L.A. Icon Otis Chandler Dies at 78

Otis Chandler, whose vision and determination as publisher of the Los Angeles Times from 1960 to 1980 catapulted the paper from mediocrity into the front ranks of American journalism, died today of a degenerative illness called Lewy body disease. He was 78.

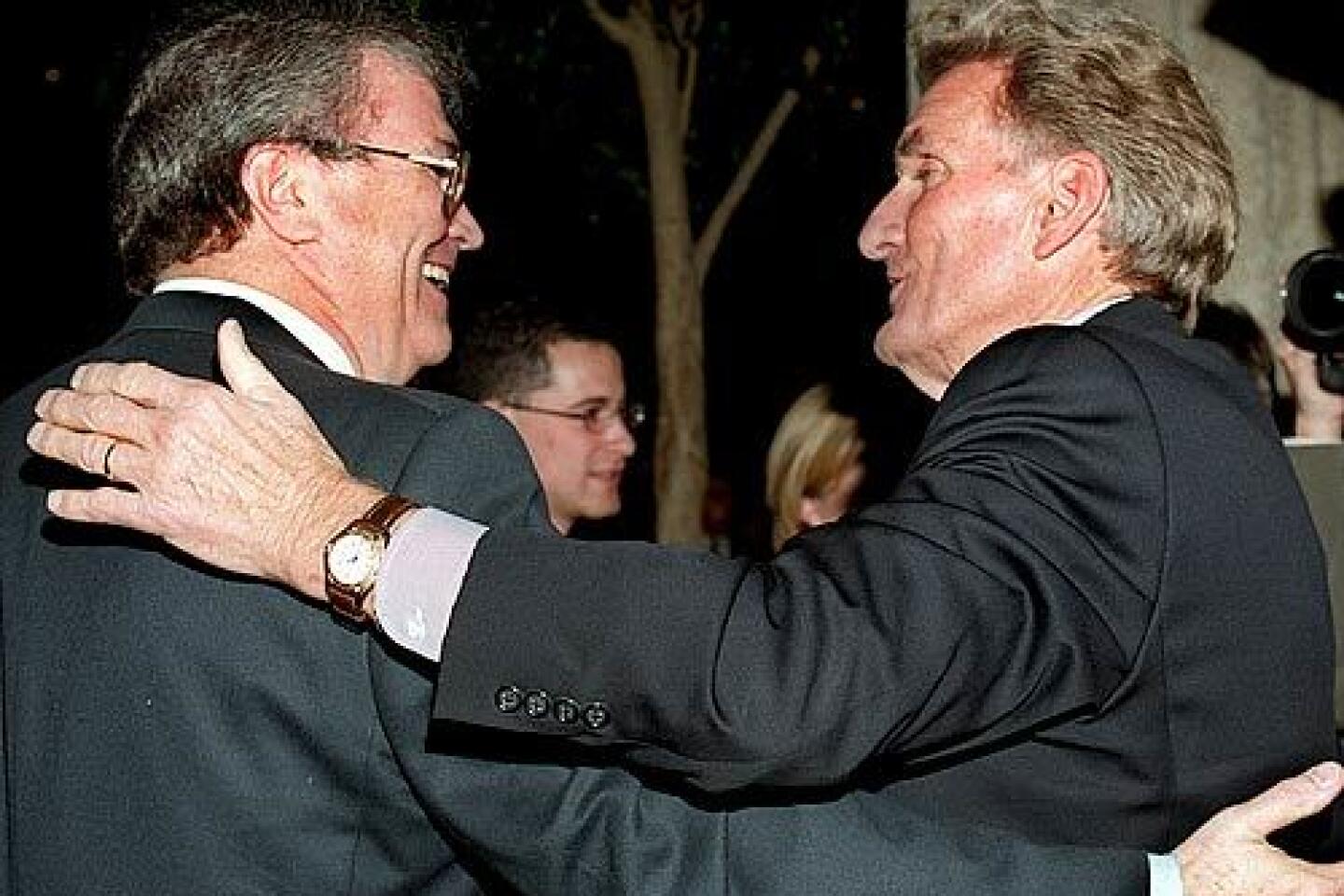

Chandler died at his home in Ojai about 4 a.m., according to Tom Johnson, a former publisher of The Times who was acting as a spokesman for the family. Chandler’s wife, Bettina, was with him. Other family members had gathered at the Chandler home.

“Otis Chandler will go down as one of the most important figures in newspaper history,” said Dean Baquet, editor of the Los Angeles Times. “He built a newspaper that was as great as the city it covers. He set his sights on a goal — making The Times one of the two or three great American papers — and he pulled it off.”

Lewy body disease is a brain disorder combining some of the most debilitating characteristics of Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases. Victims suffer from severe dementia, as well as the stiffness, tremors and impaired movements characteristic of Parkinson’s.

FOR THE RECORD:

In an earlier version of this article, the date of the Helsinki Olympic Games was incorrectly given as 1948. The Games took place in 1952. Also, the name of Otis Chandler’s first wife was incorrectly given as Marilyn Brandt. It is Marilyn Brant. —

The disease is known for its fast progression. Chandler was diagnosed seven months ago, although doctors had determined about a year earlier that he was suffering from some form of dementia, his wife said. As recently as September, Chandler appeared fit, aside from a knee injury, and was lucid enough to sit for an interview and give a visitor a guided tour of his classic car and motorcycle museum in Oxnard.

Chandler was the great-grandson of Gen. Harrison Gray Otis, the blustery Civil War veteran who bought part-ownership of The Times in 1882, a year after it began publication, and was its publisher for 35 years. Chandler’s grandfather and father followed Gen. Otis in the publisher’s chair. The Chandlers had no rival as the most powerful family in Southern California. They owned vast landholdings and used their influence with elected officials and the business elite to shape the region’s development.

But it was Otis Chandler — a world-class shotputter in college and a fierce competitor in every arena he entered — who took charge of a paper that for decades had generated almost as much ridicule as revenue and transformed it into one of the best newspapers in the country. He also made it more profitable than ever.

“No publisher in America improved a paper so quickly on so grand a scale, took a paper that was marginal in qualities and brought it to excellence as Otis Chandler did,” David Halberstam wrote in “The Powers That Be,” his 1979 book about the news media.

“You cannot overstate the importance of Otis Chandler’s impact on the Los Angeles Times, the newspaper industry and all of Southern California,” said current Times Publisher Jeff Johnson (no relation to Tom Johnson). “He was bold in making changes and investments in the paper that transformed The Times into a world-class news organization.”

“Otis was a giant in every way,” said Donald Graham, chief executive officer and chairman of the board of the Washington Post Co. “The paper you are reading is his monument. By his strength and by his judgment of good journalists, he was of unique importance in the history of the Los Angeles Times.”

During Chandler’s 20 years as publisher — and five subsequent years as editor in chief and chairman of the board of The Times’ then-parent company, Times Mirror — the paper won nine Pulitzer Prizes and expanded from two to 34 foreign and domestic bureaus. At the same time, it doubled its circulation to more than 1 million daily and for many years during and after his tenure published more news — and more advertising — than any other newspaper in the United States.

Chandler cared deeply about how The Times was regarded by East Coast opinion-makers, and more than 40 years after his father first took him to a national convention of newspaper publishers, he could still recall, with an edge in his voice, “how clear it was that The Times was regarded as a bad newspaper from a hick town.”

That perception embarrassed Chandler, and when he took over as publisher a few years later, it became the driving force behind his commitment to remake The Times.

In 1999 — almost 20 years after he left the publisher’s office and with no official ties to the paper anymore — its standing in the national journalistic firmament was still so important to him that he emerged from a largely self-imposed exile and issued a strong denunciation of top Times and Times Mirror executives. He thought they had committed transgressions that jeopardized the reputation and credibility he had worked so diligently to establish.

Many at The Times hoped that in the aftermath of that re-emergence, Chandler would use his moral authority to help reverse what he — and they — saw as the declining fortunes of the paper.

But by then, he had so little real power — and so little influence with the members of his family who controlled the paper — that when they decided four months later to sell Times Mirror to Tribune Co. of Chicago, he said he hadn’t even known about the negotiations until he heard “rumors, nothing more,” two days before the deal was consummated.

He was also so disenchanted with the management of Times Mirror by then that, to the dismay of many, he not only didn’t fight or even criticize the sale but instead embraced it as “a very positive move a perfect fit a win-win situation.”

