The Black history you didn’t learn in school is being taught on TikTok

Put away your textbooks and pull out your cellphones: some of the best Black history lessons are happening on TikTok.

Across the app, Black creators are posting videos that confront America’s racist past in graphic detail, use history to add context to the way race is viewed today and view history through a lens that addresses the way homophobia, colorism, age and respectability politics influence who history remembers best. They go beyond the surface level explorations of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks that run rampant during Black History Month to examine lesser-known figures, and they don’t limit themselves to February.

They’re also fun, youthful and modern — PBS, this is not. (No shade.) The creators bring some of the best elements of the app — the humor of Gen Z and young millennials, green-screen backgrounds, low-budget props and popular music — to content that’s both educational and entertaining in a way history lessons so rarely are.

In her viral TikTok video on “that one time 5,000 Black kids went to jail in Birmingham,” Lynae Bogues, a 26-year-old influencer and poet based in Atlanta, plays both the sheltered student and the teacher frustrated by what isn’t commonly taught in schools.

“Five thousand Black kids?” she asks.

Bogues goes on to explain the history of the Birmingham Children’s Crusade, when thousands of young Black children protested and marched in the Alabama city — facing police dogs and firehoses — in May 1963. In the comments, some viewers shared that they were familiar with the protest — their parents were there, they said. For others, seeing the video was a mixture of shock (that they didn’t know) and disappointment (because they should have). That mixture of emotion helped spread the clip across the app — the video has been viewed more than 2.8 million times and helped Bogues gain nearly 100,000 followers this month.

“Even talking to my parents, my mother from Mississippi, she had no idea that something like that had happened,” Bogues said.

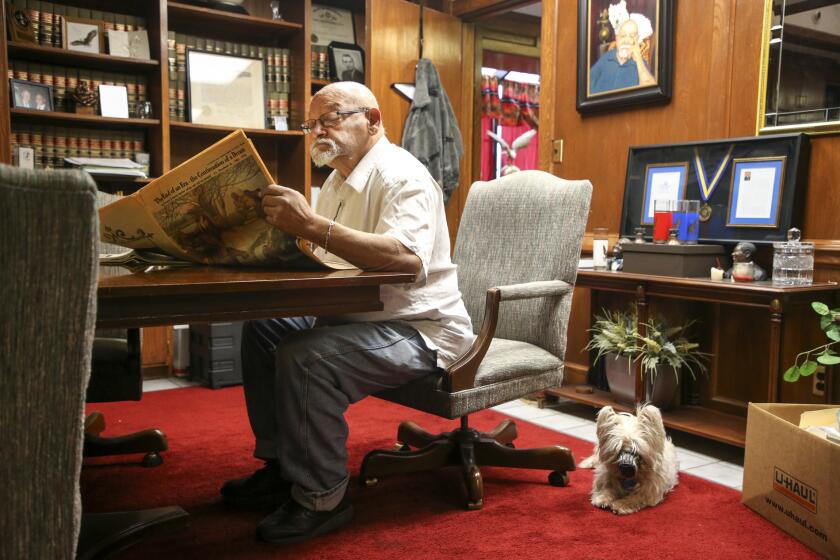

The internet is often rife with misinformation, especially on issues related to race, but any platform that “helps us tell these stories” well and accurately is good, said David Pilgrim, a sociology professor at Ferris State University in Michigan and founder of the school’s Jim Crow Museum. The museum displays and provides context for racist memorabilia in an effort to paint a full picture of American history.

“I am often somewhere between disappointed and dismayed at the lack of knowledge of our country’s past that we find not just in young people, but even older people,” Pilgrim said. “I use to joke that if you don’t make a movie about it, people don’t know it happened.” On TikTok, people are making do with just a minute.

February is Black History Month, and pandemic or no pandemic, there are still plenty of ways to celebrate virtually.

In the last year, TikTok has outgrown its reputation as a platform that solely features videos of young people dancing to popular songs to include educational and instructive content. In the wake of last year’s racial justice protests, the app has also sought to highlight diversity within its community. To mark Black History Month the app has held a series of livestreams and musical events. TikTok also named 100 people to itsBlack creatives incubator program to help them build their brands.

At the same time, Black creators have noted that clips addressing racism are sometimes flagged as hate speech by the app, while elsewhere actual hate speech is not always taken down promptly. (“Racism, hate speech, harassment absolutely have no place on TikTok,” said Kudzi Chikumbu, TikTok’s director of Creator Community.) In some cases, they’ve been accused of being divisive; other times they’ve had to create workarounds, such as spelling certain words — like “negro” — with numbers and symbols to avoid being flagged. “I have my days with TikTok, to be honest, it’s a love/hate thing,” said Nick Courmon, a 23-year-old who shares Black history through spoken word poetry on the app.

Despite TikTok’s problems, there is a clear audience for the kind of educational content Black creators are bringing to the platform. Here are four Black creatives who’ve gone viral sharing the history that’s often forgotten.

Lynae Bogues, @_lyneezy

Bogues started off on Instagram, where she has a following of more than 144,000. There, she hosts a segment, “Parking Lot Pimpin’,” that covers topics like misogynoir (discrimination against Black women) and colorism. She moved to TikTok to reach a new audience.

