This story is part of Image issue 17, “Offering,” a special gift from L.A.’s creative community to a city that seemingly has it all. Read the whole issue here.

Paul Mpagi Sepuya crafts pictures that feel as intimate and warm as they do formal and intellectual. His photos do what art does best: Offer an immediate jolt of both recognition and disorientation, and point toward a singular perspective — a voice, a vision. I’m tempted to say they are arresting images, or captivating, but then the involuntary connotations of those adjectives don’t seem to fit; better to say that Sepuya creates images that hold you. Images that give pause and invite reflection — not so much like looking in a mirror but very much like catching someone else, someone you care for, gazing into the mirror.

There are bodies, often fragmented, or obscured, or hinted at; the photographer himself is sometimes subject, as is the camera, as is the studio itself. I was lucky enough to visit that studio, and after looking at so many of his pictures, the space and its objects felt both familiar and somehow magically charged — the way some people feel when they spot a celebrity, I suppose — there they were: the enormous mirror on wheeled legs, the black drapery, soft and heavy; the oversize velour pillows, golden brown. I could imagine the models coming and going (Sepuya photographs people only whom he knows), the posing and the touching. Touch is another of Sepuya’s main subjects, sometimes instructive or guiding, sometimes erotic, sometimes it’s the finger on the shutter release.

I found Sepuya to be thoughtful and generous with his time. To each of my questions, he gave long, comprehensive answers. He moved gracefully from precise descriptions of technique and form, to influence and mentorship, to social and political issues, empire, sex and race, to the history of photography, to the welcome abundance of roses in L.A.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Justin Torres: When I look at this photo, in which the camera lens directly faces the viewer, I feel like the instant reaction is, “Oh, it’s me. I am the subject. There’s the camera. Here I am standing before it.” And then, because you have the presence of the smudges, one realizes, “Oh, this is a photograph of a mirror. This is a closed loop. It’s not about me.”

Paul Mpagi Sepuya: Totally.

JT: Why is it important to both invite the viewer to feel like they’re being objectified — or like they’re the subject — and also exclude, or reinforce that exclusion somehow?

PS: Any kind of invitation, so to speak, is secondary and not a part of what matters. When I started making the images with the mirrors, I didn’t set it up as a way to invite the viewer in — that’s never been a part of it. It was about being able to work with the kind of picture where the figure-ground relationship got kind of mixed up, but in relation to the unfolding of time, so that the recurring background of the images would be this sort of shifting and slowly changing space of the studio.

JT: The titles you’ve given the more recent pictures refer to the image file number, which instantly takes me to the world of digital production versus mechanical or analog production. Though your work is not manipulated digitally, right? You don’t do Photoshop?

PS: Yeah, it just “is what it is.”

JT: As a culture, we’re so inundated with manipulated digital images that with some of the more fractured images one might, at first glance, think: “Oh, this must be Photoshopped.” But again, on closer inspection, you realize it’s almost an optical illusion. And there’s something really gratifying about that discovery, about working out how the shot may have come together. But I wonder, why not Photoshop? Is there something about digital manipulation that you have an instinctual critique toward? Or a kind of allergy toward?

PS: I think it’s important that each work be a single exposure. That’s key.

When I was making the first “Mirror Studies” in 2014 and early 2015 — using the mirror as a surface to hold image fragments and reflect back the camera, studio and sometimes my own presence — people kept assuming the pictures were digitally constructed. And I was like, “No, each one is a single exposure.” Those were also shot on film; there was nothing in them saying that this was digital — you could see that the camera taking them was a Mamiya RZ. They were meant to be sequential as well. Because as you go across them, you start to see how time plays out in the studio in a different way. Each one was just called “Mirror studies such and such,” along with the initials of the person or people that it was structured around — so it might be like, “Study for JT With Roses,” “Parenthesis 1104”; that ‘1104’ is the 11th roll of film I’ve shot from the project and the fourth frame. So, you could see a process in which everything kind of moved through the space. That’s where it started off with the parenthesis; it was marking a sense of time passing but also emphasizing the single exposure. Then, when I switched to [shooting digitally] — it’s just much easier and more efficient — I began with that as well. Just: Here’s the file name assigned by the camera.

JT: It does signal this kind of temporal moment, like this is when the shutter snapped.

PS: Yeah, you get a bit of that in there.

JT: The other thing I love about your work is how queer it is. There are images where you have only a glimpse of some body or bodies — the subjects are obscured. You might see just a bit of leg, and you imagine so much about what else is there, what else is going on. You want to see the face, you want to see the body parts that aren’t visible. It made me think of going to sex clubs and how what is so sexy are the glimpses, oftentimes not having access to the full subject. And in the pictures, the way in which they’ve been fragmented, there’s something so erotic and sexually charged about that. How do you think about the relationship between sexuality, eroticism and the kind of high, fine art that you make?