Surprising though it may have been, that behavior — the initial reluctance to question his successors; the cheerful acquiescence to the sale — was very much in keeping with a lifelong pattern.

No Autocrat as Publisher

Chandler was never a meddler or an intruder. He hired the best people he could find and gave them the freedom, the resources and the challenge to take a newspaper that had been mocked as partisan, parochial and inferior and turn it into a publication that could no longer be sneered at.

“I never had him second-guess me, ever,” said William F. Thomas, The Times’ editor from 1971 to 1989. “He’d put you in there, and he let you do it — and if you weren’t performing, out you went.”

Chandler changed The Times so dramatically and became so identified with the paper that when he left the publisher’s office at age 52, and again when he relinquished his corporate titles five years later, employees at The Times and Chandler’s peers throughout the industry were both stunned and puzzled.

“Everyone wondered why, at so young an age, he would step away from something that he had had such an enormous impact in building,” Louis D. Boccardi, former president and chief executive officer of Associated Press, said more than a decade later.

Arthur O. Sulzberger, who was then publisher of the New York Times, said that although he initially shared his colleagues’ “surprise and disappointment” when Chandler left, “I later realized that I shouldn’t have been so surprised. As long as I knew him, Otis had an adventurous spirit and the courage to pursue it.”

Chandler had always had an active life outside the newspaper business, and in his final years as publisher, close friends and associates knew that the lure of those interests — combined with fatigue, restlessness, health problems and major changes in his personal life — were inexorably leading him away from The Times.

But it was fitting that his departure was so surprising to so many, for he had long been something of an enigma to his fellow publishers. Big, blond and broad-shouldered, Chandler looked more like a Muscle Beach habitue-turned-movie star than a corporate entrepreneur on a journalistic mission.

Sulzberger recalled decades later that he once walked into Chandler’s office “and found him hanging upside down in the doorway, like a bat. He said it was good for his back.”

Chandler was an exotic, at times mythic figure among the nation’s newspaper executives, most of whose exertions and excursions outside the boardroom were generally limited to golf courses and cruise ships.

“There is something about him that suggests if Otis Chandler hadn’t existed, Ernest Hemingway would have created him,” the Christian Science Monitor said in 1980. “When he strides out of a meeting to shake hands, it is like looking up at a California redwood.”

Anthony Day, The Times’ editorial page editor from 1971 until 1989, once said: “After I had been working for Otis for a few years, it occurred to me that I was working for a prince, a man who had been raised to be a prince.”

Chandler, he said, loved being publisher. “But he also had a prince’s sense of entitlement, a sense that perhaps I don’t have to do this every damn day,” he added.

Surely, Chandler was the only publisher of his — or any — generation to have been profiled not only in Time, Newsweek and Editor & Publisher but in such magazines as Road & Track, Strength and Health, and Safari Club — and to be depicted on the cover of the Atlantic Monthly in his bathing suit, riding a surfboard made of newspapers through the curl of a massive whitecap of dollar bills.

A go-anywhere, ride-any-wave surfer for more than 60 years, Chandler also hunted big game on safaris, raced high-speed cars and motorcycles on official tracks and urban freeways and was always looking for new challenges, preferably those with some measure of risk.

“I like living on the edge,” he said in a 1999 interview, five months after his 71st birthday and two weeks after he suffered minor head injuries when he spun out in one of his Ferraris near the vintage-car and wildlife museum he owned in Oxnard.

By his own count, Chandler had at least half a dozen brushes with death over the years, and that didn’t include his bout with prostate cancer in 1989 or his mild heart attack in 1998.

While he was hunting in Mozambique in 1964, an elephant charged him, his wife and their guide. When the guide missed his shot and ran off in a panic, Chandler shot the elephant in the leg at a distance of 10 yards, deflecting the animal just enough to send it thundering past them.

In 1995, when he was 68, his motorcycle collided with a tractor in New Zealand, leaving him with part of the big toe on his left foot missing, another toe severely damaged and the rest of the foot largely numb.

His most serious accident came in 1990, when a musk ox trampled him in the Northwest Territories of Canada and he had to be airlifted to a hospital. Doctors said his right arm, yanked from its socket by the impact, would be virtually useless for the rest of his life.

“They said I might be able to lift my hand to my mouth, but just barely and only after two years and only if I exercised it properly,” he recalled. “They told me I’d have to learn to do everything left-handed.”

With characteristic tenacity, Chandler exercised the arm rigorously, and six months later he could lift it over his head. Ultimately, he was able to do everything right-handed, he said, “except serve hard in tennis.”

Not Pampered, Never Effete

Born in Los Angeles on Nov. 23, 1927, Chandler was the only son of Norman Chandler and Dorothy Buffum Chandler. Although Halberstam would later say, “No single family dominates any other region of this country as the Chandlers have dominated California,” Otis had a far-from-pampered upbringing and was never a man who could be described as effete.

“He used the same tone of voice with the president of the United States and the guy who came to change the lightbulbs in his office,” said Donna Swayze, his executive secretary from 1962 to 1988.

John Thomas remembers meeting Chandler — and not knowing who he was — when Chandler took one of his Porsches to the auto dealership where Thomas worked as the parts manager in the late 1960s. The two men introduced themselves as “J.T.” and “Oats” (Chandler’s longtime family nickname), struck up a conversation about motorcycles and soon began dirt-biking together.

“When I asked what he did, he just said, ‘I work at The Times,’.” Thomas recalled. “But after about 18 months, I accepted an invitation to his house for dinner, and when I drove up to this huge mansion in San Marino, I thought, ‘Holy cow!’ When I got inside, I said, ‘Well, just what do you do at The Times?’.”

Only then did Chandler tell Thomas about himself and his family. Despite the enormous difference in their socioeconomic status, the two remained close friends for more than 30 years.

When Chandler was growing up, he lived with his parents on a 10-acre citrus ranch in Sierra Madre. His father, publisher of The Times from 1944 to 1960, had worked in the fields of the family’s Tejon Ranch when he was a boy, so he saw no reason to spare his son from physical labor or spoil him with money.

Otis shoveled fertilizer for the family fruit trees at an early age and was kept on such a modest allowance that even when he went to college, he later recalled, “the most lavish transportation I could afford was half-interest in a secondhand motorcycle.”

For a time, when he was young, Chandler rode a bicycle several miles to and from the Polytechnic School in Pasadena.

But he was hardly unaware of his family’s powerful position. As a boy, he would stand alongside his father and grandfather at Hollywood Cemetery (now Hollywood Forever) in annual memorials to the victims of a bomb blast that wrecked the Times building in 1910, killing 20 workers.

The explosion was blamed on union militants, and, Otis once said, “I was raised to hate the unions.” (He later mellowed on that topic, although he always opposed unionization at The Times.)

The most traumatic experience of Chandler’s childhood — one that assumed mythic proportions as he grew toward adulthood — came when he was 8.

In the midst of a horseback riding lesson, he was thrown hard to the ground. His mother scooped him up and rushed to the hospital, steering the car with one hand and holding his hand with the other, frantically searching for a pulse.

When doctors said Otis was dead, Mrs. Chandler wailed, “My son is not dead!” She picked him up and raced to another hospital, screaming all the way there, “Otis is alive, Otis is alive!”

On arrival, she encountered a doctor she knew, and he revived the boy with a shot of adrenaline in the heart.

Recovery was slow but complete, and it was during that period of recuperation, Chandler said many years later, that he “did a lot of thinking and somehow developed my competitiveness.”

When he was a little older, he set up his own backyard basketball backboard and high-jump pit, and practiced both sports, by himself, hour after hour. He also began to develop a love of speed and once had to do a stint in traffic school after getting a speeding ticket on his bicycle, he said.

Chandler started prep school at Cate, in Carpinteria, but his parents thought he’d find a greater challenge and broader perspective back East, so after a year they transferred him to Phillips Academy in Andover, Mass.

He was initially miserable; the other students all seemed richer, better-educated and more sophisticated. Southern California was considered a cultural backwater, and despite his family’s vast wealth and power, Chandler felt like a hick.

“Nobody had ever heard of the Chandlers,” he said later. “I was strictly a tall, skinny blond kid from California.”

He was skinny all right — 6 feet 1, 155 pounds — but he played varsity soccer and basketball, high-jumped and ran the mile, and his successes gave him an identity.

