This story is part of Image issue 13, “Image Makers,” a celebration of the L.A. luminaries redefining the narrative possibilities of fashion. Read the whole issue here.

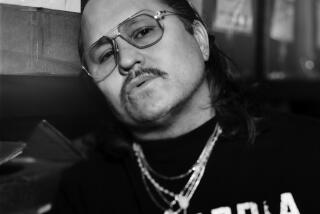

“It’s a lot more than fashion to me — I always feel like fashion is very secondary to what I do,” says stylist Marcus Correa. “It’s much more about storytelling, and really trying to reflect the identity of who I’m shooting with.”

I meet Correa at Tlaloc Studios, an artist-run studio in South Los Angeles, a space that has been meaningful to him since he moved to L.A. a couple of years ago. In the background, artists are busy collaborating on floor-to-ceiling paintings, on photo shoots. They stop by to say hi, exchange hugs. “I really feed off of other people’s energy,” Correa says.

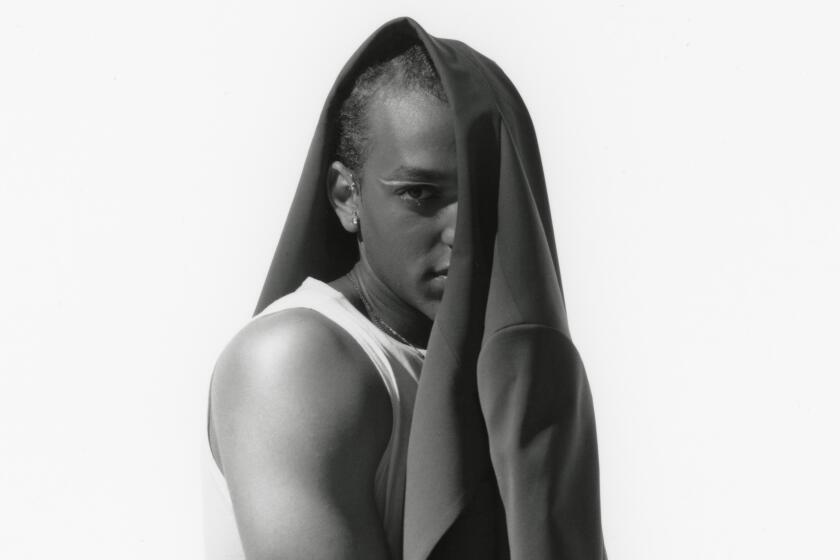

Last year, he produced his “Cut Deep” project in Tlaloc, a shoot he collaborated on with photographer Carlos Jaramillo that sheds light and love on Latinx hairstyles — fades, braids, mohawks and more — through the aesthetic of the classic barbershop poster. What started off as a shoot for eight or nine models ballooned to 30 — people from the community just wanted to help and be involved.

For Correa, it’s all about that warm energy. “I’ve been on a lot of sets with a lot of models and stylists and it’s, like, no shade to anybody, but it’s vapid or there’s no talking at all,” he says. “It’s just like that model is a mannequin, and that’s a very old school approach to fashion — I just can’t work like that, personally. If I can make people feel seen, tell their story in a way that they want to be seen — that’s everything for me.”

Right now, he wants to center Black and brown organizers — to give them “that celebrity treatment” that they deserve. Over the summer, Correa kicked off a series with Vogue profiling BIPOC climate activists. Working again with Jaramillo, as well as filmmaker Jazmin Garcia and Thomas Lopez of the Future Coalition, Correa is styling the activists in a mix of designer pieces and clothing that is personally meaningful to the subjects.

Correa, who grew up in north Denver, didn’t get into fashion through magazines or the fashion industry. “It was my cousins who taught me how to dress,” he says. From the curve of a hat to the button on a shirt, he remembers “so vividly, taking note.”

To Correa, fashion doesn’t mean anything without the specific stories that people bring with them.

Elisa Wouk Almino: How do you create images through clothes?

Marcus Correa: It’s the story, it’s the person, it’s the setting, always first — I don’t even think about the clothes until I think about that. For instance, even when I’m doing a runway, you know, it’s 45 models — I’m talking to every single one of them, gauging what their comfortability is, learning a little bit about them.

I like a hyper-realistic approach, where I take whatever a person’s personal feeling is and just really accentuate that and really blow it out. It’s always the person first, the story second, and the clothes are third to everything that I do.

EWA: Describe your process of dressing yourself.

