FaceTime — far from ideal. Three minutes into the video call, Godwin’s face lit up from hearing a strong heartbeat.

My doctor signed off on our hikes. So we continued to go on Saturday mornings. We pitched each other stories. We noticed bougie all-terrain strollers we hoped to include on our registry.

Godwin thought we were having a boy. The name we picked rolled off his tongue like he had known the child for years.

On Aug. 14, at my 12-week appointment, I FaceTimed him again from an examination room. I had read that sometimes it’s hard to see the baby at this stage with an abdominal ultrasound, so I didn’t panic when my doctor asked me to put both feet in the stirrups. She slid the transvaginal wand inside, and even though her face was covered with two masks, I knew something had gone wrong.

The baby’s heart wasn’t beating.

The medical term for what happened to me is called a spontaneous abortion, but we tell everyone I had a missed miscarriage. It lands softer.

My body showed no signs of the loss until three days after that terrible doctor visit when my brain finally told the rest of my body to pass the baby. When I got tired of sweating through my clothes on our bathroom floor, I asked Godwin to take me to the emergency room at Providence St. John’s.

Because of the pandemic, he wasn’t allowed to come inside with me. Godwin and my mother remained in the makeshift waiting room outside. Only one person — a kind, gray-haired doctor — at the hospital asked me how I felt about “losing my baby.” He told my family I was having labor-level contractions, but I was going to be OK. The next morning, after D&C surgery, Godwin took me home. I was no longer carrying our baby.

I spent the next 14 days binge-watching TV and answering work emails in a haze. I did this until I thought our apartment was going to swallow me. My church in Compton was closed and the virus made me afraid to visit my family. But there was only one place I really wanted to be: my favorite spot at Malibu Creek State Park, just above Century Lake. The rocks in the mountains look like faces.

We visited the park on Aug. 29, and I thought about how the last time we were there, I had no idea my baby’s heart hadn’t pumped for nearly three weeks.

Longtime oppression and historical barriers have kept many people of color from feeling comfortable in the American outdoors.

Godwin was doing everything right and our walks improved my mood, but I needed more help. Shortly after our first wedding anniversary, I told him during a hike in Calabasas that I needed therapy.

My therapist taught me that all of my feelings about my loss, even the complicated ones, are normal, which was a relief. On quiet and empty trails, I think about the baby. I don’t see a raspberry-sized human on the ultrasound screen. I see my child in a Man-Utd jersey matching their daddy‘s. The hardest part about my miscarriage is the sudden disappearance of the dreams I had for our family.

March 6 was our due date. As it approached, I lurked in subreddits about pregnancy loss. I expected the day to be hard. Some people recommend hosting an intimate memorial. I read an article about Jizo statues planted in Japanese cemeteries in memory of the unborn. I started to think of a way to memorialize my baby.

I decided moving my body was the best way to spend the day. Godwin and I settled on a four-mile trail in Malibu Creek State Park. When we started the hike, near Mulholland Highway, we could see the hill that usually gave us trouble, hundreds of feet below. It looked flat from where we stood.

We spent the next two hours struggling up and down the slopes until we reached a clearing overlooking Malibu Lake. We sat on rocks and tried to catch our breath. Godwin called his sisters in Harare; we laughed with them on WhatsApp about the hot weather. I was exhausted, but I felt good.

Around one in four pregnancies end in miscarriage, yet we still don’t know how to talk about it. During these last seven months, friends have reached out to tell me about their own losses. Reading other women’s stories helps me too.

I wanted nothing more than to be fussing with a complicated baby carrier on hikes this summer, but the brevity of my child’s life has inspired me to shake up my own. I left my job in February to write full-time. I am free now to spend more time outdoors.

That does not stop grief from making an appearance. I don’t know if or when it will ever go away. When it does show up, I lace up my sneakers, wiggle into a pair of tights and hit a mountain trail. My favorite thing about a summit view is looking down at how far I’ve come.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.