Still, he wanted to be bigger and stronger, so shortly after graduation, he took up weightlifting. By the time he enrolled at Stanford University in 1946, he weighed about 200 pounds.

His Stanford roommate, Norman Nourse, suggested that he try the shotput — throwing a 16-pound iron ball. Chandler immediately excelled, breaking the school freshman record with a toss of 48 feet, 761/47 inches.

Bulked up to 6 feet 3, 220 pounds as a senior in 1950, when he was captain of the track team, he put the shot 57 feet, 63/47 of an inch, to win the Pacific Coast Conference championship. He finished second in the nation, third in the heavyweight division at the national weightlifting championships that year.

His Biggest Disappointment

Two years later, he was considered a cinch to be one of three shotputters on the U.S. team for the Olympic Games in Helsinki, but he sprained his wrist before the tryouts and had to pull out — “the biggest disappointment of my life,” he recalled almost 50 years later.

Chandler liked the shotput and weightlifting, he once said, because they were individual sports, and he could be judged on his own merits.

“I liked to make it on my own in whatever I accomplished,” he told an interviewer. “No one could say that the team carried me or that the coach put me in because my name was Chandler.”

He sought largely solitary recreational activities throughout his adult life — surfing, lifting weights, racing, cycling, hunting. He was, in general, something of a loner, a trait he traced partly to “spending my young years on that ranch in Sierra Madre, a little remote, rather than on a neighborhood street with a lot of kids.” Asked repeatedly in one interview to name his best childhood friends, he came up blank.

Many people found him a bit distant — cool, controlled, difficult to know well — and these qualities became more pronounced as he matured and increasingly tried to escape the burden of being a Chandler.

After graduating from Stanford, he tried to enroll in an Air Force training program. He was turned down because he was 17 pounds heavier than the maximum allowed for jet pilots, so he starved himself and quickly lost the weight. He was rejected anyway; his shoulders and hips were still too big to fit into the cockpit of a jet.

He spent 1951 to 1953 on the ground in the Air Force, supervising sports and acting as co-captain of the Air Force track team at Camp Stoneman in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Growing up, Chandler had often said he’d like to be a doctor, although he later conceded, “I was never an outstanding scholar.” When he left the Air Force in 1953, he had no clear sense of what he wanted to do with his life.

He had married his college sweetheart, Marilyn Brant — having proposed to her on his 23rd birthday on the seventh hole of the Pebble Beach golf course — and they had a baby boy (Norman, after Otis’ father) but no plans and no substantial income. Like his father, who had also been kept on tight purse strings by his father, Otis often split the bill with his fiancee or let her pick up the tab when they dated.

The Times, he would later say, was very much in his blood even then.

As a boy of 5 or 6, he had frequently accompanied his father to the office and slid down the chutes that were used to drop papers from the pressroom to the delivery trucks.

In college, he had sometimes worked summers at the paper, most often using his physical strength to move printing plates and other heavy items and equipment. When he went home after his time in the Air Force, though, he didn’t envision journalism as his life’s work.

The night he arrived home, his young family’s possessions crammed into a used station wagon and rented trailer, his mother and father welcomed him enthusiastically.

The next evening, a Friday, his father — “grinning like a Cheshire cat,” Chandler would always remember — handed him a sheet of paper. On it, neatly typed, was a seven-year “executive training program,” scheduled to begin that Sunday night.

“I said something about wanting a week’s vacation first, but he wouldn’t hear of it,” Chandler said. “I started work right away, on the graveyard shift, midnight to 8 in the morning.” He was a pressroom apprentice, at $48 a week, the equivalent of $356 in today’s dollars.

He gradually worked his way through every department at the paper: production, circulation, the mailroom, mechanical, advertising, the newsroom.

Most of his early jobs in the training program were just that — jobs, “a grinding routine,” he later said — and because his father wanted him to have as many Times experiences (and meet as many Times employees) as possible, his schedule was constantly changing.

“I’d work the graveyard shift for a week, then spend a week on days, then a week on the swing shift, then back to the graveyard shift,” he recalled.

Once he started as a reporter, though, he began to feel different about a career at The Times.

“It was a watershed experience,” he said. “I loved being a reporter. That’s when I decided this was the business for me.”

Chandler was no typical rookie. From the start, he wrote periodic first-person columns, prominently displayed in the front section of the paper, musing about the life of an athlete or the quirks of an outboard motor. He wrote offbeat feature stories, such as one about the people who feed sharks at the aquarium. And he wrote an exhaustive, if somewhat ponderous, seven-part series about the treatment of mentally ill children.

He was also the only reporter, rookie or veteran, whose name regularly appeared in both the Sports section, which chronicled his continuing exploits as a competitive weightlifter, and in the society pages, where his attendance at various black-tie events always rated a mention.

He also showed his father skills that went beyond the reportorial.

In 1948 the Chandler family had started a second newspaper, an afternoon tabloid called the Los Angeles Mirror, and as part of his training program, Otis worked there too. As he did in every posting at The Times, he filled notebook after notebook with his thoughts on possible improvements.

The Mirror was losing $30,000 a week, and Otis sent his father a confidential memo urging that a strong business manager be hired. He also complained that the paper’s editor and publisher “never try to come up with new ways to cut the deficit. Instead they always find new ways to spend money.”

Norman Chandler was delighted by this practical evidence that Otis had absorbed his childhood lessons of prudence and thrift. Soon there was talk of Otis becoming publisher of the Mirror when he finished his training program — most likely as one of the final steps before he became publisher of The Times. But the Mirror continued to falter, and his parents decided they didn’t want his first command to be that of a sinking ship.

Otis, meanwhile, still had no idea what his mother and father had in mind for him.

“After a year or so in editorial, when I told my dad that I’d just like to be a reporter, he said, no, I had to go on to other departments,” Chandler said. “He said I had to be well-rounded and implied that it was so I could ultimately take some executive position. But he was never specific, and the word ‘publisher’ was never mentioned.”

In October 1957, continuing his climb into the executive ranks, Chandler was named special assistant to his father. Two years later, he was made marketing manager of The Times. About that time, Otis began telling Nick Williams, the editor of the paper, the kinds of improvements he envisioned making if and when he had the authority.

Then, on April 11, 1960, Norman Chandler invited more than 700 people to a luncheon at the Biltmore Bowl ballroom in downtown Los Angeles, where he promised a “special announcement.”

On that wisp of a lure, the room filled up with the cream of the Southern California establishment: corporate heads, college presidents, prominent lawyers and judges, Los Angeles Mayor Norris Poulson, members of the county Board of Supervisors, former California Gov. Goodwin J. Knight.

There was an air of anticipation as the elder Chandler stepped to the microphone and said, after a bit of reminiscing, “I hereby appoint, effective as of this moment, Otis Chandler as publisher of The Times.”

Otis stood up, grinned and said, “Wow!”

He recalled almost four decades later having had “no inkling what my dad was going to say until an hour before the luncheon. I was just told to be at the Biltmore an hour early for a civic luncheon.”

Who Pushed His Ascension?

Most historians credit Otis’ mother — “Buff” to her friends and family — with persuading her husband to make their son his successor. Mrs. Chandler later achieved fame on her own by raising almost $20 million to finance the creation of the Music Center, a step that went a long way toward erasing the “hick town” image that Otis had long resented, and she was always keenly interested in the paper’s coverage of culture and society.

Otis himself offered contradictory explanations of his mother’s role in his promotion, befitting a mother-son relationship that had its share of paradox.

He once said that she had received — and sought — more recognition than she deserved for many changes at the paper, including his own rise, and that his father had long been underestimated.

“A few weeks or months after I became publisher, my mother told me, ‘I used to tell your father that I thought you were ready, but he wouldn’t listen to me,’.” he said. “.’It was three outside members of the [Times Mirror] board who persuaded him to do it.’.”

But in a letter to his mother 12 years later, Otis referred to her as “that person who made it possible for me to provide leadership to The Times,” adding: “It was a tremendous gamble for you to take on any young man of 32.” There was no mention of his father.

The truth probably falls in the middle. Some close to the family and the paper suggest that it might have been Mrs. Chandler who asked the board members to pressure her husband to step aside as publisher so he could devote his full attention to his chairmanship of the parent Times Mirror company, which was about to embark on a major diversification program.

About the same time, McKinsey & Co., a management consulting firm, was conducting another of its periodic studies for The Times, and it too recommended dividing the responsibilities of publisher and chairman.

