This story is part of Image’s April issue, “Reverie” — an invitation to lean into the spaces of dreams and fantasy. Enjoy the journey.

Two weeks after I lost my sister, she visited me in a dream. Was it her, or was the dream a construction of my psyche, made to process this sudden loss? Either way, it shook me to my core.

Since childhood, I’ve transcribed thousands of pages of dreams into bedside notebooks in the dark, but it wasn’t until I studied dream work, using techniques pioneered by Carl Jung and adapted for artists, that dreams began to change me.

Dream work can be described as the process of interacting with unconscious material to generate deep, truth-charged work. Guided into a state of embodied meditation, the dreamer can “talk” with any element of the dream — characters, objects, room, weather. Shockingly, it all talks back.

I first learned of dream work when I joined a theater company alongside Kim Gillingham, who founded the organization Creative Dream Work in 1999. Over the years, Gillingham has revolutionized Hollywood’s approach to artmaking through her work with Sandra Oh, Benedict Cumberbatch, Jane Campion and other luminaries who draw on their dreams to create unflinchingly authentic characters on screen.

“We’ve all developed personas, taken certain aspects of ourselves and hidden them away in order to walk through the world,” Gillingham told the Guardian. “Dreams pretty stubbornly and persistently remind us of hidden aspects of ourselves that we might do well to integrate.”

About a decade ago, I met another dream worker named Louise Rosager at a friend’s New Year’s Day brunch. She had also studied with Gillingham. In a past life, Rosager was a ballet dancer and actor in Copenhagen, but after moving to L.A. in 2009, she started developing television series (she’s one of the executive producers behind the Shakespeare drama “Will”). After five years of studying with Gillingham, Rosager became curious about the intersection between dreams and writing and decided to become a dream work teacher herself.

On a midsummer day in 2021, as L.A. emerged from pandemic closures, Rosager held a class in the backyard of a friend’s home in Venice. Starting with mat work, Rosager led us through writing prompts, breathwork and gentle movement, easing us into confluence with our dream material. In the second half of the class, by random draw, my dream was selected for staging. In other words, my classmates were asked to act out my dream, with me as director. I had first staged a dream in this way in Gillingham’s classes, but I’m never prepared for what unfolds.

The author has made a career out of navigating unstable ground. His latest book, “I Finally Bought Some Jordans,” is out next week.

Watching your dream play out before your eyes in waking life is like inhabiting an alternate reality: hair-raising, confronting, wrecking. Dream work is the opposite of escapism. It’s also nourishing. As Rosager talked me through the staging of the dream, a massive tree appeared in my mind, which I hadn’t noted in the original retelling of the dream. Had the tree been there all along, waiting for me to seek its wisdom? Had it grown with me over the years, or had I grown with it?

Three years later, in preparation for our conversation, I revisit this dream with Rosager, as she leads me through a second dream work session. “Artists want to bare their soul,” she tells me. “The thing we’re making becomes the context through which we can safely do that. It is us but not us.” Dream work offers no answers. It offers something harder to come by: wonder.

Amy Raasch: We tend to hear that the dreamer is every character in their dream. But many wonder, as I did with the dream involving a visitation from my sister two weeks after she died, whether dream figures have come to connect with us in some way or if it all comes from the psyche. How did you come to your understanding of dreams?

Louise Rosager: I was having extremely powerful dreams in my late teens and early 20s. They seemed so undeniable; I had to address them somehow. I used a technique called active imagination, which is essentially automatic writing with a dream character. You are yourself, but you’re allowing the dream character to take your pen and write answers to your questions. I was an actor at the time and dreams would often come in parallel to the characters I was working on. I intuitively had the sense they had something to offer my ability to bring that character to life.

AR: When “talking” to a character or object from my dream in this way — a red phone, a broken piano — I find that as long as I keep the pen moving on the page, there’s always an answer.

LR: It just comes through. Oftentimes, people who have never worked on a dream before will come in to work with me and say, what if it doesn’t work? What if nothing comes? It always comes. I drop them into the dream again, help them breathe a little bit, loosen up the body to dissolve the edges of judgment and ego that we all have, and immediately, I’ll ask, where is the broken piano? And they’ll point to it. They’ll know where it is in space. The dream is so present. It’s as if it’s existing the whole time. All you have to do is open some kind of doorway to it.

