They build gardens for the rich and famous. And they still get stopped by the police

“You’re so far beyond all that race stuff.”

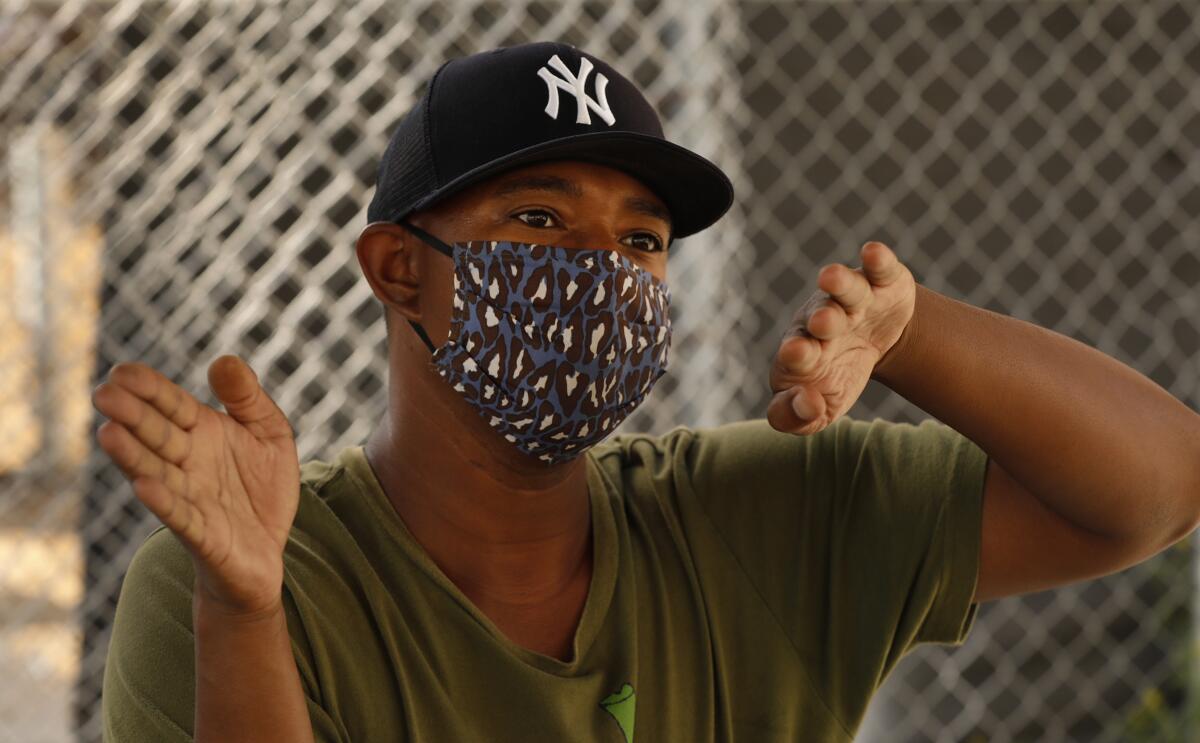

The comment stopped Logan Williams cold. The Beverly Hills High School grad was selling vegetable plants to a regular customer at his Silver Lake nursery, Logan’s Gardens, the business his father, Jimmy Williams, started some 19 years earlier.

It was June 2, and elsewhere in Los Angeles, large groups were peacefully protesting the police actions that led to the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis eight days earlier. Others had resorted to vandalism and looting in Hollywood, Fairfax, Santa Monica and downtown Los Angeles.

Logan and his father are African American and, as far as they know, the only black nursery owners in Southern California, but they didn’t join the protests. Like most nursery owners, they’ve been way too busy. Their business has more than doubled this spring as demand for vegetable plants has soared. Moreover, Logan and Jimmy also build and maintain custom gardens for the rich and famous around Los Angeles, and their phone hasn’t stopped ringing since mid-March, when people stuck at home due to coronavirus concerns became eager to start gardening.

As coronavirus restrictions lift, firms are getting back to business and hoping for your support. Here’s a list.

So the protests and George Floyd were all jumbled with a lot of other things in Logan’s mind that day as he and his white customer finished their transaction and chatted about current events.

And that’s when the customer said, “You know, Logan, you’re so far beyond all that race stuff.”

Logan said he didn’t sleep well that night, and the next morning, when he woke at 4:45 a.m. to prepare plants for their bi-weekly sales at the Santa Monica Farmers Market, he took a moment to post a personal story on Instagram, something he said he rarely does.

On the Instagram post, you can see Logan grimace as he recalls this story. “I guess to him, I was just some well-to-do black dude who was beyond all this stuff going on in the world,” he says on the post, “but as a black person, and particularly a black person in America, I know you can never be beyond that race stuff.”

I asked the father and son to discuss their thoughts on this moment in Los Angeles and to share some of their experiences as African American men living and working across the city. In a phone interview that took place shortly after his social media posting, Logan sharedthat he enjoyed a rarefied upbringing. He said he went to schools in Beverly Hills because his mother was the top sales person and interior designer at the Polo Ralph Lauren store on Rodeo Drive. He didn’t know until he was an adult that it was unusual to have best friends who were the children of the Argentinian consul or Persian Muslims, or half-Brazilian and half-Japanese.

He recalls a wait-a-minute moment with one of his close white friends at the Beverly Center, when they were around 20. They went into a shoe store to buy something, he said, and when he pulled out his credit card to make a $20 purchase, the sales clerk asked to see his ID.