Norman Chandler, then near his 60th birthday, saw the logic in the change. The only other possible publisher in the family, however, was Norman’s younger brother Philip, then general manager of The Times and a member of the Times Mirror board.

Other key members of the Chandler family wanted Philip to succeed Norman, wrote Marshall Berges in his 1984 book, “The Life and Times of Los Angeles.” But Norman “regarded Philip as something of a lightweight, not entirely competent to take an aggressive leadership role at The Times.”

As it happened, the consultants also recommended that, to ensure stability, the new publisher be capable of holding the job at least 15 years. Since mandatory retirement age for the publisher was then 65, that conveniently eliminated the 52-year-old Philip. And that apparently gave Mrs. Chandler the opening she needed.

Buff Chandler was the daughter of a prominent Long Beach family, owners of the successful Buffums department store. Her father had been mayor of Long Beach.

But in the social pecking order of the Southern California elite, she was seen as a cut below the Chandlers, and they never let her forget it.

They “never thought she was good enough to marry Norman, and she was out to prove them wrong,” her son said several years after her death. They never forgave her for her apparent role in Otis’ ascension over Philip.

His sudden elevation and his record as an athlete, not a scholar, at Stanford, led some members of the family (and their friends) to openly wonder if he had the intellectual capacity to run The Times.

But former Editor Thomas, who joined the paper two years after Otis became publisher, said that although Chandler was basically “a C-plus student his focus and tenacity made him an A-plus as a publisher or almost anything else he really put his mind to.”

(“Jesus, Bill,” Chandler told Thomas when he learned what the editor had said. “I was a B student.”)

Direct, decisive and at times startlingly frank in both his personal and professional lives, Chandler told people what he expected of them, and he didn’t have much patience with failure. When many top Times executives proved either reluctant to change or incapable of meeting his standards after he became publisher, he replaced 22 of 23 department heads within the first year.

Knowing that he couldn’t create a high-quality, widely respected news organization if he relied exclusively on wire service reports and his existing staff, he began hiring top reporters and editors from other major news organizations and opening Times bureaus around the world.

Chandler was just then becoming interested in big game hunting, and his approach to hiring was much the same: only go after the biggest and the best.

One of the first examples came in 1961, when The Times hired Jim Murray as a sports columnist. Murray had helped create Sports Illustrated and was one of its stars. As a Times columnist, he would become one of the most celebrated sportswriters ever.

In the next three years, The Times changed as perhaps no other American newspaper has ever done in such a short time. Bureaus opened in Tokyo, Rio de Janeiro, Mexico City, Hong Kong, Rome, Bonn, London, Vienna and San Francisco, at the United Nations and on Wall Street. Staffing in Washington and Sacramento was expanded.

Chandler and his editor, Williams, lured reporters away from the Wall Street Journal, the New York Daily News, the Washington Star, BusinessWeek and U.S. News & World Report.

In one of their biggest coups, they brought in Robert J. Donovan, the Washington Bureau chief of the New York Herald-Tribune and one of the most respected journalists in the country, to be chief of the expanded Times bureau in the capital.

And in January 1964, they hired a Pulitzer Prize-winning editorial cartoonist away from the Denver Post. As much as any other change at the paper, the arrival of Paul Conrad — brilliant, sharp-penned and liberal — served notice that an entirely new breed of Chandler was in charge.

Mouthpiece for GOP No More

To grasp the breadth of the changes, it is necessary to understand what The Times had been. More than merely a newspaper with a conservative editorial policy, it was an openly partisan mouthpiece for the conservative wing of the Republican Party.

Not only did it champion GOP candidates, its editors helped select them. Not only did it not, as a rule, endorse Democrats for elective office; it didn’t cover their campaigns. Readers could be excused for thinking that only one political party existed in Southern California.

Well before Chandler was named publisher, a poll of Washington correspondents conducted by writer Leo Rosten named The Times one of the three “least fair and reliable” newspapers in the country.

For most of the first 80 years of its existence, the paper was such a journalistic laughingstock that humorist S.J. Perelman once wrote that while traveling through the western United States by train, he asked a porter to bring him a newspaper and “unfortunately, the poor man, hard of hearing, brought me the Los Angeles Times.”

Chandler realized that to build up The Times’ reputation, he had to demand fair and nonpartisan news coverage. His efforts led him directly into confrontation with a powerful force for the status quo: his own family.

During Chandler’s first year as publisher, the paper ran one of the most important series in its history, stories that helped define the new Los Angeles Times.

The conservative movement that would lead to Barry Goldwater’s presidential candidacy in 1964 and to Ronald Reagan’s subsequent rise was in its nascence. On the fringes of that movement — and especially active in Southern California — was an ultra-right-wing organization known as the John Birch Society.

The Birchers argued that presidents Eisenhower, Truman and Franklin Roosevelt were either Communists or Communist dupes. They wanted to impeach Earl Warren, chief justice of the United States. They wanted the U.S. to withdraw from the United Nations. They saw the sinister hand of communism behind such government initiatives as fluoridation of the water supply and integration of the schools.

Alberta Chandler, the wife of Chandler’s uncle (and rival) Philip, was a prominent member of the Birch Society, and she and Philip had played host to Birch Society President Robert Welch.

But when Williams, the editor, suggested that the paper look into the organization anyway, both Otis and Norman Chandler gave him the go-ahead.

Reporter Gene Blake produced a five-part expose, written in calm, matter-of-fact language. The stories described the Birchers’ extremist tactics and positions and, largely through their own words, depicted them as a threat to, rather than a defender of, the American way of life.

After the series was published, Otis asked for an editorial criticizing the Birchers. When Williams showed him the piece, the publisher said it wasn’t tough enough. Williams wrote a new one, warning that the Birchers’ extremism and smear tactics were subversive acts that could “sow distrust and weaken the very strong case for conservatism.” Chandler signed it — and published it on Page 1.

The series and editorial landed like a bombshell. More than 15,000 readers canceled their subscriptions, and Chandler’s breach with some members of his family was widened still further. Philip Chandler resigned from the Times Mirror board seven months later.

But the series also served notice that The Times was in the process of becoming a different — and much better — newspaper.

George Cotliar, who joined the paper three years before Chandler became publisher and served as an editor for almost 40 years, said The Times had been widely regarded as “a crappy newspaper and a politically biased newspaper, and the Birch series and the editorial were a statement to the staff too.

“It was a sign that you now have a boss who believes in good, tough journalism, who wants to produce the best paper in the country and who’ll support you in your efforts and make it possible to achieve that,” he said.

That was far from the only example of Chandler’s reversal of long-held dogma at The Times. The 1962 gubernatorial campaign was another.

In 1958, the paper had covered the governor’s race between Republican William F. Knowland and Democrat Edmund G. “Pat” Brown in its traditional way: Brown’s campaign was virtually ignored while Knowland’s was championed.

In an extreme example of the paper’s penchant for treating Democrats like nonentities, one lengthy article featured Knowland’s attack on “my opponent,” “the Democratic candidate for governor,” who was described as a tool of “union bosses” and socialists. Not once did the article refer to Brown by name.

When, by late September, it appeared that Brown might win — as he ultimately did — Times political editor Kyle Palmer, the paper’s lead reporter on the campaign, wrote a column acknowledging that the situation “sounds a trifle grim for us Republicans.”

By 1962, Palmer was gone and the gubernatorial race between Brown and Richard Nixon was covered primarily by two new reporters: Richard Bergholz, who had come from the Mirror, and Carl Greenberg, from Hearst’s Los Angeles Examiner.

Of all the political figures to benefit from The Times’ partisanship over the years, none had been more favored, or more successful, than Nixon.

Since his first run for Congress in 1946, he had been championed by The Times as he successfully ran for U.S. Senate and then for the vice presidency on the Eisenhower ticket. He had the paper’s support when he ran unsuccessfully for president in 1960.

But by 1962, The Times had become a different institution.

Williams and Frank McCullough, one of the paper’s two managing editors, agreed at the outset of the gubernatorial campaign to monitor the coverage inch by inch to ensure that both candidates were covered fairly and equally. The paper warmly endorsed Nixon but also praised Brown’s accomplishments in the same editorial.

Nixon, by all accounts, was stunned by the turnabout. When he lost, he delivered a diatribe that would long haunt him, bitterly denouncing the press coverage — by which, it was widely realized, he meant The Times — and promising, “You won’t have Nixon to kick around anymore because, gentlemen, this is my last press conference.”

