“I can’t sit through a jazz concert.” Not the kind of admission you might expect to hear from a Grammy-nominated multi-instrumentalist, rapper, singer, engineer and producer known for his genre-bending prowess rooted in hip-hop and jazz. But when Terrace Martin, L.A.’s native son, gets going, he’s not one to hold back. “A lot of the time, most jazz artists are so into their thing that there’s a disconnect with the people and the crowd. No one is moving,” he continues, before passionately elaborating:

“When you look at the old pictures or listen to grandparents — Black people — talk, jazz was about making everybody feel good and smile. People danced; it was responsive. It wasn’t about looking at people like they’re in a motherf—ing museum, like this upper echelon of this hierarchy of art. So when I say I can’t sit through a jazz concert, I can’t sit through anything that doesn’t connect with me or the person next to me. I’m all about making little Black kids feel good about life. I want to give them something to look forward to, something to dream for, something they can get involved in, grow with and become. If I’m not doing that, what the f— am I doing?”

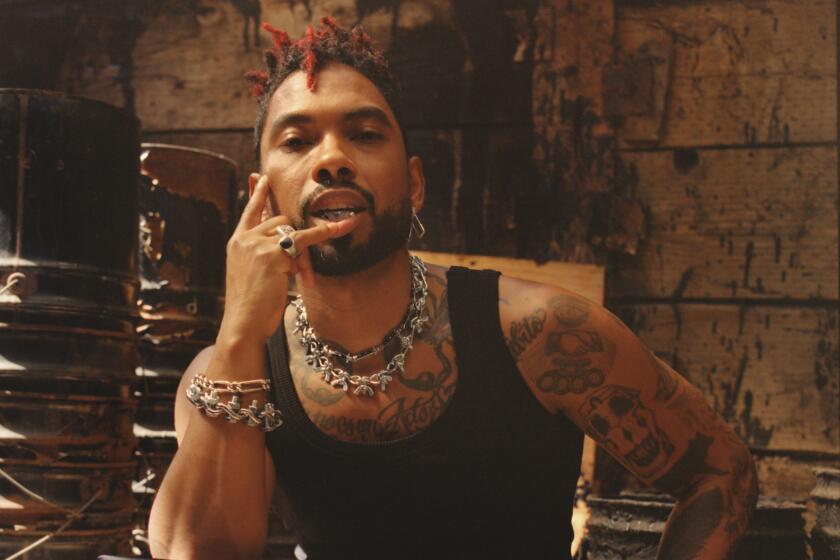

Martin is focused when listening but explosive when he speaks. He talks with exaggerated arm movements, charting his course between topics. He’ll begin with something straightforward, like the idea behind his label (“I wanted to create an atmosphere…”) and connect that to a little-known bite of culinary folklore (“Black folks — we love different things. That’s why we came up with the turkey taco…”), before finishing with thoughtful cultural commentary (“I feel like we got one of the only welcoming cultures that really welcome you in…”). His movements get most lively when talking about three things: music, weed and the Black men who guided him on his path.

He counts among his influences the legend Herbie Hancock, jazz apostle Miles Davis, hip-hop producer and emcee Q-Tip (whom he refers to as the “Master Teacher”) and Bay Area rapper Mac Dre, as well as the men who protected the blocks he grew up on. Martin is a keen scholar of craft; he’s studied many artists and steeped himself in different musical techniques, each of which he’s distilled into a uniquely dexterous style. He’s a type of sonic Optimus Prime. “What separates Terrace from other producers is he has such a well-versed and wealth of knowledge in different genres of music,” says longtime collaborator and friend Robert Glasper.

You’re always writing lyrics in your head. On ‘An Orange Colored Day,’ the L.A.-based singer shows what it looks like to get them down.

At 44, Martin is only gaining momentum. Your finger honestly gets fatigued scrolling his Discogs page. His career is littered with behind-the-scenes achievements that include landmark works like Snoop Dogg’s “R&G (Rhythm & Gangsta): The Masterpiece” and Kendrick Lamar’s “To Pimp a Butterfly.” He’s been a key player in legendary groups like the West Coast Get Down; Dinner Party, with collaborators Kamasi Washington, 9th Wonder and Glasper; and R+R=NOW, a band assembled by Glasper that includes Chief Xian aTunde Adjuah, Taylor McFerrin, Derrick Hodge and Justin Tyson. The nuance of his sound is rooted in the many musical legacies he’s a part of, but it’s also a product of the principles and people who raised him.

“When people say, ‘Who is Terrace Martin?’ it’s hard to identify myself,” he admits. “I got to look up to so many people. I can’t find one or two cats.”

Martin was born to Rose McKinney, a songwriter and lawyer, and Ernest “Curly” Martin, a jazz drummer, on Dec. 28, 1978. He grew up an only child in South Central in a middle-class household that cultivated expression and oozed music. He started playing piano at about 6 years old, and some of his earliest memories are his parents’ wild New Year’s Eve parties that would draw the likes of Sly Stone, Ike Turner and Charlie Wilson. Martin describes his home as “a household of no judgment where art and life weren’t separated.”