AR: Do you think the dream exists before the dreamer dreams it?

LR: Whether it’s in the psyche, or some part of the universe that we don’t know anything about — people call it source, God, dreammaker — something makes these dreams for us. There will never be another person in the world who will have the same dream you’ll have tonight. And the information in those dreams is truly tailor-made for you.

AR: How did you transition from being a young actor in Copenhagen, working intuitively with dreams, to teaching this work?

LR: I moved to New York, I got into Shakespeare. When I moved to L.A. in my mid-20s, I met Kim Gillingham, an extraordinary acting teacher who uses dream work as a portal into the unconscious, into things you don’t know about yourself. You close your eyes and work in a very embodied way with your dream images for sometimes up to two hours. When I first worked with her, it was this sense of, OK, this exists. Dream work was something other people were doing and having extraordinary results creatively.

AR: But as you’ve developed as a teacher, you’ve taken it in your own direction.

LR: Yes, after working with Kim, I studied with Stephen Aizenstat at Pacifica Graduate Institute. Stephen’s approach is that dreams are living, autonomous worlds and figures and landscapes. They show up to teach me something, but they also need something from me. Could it be the dream figure is dreaming me as much as I’m dreaming them? What if, with no agenda, I’m in relationship with this figure the same way I’m in relationship with people in my life?

AR: And in relationship with scripted characters?

LR: I work with people’s written characters or characters they’re playing onstage the same way I work on a dream: Let’s meet this living image from the perspective of archetype. If I’m playing Juliet, I would like to think she should be played a certain way, because that’s who she is. But if I allow that image to truly work on me, she might be a completely different Juliet than I or anybody else has ever imagined.

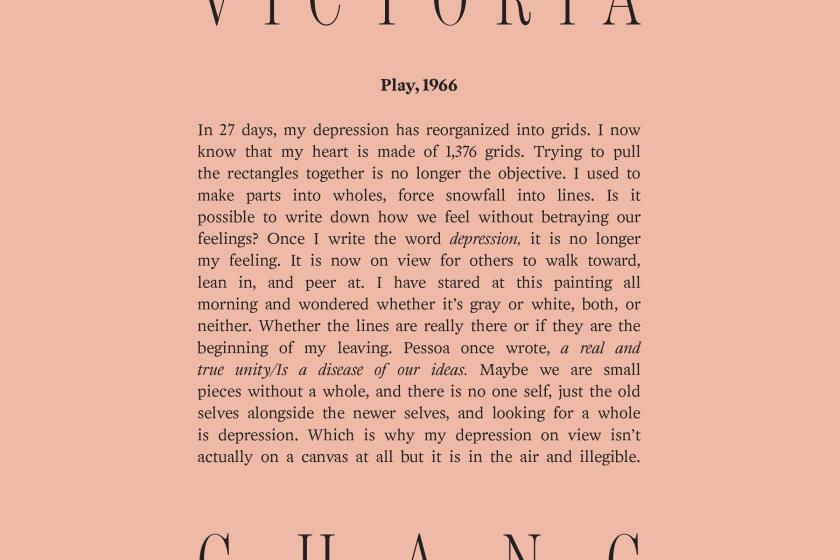

In her poem “Play, 1966,” from her forthcoming collection “With My Back to the World,” Chang observes the effects of depression like a painting on a wall.

AR: Can you describe the process of letting the image work on you?

LR: Step 1, get out of the ego consciousness around what’s supposed to happen. That’s where I drop people down. I use breath work, gentle movements — just to discombobulate the body a little bit. Then I talk people into a place where they can begin to imagine into the world they’ve created. If I’m working with a dream, I say, “OK, enter the dream place again. What do you see?” Same thing if it’s a setting from your script. When you work in that way, details become clear that you didn’t know were there. Sometimes there are people in the room you hadn’t imagined. You can take it or leave it. If it doesn’t fit into the script, that’s fine. But the imagination is creating this world for a reason; let’s just allow it to be for a moment. And then I bring the character in. What’s the essence emanating from them? Where in your body do you feel that essence? Sometimes, depending on the person, I’ll say, “What would happen if you allowed some of that energy into your body, some of the thoughts they might have into your head?”