Years later, Otis Chandler would insist that the paper “wasn’t as bad as some people said when I took over. My dad had already started to make improvements.”

It’s true that in 1958 Norman Chandler had promoted Williams, a 27-year Times veteran, to the top editor’s job and had given him instructions to initiate a more aggressive and evenhanded approach to the news. But the newsroom was riddled with hacks, and Norman Chandler was unwilling to make sweeping personnel changes or to approve the expenditures necessary to effect significant improvement.

His son was perfectly willing, indeed eager, to do and spend whatever was necessary to achieve journalistic respectability. Otis and Williams — “perhaps the ablest newspaper editor of his generation,” in Halberstam’s words — became a formidable team.

A ‘Most Remarkable’ Revolution

Within four years, Time magazine and others were routinely mentioning The Times as one of the three or four best newspapers in the country.

In a cover story on Chandler in 1967, Newsweek said, “In the six years since his father made him publisher of The Times, Chandler has staged one of the most remarkable palace revolutions in U.S. journalism.

“To put together his galaxy of star reporters, Otis Chandler employed what in much of the newspaper business amounts to a secret weapon — money.”

The annual news department budget at The Times was $3.7.million when Chandler took over. His first year, he increased it 45%. By the time he left the publisher’s office, it had increased tenfold during his tenure.

“We’re going to spend as much money as it takes to be the best newspaper in the country and I mean, specifically, [better than] the New York Times,” Chandler said in remarks to the paper’s Washington Bureau in the mid-1960s.

The booming Southern California economy helped immeasurably, of course. So did the shutdown in January 1962 of the Mirror and the Examiner, the morning Hearst newspaper.

With the Mirror still losing money, it had been Chandler who wanted it closed, and his father had reluctantly concurred. When the Hearsts and Chandlers agreed to fold the two papers, The Times acquired a monopoly in the increasingly lucrative morning market, while Hearst’s Los Angeles Herald-Express (renamed the Herald Examiner) was left with a monopoly in the increasingly problematic afternoon market.

The agreement made sense financially for The Times, but it proved to be a boon in another way as well. Under Chandler’s direction, The Times scrambled to hire the best of the reporters and editors from the two defunct papers — and to get rid of its own deadwood.

Seldom has a newspaper had such an opportunity — to meld the best of three staffs. Thomas, who was among the editors brought over from the Mirror, said he believed that the windfall of local talent was as responsible for The Times’ subsequent success as the hiring of big guns from the East.

“You transformed the entire staff,” he said, “and the whole place had a totally different attitude.”

Within a few years, The Times had a 2-1 lead over the Herald Examiner in advertising revenue, which provides about 80% of the income for most newspapers. The Hearst paper was subsequently hit by a devastating strike and ceased publication in 1989.

Chandler was both more willing than most publishers to reinvest the paper’s rising profits in editorial improvements and more visionary in his approach to newspapering.

He foresaw the sprawling megalopolis that Los Angeles and its neighboring counties would become, and he wanted The Times to be the dominant paper “from Santa Barbara to the Mexican border.”

Toward that end, he initiated a more aggressive marketing program, expanded the paper’s geographic reach and started the Orange County edition to serve the burgeoning population there — the first such satellite plant for any metropolitan daily in the country.

Concerned by the growing competition from television, Chandler urged his editors to transform the paper into a regional daily newsmagazine that placed a high premium on analysis, interpretation and good writing — not just covering the day’s events but putting them in context and doing so in a lively and compelling fashion.

Ever concerned with the paper’s image and visibility nationally, he teamed with Philip Graham, then publisher of the Washington Post, to create the Los Angeles Times-Washington Post News Service to distribute the paper’s stories to client papers.

Unencumbered by union contracts, Chandler made major technological improvements at The Times, shifting from traditional “hot type” letterpress production to more flexible photo-composition and offset printing, and making The Times the first major newspaper in the United States to computerize typesetting.

At the same time, he shifted the paper’s editorial page philosophy from the extreme right to slightly left of center. His goal, he once quipped, was to make it a “militant middle-of-the-road paper.”

He moved gradually at first, then much more quickly, especially after hiring Day, who joined the paper as chief editorial writer in 1969 and later became editor of the editorial pages.

“Otis said he wanted a more assertive, more liberal editorial page,” Day said. “He wanted the paper to take what he called more ‘balls out’ positions, and he wanted us to change our position and editorialize against the war in Vietnam.”

Although Chandler had been opposed to Sen. Barry Goldwater in the 1964 presidential race, he had deferred to his father and reluctantly agreed to run an editorial before the Republican convention pledging The Times’ traditional support to whomever the party chose as its nominee — and that turned out to be Goldwater.

But in 1968, the paper endorsed Democrat Alan Cranston for U.S. Senate over Republican Max Rafferty, whom it called “an outspoken, militant conservative.”

Although The Times had, on rare occasion, endorsed conservative Democrats for state legislative and U.S. House seats, the backing of a Democrat for such a high office “was a momentous decision,” Chandler said in a 2005 interview.

After the paper’s decision to endorse Nixon for reelection as president in 1972 caused a newsroom firestorm, The Times announced in 1973 that it would no longer “routinely” endorse candidates for president, governor or U.S. senator.

Chandler said the move would help allay the concerns of readers who, mindful of the paper’s partisan history, “find it hard to believe that this newspaper’s editorial page endorsements really don’t affect the news columns.”

Nevertheless, the increasingly liberal stand on most major issues angered many in the Chandler family. Until shortly before his death in 1973, Chandler’s father had helped insulate him from those protests. But Otis had certainly been aware of the family pressure.

“They didn’t like the L.A. Times,” he said in the 2005 interview. “They resented my position at the L.A. Times and felt there were a lot of things I could have done differently.”

The shift on the editorial page came as the region itself, once dependably Republican, was becoming less conservative. Did The Times change out of foresight or luck? Or did it, in some way, lead the region into change? Chandler said there was no simple answer:

“The region was changing, the demographic was changing, the type of paper was changing,” he said. “There were so many changes going on, and I think if we hadn’t kept up with the flow, The Times wouldn’t have continued to do well financially I’m glad we did what we did.”

Chandler’s primary role was to provide the impetus, framework and financial support for change, rather than dictating specifics. But he did send memos to Williams, the editor, periodically in his early years as publisher — criticizing the business and sports sections, for example, and complaining about the content and design of the Sunday magazine, then as now called West.

Williams was 21 years older than Chandler and often pulled in his reins. Chandler later praised his editor for frequently “reminding a young publisher that you can’t change a whole paper overnight.”

By the time Thomas became editor in 1971, many of the major changes had been made, resistance had greatly diminished and Chandler was stepping back to take a broader view. Also, because Thomas was more aggressive than Williams, more likely to take the initiative and less likely to urge caution, Chandler adopted a largely hands-off approach.

“My style was to do the job and push the boundaries, and once Otis realized I knew what I was doing, he let me do it,” Thomas said.

Thomas was largely responsible for the great length and literary style of many Times stories — qualities for which the paper became both celebrated and criticized. Even Chandler said some of those long stories made the paper seem “gray, somewhat dull” at times.

“But he never interfered with an editorial decision,” Thomas said, “never tried to tell me how a story should be written or edited or played, or how a page should look.”

Missteps and Controversy

Chandler’s reign as publisher was not an uninterrupted, 20-year victory lap. Some critics felt that his zeal for national recognition led The Times to underemphasize local news, particularly about minority communities.

Chandler contributed to that perception in 1978, when he responded to a television interviewer’s questions about the paper’s coverage of black and Latino communities by saying it was difficult to get those groups to read The Times.

“It’s not their kind of newspaper,” he said. “It’s too big, it’s too stuffy. If you will, it’s too complicated.”

Chandler later insisted that he hadn’t meant to demean blacks and Latinos, but the remark haunted him — and the paper — for many years.

Critics also thought his position at the top of the city’s power structure prevented The Times from aggressively investigating that establishment. When The Times consistently provided editorial support for various downtown redevelopment projects, civic activists were quick to say the projects would enhance the value of the Chandler family’s real estate interests there.

Chandler always denied any conflict of interest, and he invariably emerged from these controversies with his reputation for personal integrity intact. But in 1972, he suffered his most damaging blow — and it was, to a significant extent, self-inflicted.

Jack Burke, Chandler’s close friend since their days together at Stanford, had assembled an exploratory oil-drilling company called GeoTek in the late 1960s and early ‘70s.