Many of us grieving about the state of the world — illness, injustice, inequities — are turning to our victory gardens, or the potted tomatoes and basil on our balconies or patios, for the tiny moments of respite they provide.

Logan thought that was normal, that everybody had to show their ID to make a credit card purchase, but his friend was surprised. “He said, ‘Logan, do they check your ID every time you pay with a card?’ because he’d never been checked when he paid with a card .... That’s when he realized how race affects things.”

That comment, about being “beyond all that race stuff,” has dredged up too many memories, he said, of events that affected him and his father — “where I was literally minding my own business and things still went totally wrong for me.”

Like the spring of 2018 when he went to a longtime customer’s home in the Hollywood Hills to plant her spring garden. He finished around 1 p.m. and then climbed inside his work van to write an invoice.

“I was just sitting there, looking down at a sheet of paper with a calculator in my hand when all of a sudden I hear someone slapping the hood of the car,” he said.

“I see this guy glaring at me ... but before I can react he literally shouts at me, ‘Who are you? What are you doing? I have security concerns!’”

Logan said he didn’t know what to say or do. “I’d literally just been planting flowers and herbs at the home of a very nice, older lady. The only thing I could think of to say was, ‘I’m working’ in a perturbed voice, and [the man] just walked away.

“But as I was sitting there, shaken, it hit me then. I had this silver calculator in my hand. What if I’d raised my hand and what if he had a gun and shot me because he thought I was going to shoot him? And that’s something that sticks with you.”

Logan is 34, a sometime stand-up comic who once thought he’d become a sports broadcaster. But talking about the Hollywood Hills event makes him remember so much more.

The main concern of black people right now isn’t whether they’re standing three or six feet apart, but whether their sons, husbands, brothers and fathers will be murdered by cops.

Like the time in 2015 when he and his then 74-year-old father treated themselves to a workday lunch at El Caserio in Silver Lake, one of their favorite restaurants. “It was a nice father-son lunch, and we left in the van together,” but a few moments after they left the parking lot, he said, they were pulled over by an unmarked police car.

Two officers stood on either side of the van, one at his dad’s door and one at his, and when his father rolled down the window, “The officer doesn’t even ask a question,” Logan said. “He just makes one of those open-ended statements: ‘We’ve been having trouble with robberies in the area,’ and left that hanging out there, as if we had any information for him; two black guys in a truck, so we’re robbers now or something? I mean, what response can you make to that?”

His father told them, “‘Look, I’m a gardener,’ and he told them what we did, and the officer said, ‘Oh,’ and that was the end of it.” They checked his ID, which took about 10 minutes, and then we were let go.

Breonna Taylor, 26, Tony McDade, 38, and many others didn’t live to see their 40th birthdays. They were killed by police.

Then there was the time in the mid-1990s when his dad used to jog in their Larchmont Village neighborhood. He often saw a neighbor gardening, and they would occasionally talk about plants, so one day, Jimmy put a plant in a brown paper bag to take it over to this neighbor’s house as a surprise.

“He’s literally a guy bringing a tomato to somebody the next street over when two LAPD officers pull over and ask him, ‘What’s in the bag?’” Logan said. “He’s walking a block away from his house, and he’s able to talk his way out of it; one of the officers was even a Latina woman who gave him her card and said, ‘If you have any complaints, this is the number to call.’ But this easily could have gone a whole different direction.”

They’re all unrelated incidents, he says, except they’re not: “He was literally just walking with a plant. ... In all three instances we were doing something around plants, and even that was not enough to protect us. It’s just part of being black in America; at some point you’re going to feel it. You can either block it out, keep working, and move forward or sit there and be upset. You don’t have an option, and you feel bad either direction you go. It’s just an added burden.”

Jimmy is 79 now. He wants to talk about how well his business is doing, the son he’s so proud of and his new recipe for pickled zucchini (you have to use apple cider vinegar, not white vinegar). He said his great-grandmother was a slave in South Carolina, a descendant of people renowned for farming even before they were brought to America. Everything he knows about gardening, he said, was passed down through his family.

He’s sympathetic with the protestors today, but he doesn’t think they’ll change much. “When these things happen that involve racism, the rich white people are not affected by it,” he said. “They just turn their backs and wait until it goes away. Those white people have to get involved in the change; they’re the ones who have to make the change.”

Fashion brands supported #BlackoutTuesday on Instagram, but is that really enough? TV host and style expert Melissa Chataigne has some thoughts.

Logan sees it a little differently. “My dad’s seen every protest march since the civil rights movement started, and it’s gotten to the point where he’s seen people marching a jillion times. You can ask for this or that until you’re blue in the face, but that’s doesn’t mean anything is going to change.”

Logan thinks the answer may partly be in education. “We really need to reform the way black history is taught in conjunction with American history,” he said. “Maybe if we explained the contributions a little better, the different races would have more respect for each other. I remember my mom and dad bought me books about black history because they knew it was not being taught to me in school.”

But mostly, Logan said, he thinks the changes will come from individuals making decisions every day. One of his white friends messaged him after George Floyd was killed to see how he was doing.

“She said, ‘What can I really do to help, other than say, “I’m sorry” or “Black Lives Matter”?’ And I told her, ‘Just keep doing what you’re already doing. Part of what helps is when you genuinely value black people for who they are and what they do. Spend a couple bucks at black businesses and tell your friends about them. Really, just treat us the way everybody wants to be treated. That’s where it starts and it helps so so much ... you’ll never be able to really know.’”

Watch LA Times Today at 7 PM/10PM on channel 1 on Spectrum News 1, and on Cox systems in Palos Verdes and Orange County on channel 99.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.