PS: I was talking to a friend about the difference between cruising and a sauna or a spa or a sex club. With cruising, it’s just like a spider lying in wait for prey; it’s this sort of prolonged thing. Cruising I find interesting, conceptually, and I have friends who have these really meaningful experiences, but there’s a lot of waiting, the anticipation, and then a furtive encounter, and then it’s done. But in another kind of space — in the sex club or in the spa or in the orgy space — there’s kind of a circulation. There’s conversation, moving in and out; it’s much more of a social gathering. That’s the kind of structure I’m interested in in photographs — the creation of a space, a social space.

JT: I think what a lot of your work does, what makes it so sexy, it’s not necessarily the bodies — but the sense that it is very intimate. In the photos that have multiple people involved, you get the sense of people coming together in these moments of true intimacy and making something sublime. You get the sense that you are directing — you are leading; you, as photographer, are in control. In some of them, I can imagine the instructions you’re giving, or the curiosity that one of your subjects has about what you’re doing. I can almost imagine the conversation that’s happening in the moment of the photo, and all the previous conversations between subject and photographer that went into building the trust for this kind of exposure. I mean, that’s sex, right? You come together and try to make some kind of sublime moment, if possible.

I’m curious. When did you know — as somebody who does portraiture — the subject was always going to be somebody with whom you had intimacy? Because I’m sure that everybody would love to have their photo taken by you.

PS: No. I mean, some people are really shy — there’s always been friends who, even in the more traditional portrait sitting, might be very shy. Maybe it’s something within the last seven or eight years I’ve thought about more. Soon after undergrad, I stopped photographing people I didn’t know. I just started making portraits of friends — this new group of friends that I was making in Brooklyn — and family. Not everyone was gay or queer. At some point, I would ask pretty much anyone I was ever friends with to sit for a portrait, and I have hundreds of those. All of this precedes the studio too. It’s like, you start making something and no one knows where it’s going to be, and friends just sort of trust you and you make a portrait. It was the photos of the gay boys that started to really circulate in this image economy, and then people who saw those images wanted to be a part of that space — it was this weird moment where people I didn’t know would come up to me asking if I would make their picture or start telling me what they’ve sort of imagined. There’s like this fantasy that exists — this becomes sort of a stage, or a space, that may or may not be actually connected to the work. I kind of always kept that at arm’s length but have been using this kind of outward solicitation as context in recent work.

JT: I want to ask about the red-light pictures on this wall behind us. Where are these in the chronology of your work?

PS: These are from the last year and a half.

JT: So this is where you’re going?

PS: It’s one of the concurrent things. There are always multiple things.

JT: They’re fantastic. The red light is so charged — it’s such a metaphor. I’m curious, what was the moment of discovery when were you like, “Oh, this is working”?

PS: In my early photos, up until about 2010, I’d always used a strobe, a mono light, mostly because I was photographing those early portraits at odd hours around a day job. Then, when I did these residencies at the Studio Museum and Center for Photography at Woodstock, I started photographing with natural light for the first time. I’ve continued that for the most part — in the studio space that I’m in here, I’m always using a skylight. But just the fact of having a studio in one of these converted warehouse spaces in L.A. — it gets really hot in the summers, and it’s really hard to be here in the daytime. And then, in the winter, the sun goes down so soon. It was really limiting how I could make work. Because of full-time faculty work obligations, there were very brief windows of time when I could be especially productive. So I was thinking, how can I make work at night in the space when it’s cooled down a little bit and not use strobes? At first, I used actual photography safe lights, but they were too dim at 6 watts. My exposures were often 30 or more seconds. I was like, “Oh, I have these color-changing LED lights at home.” I just brought them here and dialed them into the hue of safe lights. I got some clip light reflectors from the hardware store and put them up on the stands I already had, and for a couple of months, I would come here at night by myself and just try seeing how it was to photograph under the red light.

Starting in 2014, I was making all of these snapshots — long exposures verging on abstraction, like the ambient red light in bars and clubs. I have this whole series of roses at night; moving back to L.A., I forgot how there are just roses everywhere. I was always taking these pictures on my iPhone of roses at night lit by car lights and that red glow, and then thinking about that and bodies — all of these things that were making their way into these pictures called “Exposures” from 2017, ’18, ’19.

In these new “Dark Room Studio” works, a lot of things are happening. There’s one photo of a friend just writing, there’s one where I’ve invited some people over and we see their bodies all blurry in a kind of sexy huddle. Or you can see people gazing into their reflection; there’s an image of someone sleeping. There are people photographing each other, there are people showing off. I wanted them to have this quality of monochromatic light. The important thing is that these images weren’t shot and turned into black-and-white and then layered with a red filter over them. Initially, people asked if they were processed images.