Chandler knew and trusted Burke. The two had hunted together, and Burke was the godfather of Chandler’s eldest daughter, Cathleen.

When Burke asked Chandler if he’d like to invest in his company — and introduce Burke to other potential investors among the publisher’s wealthy friends — Chandler was happy to comply.

According to official documents, he wrote and telephoned a number of such people, including Evelle Younger, the former state attorney general and Los Angeles County district attorney.

Many invested with Burke, who raised more than $30 million among 2,200 individuals over eight years. Chandler himself invested more than $200,000 of his personal funds. But he didn’t disclose to other investors that he received $109,000 in finder’s fees and $373,000 in promotional shares of GeoTek stock for his efforts. When Burke was accused of fraud, Chandler too became a target of civil legal proceedings.

In August 1972, the Wall Street Journal broke the story, which dragged on for several years before a federal court sentenced Burke to 30 months in prison. The Securities and Exchange Commission dropped all charges against Chandler in 1975, but the case cost him more than $1 million in legal fees, and it had a devastating emotional effect on him.

He had family money, but he had looked on GeoTek as another chance to prove he could succeed on his own, and he wound up embarrassed and forced by the exposure to return his stock and finder’s fees. For the first time in his life, he found his personal integrity seriously questioned.

“I was more upset with myself than with Jack Burke,” he said years later. “This was the only big investment I ever made, and I didn’t do any investigation of it beforehand. How could I have been so stupid? I apologized to my wife and my children and my mother and father and everyone on the board and all my department heads.”

The GeoTek affair also damaged Chandler physically. For all his seeming calm and control throughout his life, he had suffered from sporadic bouts of insomnia and intestinal pain — diagnosed as a spastic colon — ever since he became publisher. The GeoTek debacle helped greatly exacerbate the colon problem.

Chandler had his own ways of blowing off such stress — like getting behind the wheel of a turbocharged Porsche. Because he had five children and heavy corporate responsibilities, his wife tried to dissuade him from this favored leisure time activity.

But he persisted and in 1978 — at age 50, after years of what he called “Walter Mitty fantasies about becoming a race car driver” — finally got a chance to race professionally. He entered a six-hour endurance race in Watkins Glen, N.Y., teamed with John Thomas, his motorcycle buddy and Porsche mechanic, who had long raced cars himself.

For several years, the pair had enjoyed a Saturday ritual. They would race their cars down the Pasadena Freeway at 140 mph in the predawn hours en route to weightlifting sessions at the Times gym and double cheeseburgers at Tommy’s, just west of downtown. Periodically, Chandler rented the now-defunct Riverside Raceway for a day so he, Thomas and their friends could race their cars.

Watkins Glen was to be one of the most enjoyable experiences of Chandler’s life. He and Thomas finished sixth in a field of 72 cars — third in their class of 22 — a remarkable performance for a 50-year-old rookie driver. Chandler was elated; many who knew him well and saw him after that race said they had rarely seen him happier.

It was at Watkins Glen that Chandler got to know Bettina Whitaker, who was an executive at Shakey’s International, a sponsor of his Watkins Glen car. Not long after, he left his wife, and three years later — a year after he moved out of the Times publisher’s office — he and Whitaker, 12 years his junior, were married.

“It wasn’t meeting Bettina that did it, even though Missy thinks so,” Chandler said many years later, referring to Marilyn Chandler by her nickname. “Missy and I had had a good marriage, but we just weren’t getting along anymore in the last 10 years. I was 50, and I didn’t want to be unhappy for the rest of my life.”

People who knew the Chandlers well say Otis’ first wife was enormously competitive. She was athletic, she surfed, she hunted and she was “always vying for equal status — or greater status — than Otis,” said Howard Gilmore, one of Chandler’s longtime hunting companions.

Over time, Chandler and others said, that began to wear on him.

Like many women of her generation, Marilyn Chandler had long put her own career interests on hold to raise their children. But as the children grew up and she had more time available, she embarked on a career of her own — “she got women’s lib” is how Chandler put it — and that exacerbated tensions between them.

Despite the liberalization of The Times’ editorial page under Chandler, he remained moderate, even conservative, on many issues, feminism among them.

In some ways, he was typical of the macho male of his era. One had only to visit the men’s room in his car and wildlife museum — its walls covered with posters of scantily clad women draped over shiny sports cars — to realize that his ultra-masculinity wasn’t limited to guns, barbells, fast cars and motorcycles.

Chandler told his wife he wanted a divorce while the two were on vacation in Montana in 1978. Although the decision stunned her, friends said they had long seen the breakup coming.

Almost 20 years after their divorce, the happily remarried Marilyn Brant DeYoung said she didn’t think she’d been competitive with Chandler, “except on the tennis court, where I did get upset when he beat me.” She said they had “a wonderful marriage,” and he was “an involved father, especially when he was younger, before he was publisher.”

Their son Harry concurred, although he also agreed with his mother that most of the family’s leisure activities “revolved around what Dad wanted to do” — camping, water skiing, cliff-jumping, surfing.

By all accounts, the family enjoyed their outdoor experiences together, for Chandler focused on his children as intensely as he did on everything else that mattered in his life.

“When he was with you, he was really with you,” Harry said.

Many Chandler associates said his marriage’s breakup and the end of his publishership were inextricably intertwined.

“I think he saw leaving Missy as getting his freedom in one way,” said David Laventhol, publisher of The Times from 1989 to 1994. “If he hadn’t divorced Missy, I’m not sure he would’ve left the paper. He saw them both as restraints on his freedom. Otis is someone who’s very used to having his own way, and she impeded that.”

But William Thomas, who was Times editor when Chandler made his decision to step down as publisher, said he remembered sitting in a taxi with him in Madrid in 1975 — before he’d met Whitaker, when he was still married to Missy — and hearing Otis say he wanted to give up the publisher’s job in three to five years.

Itching for More Freedom

Chandler was growing weary, worn down by the rigors of work and the burdens of responsibility, dispirited by GeoTek and his failing marriage, “getting by mostly on nervous energy, with big circles under my eyes,” he later said. He was convinced that he had taken The Times about as far as he could, and he wanted more challenges — and more freedom.

Like his father before him, he thought he should concentrate on companywide responsibilities, by succeeding Franklin D. Murphy as chairman of the Times Mirror board. Murphy was scheduled to retire soon, and Otis was determined to give up the publisher’s job in 1980, when he would have been publisher for 20 years — “four years longer than my father,” he often pointed out to those disappointed by his departure.

Unlike his father, however, he had not insisted that his children follow him into leadership positions at The Times. Although all three of his sons worked at the paper for varying periods, none ascended into the top executive ranks.

Norman, the eldest, went through an executive training program and rose to be composing superintendent — a position overseeing much of the physical production of the paper — before leaving in 1989, when he was diagnosed with an inoperable brain tumor. He died in 2002.

The youngest son, Michael, also worked in the paper’s production departments, ultimately taking early retirement in a companywide buyout. He lived out one of his father’s fantasies when he became a professional race car driver, but nearly died in 1984 when his car slammed into a wall at the Indianapolis 500. He eventually recovered from serious head injuries.

“When I came,” recalled Day, the former editorial page editor, “I thought [Otis] was going to build a progressive newspaper dynasty like the Washington Post or the New York Times. And it became clear over the years that he did not have any such intention.

“He told me several times, and other people, that no Chandler would again be publisher of The Times,” he added, “and I thought that was a curious thing to say, especially since some of the Chandler children seemed perfectly suited to be publisher, at least as suited as Otis.”

In 1977, Chandler brought Tom Johnson, publisher of the Dallas Times-Herald and a former aide to President Johnson (no relation), to Los Angeles as president of The Times and heir apparent for publisher.

On March 5, 1980, Chandler announced that Johnson would become the fifth publisher of The Times — and the first since the paper’s infancy who was not a member of the Otis or Chandler families. Chandler would assume the newly created position of editor in chief of Times Mirror and, on Jan. 1, 1981, he would succeed Murphy as chairman.

Chandler insisted that he wasn’t giving up the journalistic chase or losing his competitive edge, simply assuming a larger corporate responsibility.

“Together,” he wrote to Johnson after the changing of the guard, “we are going to push the New York Times off its perch.”

But most of his friends and associates said he didn’t really have his heart in his new jobs. Both Thomas and Johnson said he hated being chairman. He missed the day-to-day challenge and the interaction with the editors and with the news.