MC: I think my process of dressing myself is really how I dress anybody else. I start with where I come from. I’m from north Denver. I’m from Sunnyside. So that’s kind of the base of it. And it’s not like I’m wearing a shirt that says that on it. It’s just all these little things that hold meaning to me. Like, I have my neighborhood all over my jewelry, I have it on my teeth — the silver jewelry, the Guadalupe pieces. And then having clothing that speaks to my culture without being so on the nose.

I really like stuff that fits well. But I don’t like anything that’s corny, too loud, in your face. I like to mix a lot of vintage pieces with designer pieces. I’m really crazy about textures and colors. It’s always wearing my homies’ brands, it’s a lot of Willy Chavarria. It’s a lot of Second/Layer. I try to pretty much either wear vintage, Black and brown designers or workwear, and I’d usually mix all three.

EWA: When we look at your closet, what do we see?

MC: I think what you’ll see is actually not as much as you think you would. I feel like I’m around clothes so much all day, every day, that when I get home, I very much have a uniform. Just, like, pants, color coordinated T-shirts.

Physical spaces in L.A. have always been sacred. Ashley S.P. and Jennifer Zapata see their concept shop as a vehicle for community and an homage to their friendship.

EWA: Do you have a favorite item?

MC: I’m obsessed with vintage T-shirts — I would say an EZLN shirt that I found at a flea market. Again, everything has to have meaning. I come from an organizing background. My family is part of the Chicano movement. There’s no better style than effortless. I have a pair of Willy Chavarria pants, which I feel very comfortable in. Those are my favorite baggy pants. I have this Bronco sweater from like the early ‘80s that fits perfectly and is just so intact. Or this vintage hat that I have — this is my dad’s from the ‘70s, he’s had this forever. I literally just stole this from him — I’ve stolen a lot of clothes from my dad, for sure.

EWA: Are there any specific styling concepts that you’re really into?

MC: I think the one specific thing — and anybody I work with probably hates me — but I’m so specific about the break on pant legs, the way pants sit on a shoe is like the most important thing to me in the world. I really, really love noticing how the pants stack, or really understanding how a waist fits, how his shirt fits just oversized, like really dialing in on the silhouette. I think, for me, it’s one big thing understanding people’s body types and what fits them where and how. When we do the runway rehearsal, it’s, like, 45 models, and I watch each one of them and I make notes of, like, OK, this shirt is falling this way, we need to tuck this — noting things down to, literally, underwear. Or thinking of things that I’ve seen before on the streets and replicating that. Really small details down to how a shoe is laced. I will get out of bed for that.

EWA: What have you seen in the streets of L.A. that you’ve wanted to replicate? Where were you?

MC: When I look at references, I’m not looking at runway photos or fashion photographers, I’m always looking at documentary photos. I do it on my day off, but I almost consider it like research and development. In L.A., I’m going to the swap meets. I’m going to Alameda, I’m going to Santa Fe Springs. I think one thing, for me, especially now with Chicano culture being so trendy, is just really understanding how that looks now — because it looks totally different. I love going out and seeing what these younger kids are wearing, like True Religions with Jordans and a bowl cut. They look like Nas in the ‘90s meets Chalino. The way they layer feels so effortless.

I don’t love that classic curation. I don’t want to pick up a copy of Vogue and try to replicate that, ever — that’s the opposite of what I want to do.

EWA: You were a model before you were a stylist. Did that influence your approach?

MC: I’ve been styled in things I felt really uncomfortable in. And I’ve seen pictures of myself looking very uncomfortable. And so I know what it’s like to walk a runway, I know what it’s like to stand in a presentation or get pictures taken when you really don’t like it. And so, when I work with models, I’m checking in, asking: Do you like this? Do you feel comfortable? Because it absolutely shows every single time.

EWA: Anything else that’s particular to you and how you work?

MC: I street cast almost everybody. Again, no shade to models, no shade to celebrities — kinda shade to celebrities — but I would much rather shoot with real people. A lot of people I shoot with are just homies.

The biggest thing I would say that I want to do with my work is explore masculinity and break down the toxic masculinity that I grew up around. And the No. 1 thing I want is [to see] my communities represented in fashion. And I know that people say that, but I really, really want to change the standard of beauty. That’s my No. 1 goal. When I look at an old magazine, it’s so hard for me to pull references because I can’t stand the way people would dress, I just can’t stand who was centered. I look at people from my community and those are the most beautiful people.

More stories from Image