AR: You work with writers on structure and outlining as well as dream work. Do you consider dreams narrative?

LR: The narrative structure of a dream, like most TV shows and films, is basically a four- or five-act structure. Shakespeare plays are five-act structures. So the dream is usually constructed of four moments. The first, from a symbolic perspective, is your life right now. For example, in your dream, we first set up the space: Where am I right now? What do you see?

AR: The cabin, my sister’s place in Stillwater. A spare anteroom, a desk, a red phone. The phone rings. It’s my sister.

LR: That’s the second moment, the inciting incident — there’s something you need to see. In the third moment, it shifts; there’s a realization.

AR: She’s calling me from beyond the grave. And she’s so light. She’s a step ahead of me. I’m chasing her through the rooms, but I can’t reach her.

Rosager wears Silk Laundry dress, Everlane shoes, Elizabeth Hooper earrings and cuff.

LR: That’s that third moment: psyche or dreammaker saying you have to look at this and deal with it. And then there’s the fourth moment, which is what Jung called the lysis, where the energy of your life wants to go.

AR: When I first wrote down the dream, it ended, “empty hallway, sky.” But when we staged it, there was this massive tree in the center of the room, rooted beneath the house and growing out through the skylight.

LR: It was very distinct. It was calling for your attention. I would say that is the last moment of the dream. It has an element of unconsciousness, like in any dream. We wouldn’t get the dream if it didn’t. When I rush through the rooms and try to grab onto her, I don’t see the tree. I don’t see light. When I slow down, this last moment can unfold itself and a brand-new perspective on the situation can unfold. I can be in this light too, with this companion, old mother tree, which teaches me how to live in the world, from a more authentic place. That’s the arc.

AR: There’s a strong component of you talking us through the moments, creating a container that allows the world to flower. I could not have gotten there on my own, because the dream was already making my head explode.

LR: When I sold my first show to HBO, I asked one of the executives, “What’s your secret to all these great shows?” Well, he said, “I think my job is to hold a safe space for artists to bring out their best material. Everything else I do is my job as well, but that’s my real job.” And I thought, “OK, that’s going to be my job.”

AR: You’re currently directing veterans in a production of “Romeo and Juliet.” How does dream work intersect with teaching Shakespeare?

LR: We work with Shakespeare’s characters as if we’re working with dream characters. And we will treat the play as if it were a character because it is. Shakespeare plays are like big dreams. Big dreams for the culture. Joseph Campbell says that dreams are personal myths and myths are collective dreams. Shakespeare, because he is a timeless writer, has created myths for our modern world. You can tap into those plays as if they were dreams the culture is experiencing. And I think we’re moving more and more toward the late romances [“Pericles,” “Cymbeline,” “A Winter’s Tale,” “The Tempest”], which is great, because those plays are full of hope and regeneration and forgiveness.

AR: One of the things that’s so curious about this work is the sense there’s something in dialogue with me. I’m not alone, I don’t have to invent everything.

LR: I see this with my clients all the time; that sort of fundamental loneliness goes away. Over time, you build up a council of figures that will be there for you in any situation. They can be figures from dreams, or figures you write, but you’re helping each other the whole time.

AR: We recently revisited my dream after a span of years. I was wary of returning to that deep grief, but it was all about the tree, which uprooted itself and floated into space — it had a wise but cheeky vibe.

LR: That tree is a portal. People will tell you that you can’t learn inspiration; you have to wait for it. I don’t believe that. I think the dream work is the inspiration. If you practice dream work the way you practice form and structure, you’ll be inspired the whole time. It’ll come to you because you’re open.

Producer: Mere Studios

Makeup: Daphne Chantell Del Rosario

Hair: Marilyn Lizardo

Styling Assistant: Alexa Armendiz

Amy Raasch is a Los Angeles-based writer, actor and performing musician. She holds a BA from the University of Michigan and an MFA from Bennington Writing Seminars. She writes about what haunts us.