“The corporate air was a little too rarified for him,” said Swayze, his secretary. “It wasn’t as much fun.”

In 1986, Chandler surrendered the titles of chairman and editor in chief, although he remained on the board and took on the largely ceremonial role of chairman of the company’s executive committee.

There was widespread speculation after he gave up his corporate titles that he had been gently nudged aside by long-disgruntled family members.

“It could be said that the anti-Otis crowd beat up on him so much that he just gave up,” said former editorial page editor Day.

But Thomas said “it really didn’t take much persuasion, because he really did want to go.”

Chandler himself said: “I think some of the family members and some of the corporate people were hoping I would step aside although I don’t recall that there was strong pressure.”

Heirs to other great newspaper dynasties have felt an obligation to remain deeply involved with their papers, virtually until their dying day, and Chandler’s decision not to do so remained a topic of curiosity among his peers long after he left.

Katharine Graham, who became publisher of the Washington Post three years after Chandler took over The Times, and who relied on him as a mentor in her first days on the job, said in a 1999 interview — the day after her 82nd birthday, when she was still very much involved with the Post — “I’m so committed to the company and so is ‘Punch’ [former New York Times Publisher Sulzberger] that I can’t imagine one of us actually leaving.

“I thought Otis was committed in the same way,” she said. “I never understood how he could just opt out like that.”

But Chandler, asked often about his decision to leave, said: “I gave 40 years of my life to The Times and Times Mirror. I decided it was time to be a little selfish, to give myself full time to the things I’d always enjoyed doing in bits and pieces.”

He may also have been frustrated by his inability to reach his stated goal of supplanting the New York Times as the most widely admired American newspaper. Asked in a 1997 television interview whether he was satisfied with his legacy, he replied: “I wanted to be No. 1. I wasn’t satisfied I’m that way whether I’m out riding my bike or racing a car.”

Even when he was publisher, Chandler wasn’t one of those workaholic bosses who could never let go.

He put in long hours, but he managed to have dinner with his family most nights, even if it meant doing more work at home after dinner.

He collected vintage cars and drove most of them to work at one time or another, alternating Porsches and Rolls-Royces with motorcycles, pickups and other vehicles in his growing inventory.

He worked out daily, lifting weights in a gym he had built at The Times and improvising when he was traveling. On one memorable occasion, a hotel maid walked in on him while he was doing full squats — with his wife on his shoulders in place of a barbell.

More than most high-level executives, Chandler also seemed willing to interrupt the workday occasionally when pleasure beckoned.

Thirty years later, he could still recall receiving a message from a fellow surfer one morning in the late 1960s telling him that waves were cresting at 12 to 15 feet off Dana Point — “the largest Southern California surf of my lifetime,” he said. “Within an hour, I had gathered things up in my briefcase, told my secretary, ‘Well, we can shine those afternoon meetings off,’ and headed for Dana Point..”

In a speech to a hunting conference in 1980, he described some of his other outdoor pursuits: “I am primarily a gun hunter, both rifle and shotgun. I occasionally hunt with a bow I am a saltwater fisherman and dry-fly freshwater fisherman, a gun collector, a sometime skeet and target shooter, an avid backpacker, outdoor photographer, trophy skinner, wild game gourmet but a lousy cook. The outdoors is my second home, my chapel, my retreat, my great love in life.”

Chandler — who learned to hunt when he was 10, shooting ducks with his father — began big-game hunting a year after he became publisher, and for most of the rest of his life, he tried to go on at least one major hunting trip a year, in Botswana, Mongolia, Afghanistan and Ethiopia, among other places.

“My trips gave me a balance, a perspective,” he said. “They also gave me quiet time so I could really think. It was the best down time I ever had, and I always kept a notebook with all the things I wanted to do when I got back.”

The Times, on his watch, consistently editorialized in favor of gun control, but Chandler himself was a strong advocate of the right to bear arms. In the 1980 speech, he complained that he felt increasingly like an outcast.

“I must confess,” he said, “I am getting darn tired of defending myself as a hunting person.”

Chandler said he wanted to hunt only “the rarest and the biggest and the best,” and he killed more than 100 such animals — 10-foot brown bears and polar bears, lions and musk ox, wild antelope and mountain sheep — many of which he had mounted on the walls of a trophy room in the home he shared with his first wife in San Marino.

Nearly a decade after his divorce, he installed the best of his animals in dioramas amid the classic cars and motorcycles in his Oxnard museum. Among them: the mate of the musk ox that nearly killed him in 1990.

The Wide-Open Road Not Taken

Many people wondered if, in retrospect, Chandler’s entire tenure at The Times had compromised his passion for freedom — if he would have been happier had he been outside all the time, surfing, hunting, riding and racing, instead of being stuffed into a suit, sitting behind a desk, making speeches and attending meetings.

“He said to me many times that he hadn’t wanted to come to the paper in the first place, but he felt an obligation to his family to do it,” said Robert F. Erburu, who succeeded Chandler as Times Mirror chairman. “He said he didn’t regret the 40 years he spent here. But he said he wished people realized that if he’d been left totally on his own, he might have done something different, so why did they question it when he finally decided he would do something different.”

Although Chandler often likened himself to the eagle that serves as the symbol of The Times — “I like to soar, to get above the minutiae and the crowds” — he insisted that as long as he was publisher, “I was living the life I wanted to live. Sure, like any business executive, there were times when I would like to have been away from it all, free of responsibilities. But there is nothing as fascinating as the newspaper business, and I can’t imagine any challenge more satisfying than the work we did to improve The Times.”

When Chandler left the publisher’s office and again when he left the chairman’s job, his former colleagues worried that without him, they would no longer be immune to corporate and outside pressures.

“With Otis gone, the heat shield was gone,” Johnson said.

Sure enough, both Thomas and Johnson said that after Chandler left, they were “pressured by the sixth floor,” where Times Mirror corporate offices were, to fire Day, whom Erburu and many in the family and on the board regarded as too liberal. Both refused. But in 1989, two months after Laventhol replaced Johnson as publisher, Day was removed.

In 1998, Chandler dissolved his last official ties with The Times. He was 70 then, mandatory retirement age for members of the board of directors. His two predecessors as chairman — his father and Murphy — had been invited to remain on the board, in a non-voting capacity, after their 70th birthdays, but Chandler was not extended a similar invitation, and he was clearly hurt by that.

“Would I have wanted to stay, given what was happening at The Times and Times Mirror?” Chandler asked a year after stepping down. “I don’t know but I didn’t have that choice.”

He remained an avid reader of the paper. “Nothing but my kids is more important to me than the Los Angeles Times,” he said in 1999.

But he also worried about his legacy, and he increasingly spoke critically, if only in private at first, about his unhappiness with the direction of Times Mirror and the paper under Mark Willes, a former executive at General Mills who had been hired to succeed Erburu as chairman and chief executive in 1995 and also assumed the title of Times publisher when Richard T. Schlosberg III retired unexpectedly in 1997.

Willes had taken charge of the company after a deep and prolonged recession that hit The Times particularly hard; circulation at the paper was declining, and both the stock price and the profits of Times Mirror were falling even faster. Numerous top Times reporters left the paper, many to join the New York Times or to pursue other interests.

Willes made several major cutbacks and refocused the company’s efforts on newspapers, saying Times Mirror should concentrate on the business it knew best. Wall Street responded favorably. The stock price tripled during his first three years at the company, and circulation grew modestly.

At a time when newspapers were becoming increasingly vulnerable to competition from the Internet, television, direct mail and other sources for information and advertising, Willes said it was imperative that they market themselves more aggressively and improve journalistically — to make themselves more relevant to readers and more valuable to advertisers.

Chandler acknowledged that it was a difficult time for newspapers, but he disagreed vigorously with Willes’ approach. Willes, he said in 1999, was “basically undoing what I and my father and Franklin Murphy all did, dating back to 1958. Going with newspapers only is a flawed strategy, a dangerous philosophy that puts The Times at risk.

“Newspapers are a mature, non-growth industry, vulnerable to cyclical economic downturns and increases in the cost of newsprint,” he said. “That’s why we diversified the company and went into television and cable and forest products and books and medical and legal publishing.”

During Willes’ brief tenure as publisher — he relinquished the job to Kathryn Downing in 1999 so he could concentrate his energies on Times Mirror — he did initiate a number of controversial strategies designed to increase Times circulation and advertising revenue. But results were slow in coming, and many top-level executives left.