Martin came up alongside a large extended family, which included his cousins Ronald and Stephen “Thundercat” Bruner, and close friends Kamasi Washington and Ryan Porter. Two legends would take the five of them under their wings: Billy Higgins, a prolific jazz drummer for Blue Note Records who co-founded the World Stage in Leimert Park, and Reggie Andrews, a songwriter and educator with platinum hit records who spent time instructing gifted youth in Watts. Andrews, who died last year, taught Martin about the salvation that can come from music. “He really flipped our brains. He told us, ‘Y’all wanna do art, ’cause that other s— is bulls—,’” Martin recalls. “So instead of taking up a .45, it was like, ‘I’m gonna use this horn.’”

Just before ninth grade, Martin picked up the alto sax and quickly began excelling at it. He played six to eight hours every day, studying under his godfather, saxophonist Stemsy Hunter, and soon began receiving the title of “teen prodigy” and attending jazz camps — where he met a young Steven Bingley-Ellison, aka Flying Lotus, and Glasper, a budding pianist from Houston. Martin’s talent got him the attention of talk show host Jay Leno, who gave him his first professional saxophone. In no time, Martin was studying, firsthand, the production and engineering techniques of DJ Quik and DJ Battlecat.

DJ Quik discusses legacy, L.A. music, Death Row records

He would also, while in his teens, meet Snoop Dogg, who co-signed Martin’s talent and launched his career into the hyperdrive speed it’s stayed in. One of his earliest production credits is 2004’s “Joysticc” by 213 (Snoop, Warren G and Nate Dogg), a synth-piano-bass blend that foreshadows the unique sound Martin was percolating. His debut solo project, “Signal Flow,” slithered onto the scene in 2007 with Martin rapping, singing, playing and producing with an incomprehensible features list of Snoop, The Game, Busta Rhymes, Problem, Kurupt, Too Short and more. During the majority of his 30s, Martin contributed to every Lamar album from “Section.80” to “DAMN.”; he compares the artist’s import to Duke Ellington in that “he made this whole s— crack open.” As of late, Martin has been producing for Herbie Hancock, an idol he now calls a friend.

Parenthood has long been a silent collaborator of Martin’s; he became a father around the time he met Snoop and now has five kids (the youngest is 6). “I’ve always had music that raised all the generations of my children out and charting, you know?” Martin says. “I’ve been able to see the direct connect between this mainstream untouchable artist and what that music does to a kid.” Perhaps this adds to the unshakable depth of Martin’s discography; he sees music’s potency impact younger generations in real time — a factor most artists don’t have from the early days of their career. It’s kept his music not only relevant but principled. His discography is a supplement to his fatherhood.

Martin is a multifaceted talent in the studio, as well versed in terms like “impedance” and “gain staging” as he is with microphones and composition. “Not only is he an exceptional musician and artist but also an incredible engineer,” Glasper says. “His understanding of the overall process is second to none. I always learn something new being in the studio with Terrace.”

With Martin you get “an amazing world-class composer, sound engineer and college-professor-level musicologist who knows more records than almost any DJ,” says Washington. “So you essentially get someone who knows what to do and how to do it in every way. He’s gonna tell you if it’s wrong and more importantly, when it’s right. Knowing when enough is enough is one of the most difficult parts of the creative process.”

Making difficult seem easy is Martin’s specialty. He grounds his dizzying, avant-garde arrangements with warm, familiar reference points. Take the album he dropped with Alex Isley in October, “I Left My Heart in Ladera.” Isley, whom Martin calls “the queen of L.A. R&B,” has a soft, gentle voice that feels like the ocean — undulating, deep, bobbing — until, every so often, a wave of bass-heavy synth crashes on you. Or a raucous bass line hooks you like an undertow. “I turned her vocal so high up, because I didn’t want to sacrifice that bass,” he says. There’s always something just beneath the surface of Martin’s music that keeps you alert, active in your listening.

My bond with Fred Moten spans a nation of Black music. The music of collective improvisation mirrors the relationships in your life and your relationship to your own many-layered consciousness.

Martin makes the sonically unexpected feel natural and necessary. “Curly,” Martin’s tribute album to his father, turns the studio into a pulpit with the jazz organ wizardry of the great Cory Henry. The harmony of drums, sax and organ might make you feel born again. “Nova” with James Fauntleroy sounds like Luther Vandross and Anita Baker had a Brazilian child. On “Devil’s Advocate” from the recently released album “sneek,” Gallant’s lilting croon ushers in Martin’s smooth sax while a sound like a banshee’s lullaby flurries in the upper register — in a good way.

One thing that sets Martin apart is his ear. He hears things that others don’t, makes connections others won’t. “I’ve known Terrace since I was 13 years old. He’s always been ahead of the pack and that hasn’t changed,” Washington says.

There’s an instance in Martin’s life that feels particularly potent, when multiple points in his personal story and his talent for novel production powerfully converge: “To Pimp a Butterfly.”