As a child, Bogues said she actively sought out opportunities to learn more about Black history. In her language arts and science classes, she noticed that the figures she was learning about were predominantly white. “I just knew that there was such a wealth of Black people creating and making history,” she said. Her experience as an undergraduate at Spellman College, a historically Black institution in Atlanta, was a complete 180: Suddenly, every class was taught through the lens of Black studies, she said.

Bogues got a master’s in African American studies at Boston University, then taught history and ethnic studies in Georgia. There, students who’d taken ethnic studies under a previous teacher would say: “Oh, man, last year, when I took this class, all we did was watch movies, all we did was write about Frederick Douglass,” she said. “What I brought to the class was talking about little-known figures, little-known moments, that have larger implications to their everyday lives.”

She’s taken that same approach to her videos. In one TikTok, described as “Things you thought Martin Luther King Jr. did but he didn’t,” she explains that the Montgomery Bus Boycott was actually started by Jo Ann Robinson, a member of the local Women’s Political Council. In another she argues why “the concept of race has no scientific bearing” and how it relates to eugenics and scientific racism.

Kahlil Greene, @kahlilgreene

Kahlil Greene, a senior at Yale College studying the history of social change and social movements, started his TikTok account in January with videos calling out the “whitewashing” of King’s legacy and highlighting his quotes on race and class. But he’s best known for his “Hidden History” series that explores “crazy, creepy and/or covered-up American history.”

On Presidents Day, he asked, “Did George Washington take his slaves’ teeth to put in his own mouth?” In another he asks, “Did white people organize real-life Hunger Games for Black kids?” In the third video in the series, he looked at evidence suggesting Black babies were used as alligator bait by white hunters in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Greene said the inspiration for each video often comes from things he heard mentioned by relatives growing up. “These were told to me through oral histories, because my family is Black in America,” he said. “These were things that were passed down, and they really shaped my perception of American history.”

While family stories sparked some videos, Greene does his research and shows his work.

“The sources are always listed in my videos,” Greene said. “That’s something I always make sure to do, so in the case that someone does disagree with me, and they have a valid argument, they see where I’m pulling the sources from, where I’m pulling the quotes from.”

A black-owned Oklahoma newspaper would not let the state forget the day white mobs murdered hundreds of African Americans in Tulsa.

Nick Courmon, @ndcpoetry

At first, Nick Courmon, a graduate student in African American studies at North Carolina Central University, didn’t want to join TikTok.

“I was very, very hesitant on using TikTok, primarily because I had my own preconceived notion of it,” Courmon said. “I was thinking that it was just this app that was just kids dancing and doing all kinds of nonsense.”

When he did come around — after being convinced by friends and a podcast interview he heard featuring a famous TikTok poet — he quickly began posting spoken word poems dedicated to historic moments and figures like Fred Hampton of the Black Panther Party, the history of dap, the activism of Afeni Shakur (Tupac’s mother) and Rosa Parks’ work with the NAACP as an advocate for Black women who’d survived sexual assault.

The role of Black women in the civil rights movement is a common theme in his videos. “We need to understand that although Coretta Scott had Martin’s back, she was the woman beside the man,” Courmon says in a video highlighting her political work.

Courmon’s parents both attended historically Black colleges, and as a kid he made his way through their collection of African American history books and gave reports on what he learned. In school, he would interject during history lessons in an attempt to add context to what was being taught in class.

Through his TikTok he’s been able to engage his more than 85,000 followers, as well as expose them to spoken word poetry. Courmon said he’s noticed that people will sometimes watch several videos before they realize “‘Oh, wow, you’re doing poetry? Oh, wow, you’re rhyming. Oh, my God, that’s crazy,’” he said.

Sometimes, though, the rhymes are clear right from the start. His video on Josephine Baker‘s work as a French spy during World War II opens with this: “Before there was Beyoncé, there was Josephine Baker, a beautiful Black woman who sang, performed and popularized shaking her money maker.”

Taylor Cassidy, @taylorcassidy

In 2020, Taylor Cassidy started her “Fast Black History” series, which features short videos on figures like researcher Percy Julian; Zelda Wynn Valdes, the designer behind the original Playboy bunny costume; and Jane Bolin, the first Black woman to graduate from Yale Law School and serve as a U.S. judge.

Cassidy, an 18-year-old creator who just signed with WME, said her “Fast Black History” series helped cement her presence on the app, where she has 2.1 million followers. In 2020, TikTok honored her as one of the year’s “Voices of Change: Most impactful creators.”

One of her favorite videos, published last May, tells the story of Mum Bett, also known as Elizabeth Freeman, the first female African American enslaved person to successfully sue for her freedom in Massachusetts. As Cassidy says in the video: “Mum Bett was a bad chick, period.”

“Initially, I was just having all of these thoughts: Oh, nobody will like it, people are getting bored of this, you shouldn’t do it,” she said. The video is one of her most popular, to which she credits her props, music choices and costumes (she dresses as both Freeman and her lawyer, who argues the court needs to add some “seasoning” to their reading of the phrase “all men are created equal” in her reenactment).

Cassidy’s interest in Black history started at home. Before she was born, her mother bought 10 books on Black historical figures with the intention of sharing them with her future children, she said. As a kid, Cassidy’s mother would quiz her on different figures during car rides.

“At home, I would hear about all of these different Black history figures and events, whereas whenever I would go into school, it would be the same three Black people every time, every year, every month,” Cassidy said. “The Black history that I fell in love with so much didn’t come from my school education.”

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.