With this almost monochromatic image, produced as dye sublimation on a matte aluminum surface, I wanted them to have a viewing experience in relation to 19th century photographs. They’re not meant to faithfully reproduce the daguerreotype or metal plate print, but the print itself has a kind of illumination and works with light in a way that the bodies in those spaces are kind of attuned to.

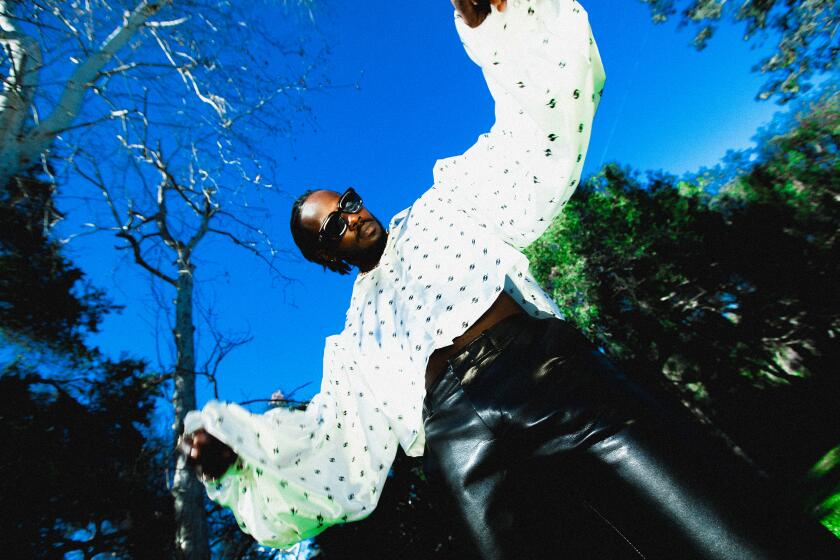

With a new EP and outlook on life, the L.A. artist is reaching toward his truest self.

JT: You’re talking about 19th century photography, and that’s interesting because I feel like it’s not just these more recent photos, right? I feel like I’ve come across a lot of your work where certain motifs pop up — the draping, the black curtains, the pillows …

PS: There’s all the stuff in the space.

JT: What’s that about? Where does that come from? Is it because you’re really interested in the emergence of photography itself?

PS: When I was at UCLA, I was interested in early modernist photography, the experimentation in the 1920s and ’30s, post-pictorialists like Florence Henri and also that same era of homoerotic photography. But part of it was thinking about the structure of photography — and this is what the mirrors allowed me to do — the centering of that device, the apparatus, and calling attention to the subject and the space and the operator of it in relation to point perspective — these are all things that I wanted to tie together through a different kind of origin point of Black subjectivity, homoerotic desire and queer social formations.

When I moved into this new space in 2021, it was a chance to consider how I wanted the space to be constructed. I had been in my last studio in the same building from the end of grad school in 2016 until spring of 2021 and needed a change. And because things were really slow with COVID, I was doing a lot of just looking at the history of photo studios. I was looking at a lot of these images of 19th-century studios and I was looking at depictions of Rodin’s atelier, looking at F. Holland Day’s photos, and then thinking about the history of portraits of Black people in these spaces; I was looking at the objects in the spaces. There was so much stuff that I was looking at, that I just started bit by bit collecting and sourcing little things. I’m not trying to reproduce a 19th-century photo studio, but it is everything from 1970s Persian and Afghan rugs and North African rugs, to actual antique walnut pedestals that come from a French artist’s studio from the 1870s. There are several African objects from the early 19th, late 18th centuries; there’s a 1980s marble pedestal and a reproduction of a Savonarola chair. There are these gardening tools from about 1910 that come from my basement. There’s a silver pitcher that I got from a neighbor at a yard sale. You know, everything just sort of together.

I didn’t have an agenda for what they’re supposed to mean. I’m never starting a project being like, “Oh, I know the conclusion, and now I’ll just try to make something to reinforce some preexisting idea that I have.” So I was just like, “OK, these objects are complicated, and I’m just gonna photograph with them.” But starting to then look at these historical photographs and thinking about these North American and mostly Western European photo studios — it’s the 1870s, it’s that moment approaching the peak of European colonization of Africa, Southeast Asia. All these objects that are being brought in, it’s also coinciding with a Neoclassical revival. All these things signify the imperial, colonizing reach. As I was photographing with them, I was thinking about how these objects can really create these forms that we’re still dealing with, in terms of racialized, exoticized bodies — in a sense, looking at the white bodies in those images, constructed as a form of difference and having access to but also dominion over all these objects that stand in for most of this world. I was thinking, “How do I work within that or play with it or kind of ask questions?” There are a lot of images that make use of ideas — visually, formally, conceptually — of racial difference. So it’s interesting making that work with friends, right? Within them, there is not a value judgment on them. It’s just like, “OK, I’m working with this space.”

Justin Torres is an assistant professor of English at UCLA. His second novel, “Blackouts,” will be published this fall. @justin_torres_books