Martin had already been collaborating with Kendrick Lamar on both his previous albums. “TPAB” is in some ways Martin’s old friends meeting his new one. He explains the process in literal electric terms. Flying Lotus, Glasper and producer Sounwave’s frequencies build upon Lamar’s current. Time itself takes on the role of conductor to distribute their energies at the right time with the appropriate flow. Maybe it’s the engineer in him speaking this way, but it feels spiritual.

Here’s something about “TPAB” Martin says he’s never told anybody — including Lamar. At one point during production, Lamar asks Martin if he knows anyone who can do strings. Martin says, “Yeah, I got a boy who’s been doing it for years.” He then calls up Washington:

“Hey man, you ever done strings?”

“Once,” Washington tells him — for his own record. He plays part of his then-unreleased “The Epic.”

As soon as Martin hears one note of strings, he reports back to Lamar: “Kamasi does strings.”

Washington would end up composing the string arrangement for “Mortal Man,” the closing track of an album that demonstrated a level of complex musicality that listeners — fans and critics alike — are still deciphering. It’s a hip-hop record with funky beats, provocative time signatures, soul grooves, free-jazz interludes and psychedelic dips that maintains core elements of West Coast rap. Martin was a critical part of that sonic universe, contributing to eight of the 16 tracks on the album. It put his talents — and those of his friends — on the global stage and made everyone take note. “They ain’t never heard nobody playing like this,” Martin says. “I had never heard it.”

Martin launched his label Sounds of Crenshaw in 2016, a way to share what he hears with the world. The label is centered around artist-first deals and equal splits, the name a nod to the numerous types of sounds you hear when driving down the eponymous boulevard. It’s a playground for Martin, a home for the gamut of good music. “Snoop Dogg is a big reason I started Sounds of Crenshaw,” says Martin. “I wanted to make a label that sounds like his backstage.”

For 13 years, Martin was a member of his mentor’s touring band, often playing alongside Washington and Thundercat. That backstage was a welcoming, joyful space that Snoop engineered to provide genuine hospitality to folks. Eclectic music filled the air — from Curtis Mayfield to unreleased 2Pac to Jodeci to John Coltrane — and helped people reminisce, relax and get inspired. “I want to start a label and a movement and a whole world that felt like, I never want to leave,” Martin explains.

Since spring of this year, Martin (who can play drums and guitar in addition to saxophone and keys) has put out eight projects on the label that each have their own brilliance. “I could’ve gone faster,” he says. “I got slowed down by the way the system says you have to do things.” In addition to “sneek,” “I Left My Heart in Ladera,” “Curly” and “Nova,” he’s dropped “Enigmatic Society,” the latest genre-melding excursion from Dinner Party; “Fine Tune”; and “The Near North Side” with Calvin Keys (in November), a free-wheeling guitar-led romp with the 81-year-old legend. He even slipped in “Ornamental,” a holiday album, in December.

Having experienced the most spiritual growth of his life in the last year, the songbird from San Pedro is finally ready to fully share himself — and his first album in six years — with the world.

What gives a record its Sounds of Crenshaw mark is the bass. “The bottom end represents the truth,” Martin elaborates. “The bass to me is the attitude of a record, but it also represents the soul. Round, full, huggable, but gangsta. It represents that sensual yet protective side. I grew up with men that protected the neighborhood. So I’m just trying to paint that circle of love back into the world, you know? It’s all in that low end, in a bass line.”

That bass line love was publicly available in early November when Martin performed at the LA3C festival that took over downtown Los Angeles with a six-piece band — bass, guitar, keys, percussion, flute, drummer — and three of the slickest background singers I have ever seen. They might as well have been Vanity 6. He brought out Isley and Fauntleroy — “Nova” was nominated for a Grammy the day before.

Martin spent the set switching among the saxophone, synths, the vocoder and doing live production. He orchestrated moments of levity that had audiences hooting, hollering and laughing. But he also played conductor, moving around the stage to make small adjustments. At one point, midsong, he told the drummer to play with no hi-hat. At another point, he told everybody to stop and “let me just hear the bass” while he invited Isley to freestyle. Washington, who played the festival the day before, and Glasper, who played following Martin and brought him out during his set, perform similarly. Their shows are dynamic and responsive; the dictionary definition of a “phenomenon,” not the musty idea of “jazz.”

Martin sees himself as a servant to his community: A vessel for joy, healing and dreaming. Music is a secret code to unlock the marvel of the human spirit. “Art is the one place that we shouldn’t be controlled. Art is the one place that we should all be able to be free,” he says. “Life is so f—ed up — I mean, we alive; life is beautiful — but we go through ups and downs. Art is the one place that we can control the atmosphere. ... Art, for me, has always been the safe, free space. Art is free. I want to maintain that in my music. I want that to be a common thread.”

Grooming: Laura Dudley

Photo assistants: Amari Dixon, Cris Ian Garcia, Elena Rojas Garcia

Nereya Otieno is a writer focused on music, food and the arts as forms of storytelling. She is the co-founder of the Rising Artist Foundation and currently lives in Los Angeles.