The change that ignited the biggest debate was Willes’ announced intention to blow up, “with a bazooka, if necessary,” the “wall” that had traditionally separated and insulated the newsroom of the paper from the business department to avoid conflicts of interest.

Although Chandler worried that the paper’s standing among opinion-makers would decline and that the new management was no longer committed to making The Times the best newspaper in the country, he said others in the Chandler family didn’t share his concerns or his priorities.

Various Chandlers controlled about 65% of the Times Mirror voting stock before the sale to Tribune in 2000, and most of them “love Willes,” Otis said several months before those negotiations began. “Mark has the stock price and dividends up, and that’s all they care about.”

In a controversial 1996 story in Vanity Fair, Chandler was quoted as criticizing his relatives as “coupon clippers elitists bored with the problems of AIDS and the homeless and drive-by shootings.” They wished The Times wouldn’t cover those issues, and they weren’t interested in either the paper’s editorial quality or its social responsibility, he said.

That article deeply wounded some of the 160-odd descendants of Otis’ grandfather, family patriarch Harry Chandler. Many had led quietly productive lives outside the newspaper industry and had tried to keep their complaints about cousin Otis and The Times within the family circle. Chandler tried to make amends, claiming he had been misquoted, but the damage had been done.

Several prominent members of the family — cousins of Otis who reflect the more conservative side of the family — declined requests to be interviewed for this article.

Laventhol, Johnson and Thomas, among others, agreed that Chandler was just about the only member of his family who was interested in the social issues he mentioned in Vanity Fair, and they shared his anxiety about the threat he said the family’s indifference posed to his legacy and to The Times.

Despite Chandler’s worries and despite what he said was a “constant stream of calls and letters” from Times executives past and present, asking him to “do something” about the direction of the newspaper, he made no real effort for most of Willes’ tenure to influence what was happening at Times Mirror Square.

“That’s not in my nature,” he said. “I don’t butt in.”

Then came the Staples controversy.

A Newsroom Hero Again

In October 1999, The Times published a special issue of its Sunday magazine devoted entirely to Staples Center, the sports arena and entertainment venue then about to open in downtown Los Angeles.

Unbeknown to the reporters and editors who worked on that project — and to the entire editorial staff of The Times — the paper had agreed to share the profits from the issue with Staples Center as part of a complicated arrangement by which The Times became a “founding partner” of the arena.

This was a flagrant violation of the independence of the editorial department, and it placed the credibility of the paper in jeopardy. When stories in local alternative weeklies, followed by the New York Times and Wall Street Journal, disclosed details of the deal, the newsroom erupted in protest, circulating petitions and demanding an apology from Downing, the publisher, who had signed the original founding partner agreement.

Although Chandler had previously been insistent that his criticisms of the business strategies pursued by Times management remain private, this undermining of the paper’s editorial integrity stirred him to action. He wrote a statement, dictated it to Bill Boyarsky, then city editor, and asked that it be read aloud to the newsroom staff.

Word that Chandler was breaking his silence ricocheted through the newsroom. Three top editors asked Boyarsky not to read the statement aloud, fearing that it would further provoke an already enraged staff. The city editor, who had been hired during Chandler’s heyday as publisher, said he felt an obligation to carry out his former boss’ wishes.

“I said he was a great man who made this paper what it was,” Boyarsky would say later. “We wouldn’t be working here if it weren’t for him.”

The statement was a stinging and unprecedented rebuke of Willes and Downing.

“One cannot successfully run a great newspaper like the Los Angeles Times with executives in the top two positions, both of whom have no newspaper experience at any level,” Chandler said.

He accused Willes and Downing of misusing and abusing the newsroom staff, of “unbelievably stupid and unprofessional handling of the Staples special section” and of perpetrating a “scandal” and a “fiasco” that posed “the most serious single threat to the future survival and growth of this great newspaper during my more than 50 years of being associated with The Times.”

This was, he said, “probably the single most devastating period in the history of this great newspaper. If a newspaper, even a great newspaper like the Los Angeles Times, loses credibility with its community, with its readers, with its advertisers, with its shareholders, that is probably the most serious circumstance that I can possibly envision. Respect and credibility for a newspaper is irreplaceable.”

Chandler’s words hit like a bombshell, both in the Times newsroom and in the newspaper business nationwide.

Overnight, copies of an old photo of Chandler were pinned and taped by the dozens to pillars and walls and bulletin boards throughout the newsroom, where some still remain. His remarks were reported in publications from coast to coast. The New York Times even published an editorial under the headline “The Truth According to Otis Chandler.”

Some at the Los Angeles Times felt that Chandler’s sharp public criticism of management — and the widespread attention it received — played a role in several subsequent management decisions. Those included an increase in the amount of news the paper printed, the adoption of a new statement of principles and ethical guidelines, and the publication of an investigation into how and why the Staples deal had occurred.

Others argued that the negative attention that was focused on the paper, Willes and the rest of the Chandler family in the aftermath of Otis’ statement helped accelerate and crystallize the family’s desire to sell The Times.

But Tribune had long had Times Mirror in its corporate sights. Given the principal players on both sides, the deal, or one very much like it, was probably inevitable, with or without Otis and without or without Staples.

Ultimately, there was little that Chandler could — or would — do to influence the fate of The Times beyond this brief but dramatic entry into the fray.

Away from the paper, off the board, with most of his Times Mirror stock in trust, he no longer had the power — or the inclination — to do anything concrete, not even as a fourth third-generation newspapering Chandler.

“Otis has gone surfing, and he’s not coming back,” Noel Greenwood, then senior editor of The Times, said in 1991, almost four years before Willes took over and eight years before Staples erupted.

As it turned out, however, several members of the Chandler family had begun to share Otis’ disenchantment with Willes, especially the company’s “lack of diversification, interest in new media and long-term strategic plan,” as Chandler’s sister, Camilla Chandler Frost, put it the morning the sale to Tribune was announced.

Having been rebuffed by Willes in a spring 1999 inquiry about buying Times Mirror, Tribune executives went around him several months later and dealt directly with Chandler family members and their representatives. The negotiations were so secret that Willes said he didn’t know about them until less than two weeks before the deal was done, and Chandler said he didn’t learn of them until he began hearing rumors two days before the agreement was made.

Though Chandler said he was “naturally saddened that Times Mirror will cease to exist and saddened by the end of local ownership,” he had wondered aloud for at least five years whether Times Mirror could continue to thrive on its own in the turn-of-the-century mega-media merger environment.

“It may sound strange for a Chandler to say this,” he said in one such conversation, “but I don’t think my family and the other people running the company are looking ahead enough to the Internet and other new media. And sooner or later I’m afraid we’ll have to align ourselves with one of those companies to ensure the long-term survival of The Times.”

When Tribune turned out to be that company, Chandler said, “Of all the people, of all the media companies that Times Mirror could join, this is the most logical and probably the best company.”

Chandler welcomed Tribune in part because he admired its management and strategy and in part because he thought its diverse holdings — four newspapers, 22 television stations and an aggressive Internet presence — would help stabilize The Times’ financial position in the new century.

But it was clear that he had felt a growing personal animosity toward Willes, and he saw the takeover as a repudiation of Willes and a vindication of his own criticism.

Chandler had long felt that Willes hadn’t shown enough respect for him and what he had accomplished. He was particularly resentful of Willes’ frequent promise to “reinvent” the newspaper and Willes and Downing’s unwillingness to consult him. And he took special pleasure in telling friends and colleagues about the telephone call he received from John Madigan, then-chairman and chief executive of Tribune, at 7 a.m. the day the takeover was announced.

“He told me, ‘You created a great newspaper, Otis, and we’ll make you proud,’.” Chandler said. “That’s more than I ever heard from Mark Willes.”

Six weeks later, on the day that John Puerner of Tribune Co. took over as publisher of The Times, Chandler had dinner with Puerner and Jack Fuller, then-president of Tribune Publishing — at their invitation.

“They asked me a lot of questions and made me feel welcome again,” Chandler said a few days later. “For the first time in five years, I felt like I wasn’t a leper. I always had the feeling that I wasn’t welcome in the building when Mark was in charge — that maybe they’d have a guard try to throw me out if I tried to come in. But even though the paper and the company has been sold, it feels to me like I’m home again.”

Chandler continued to meet regularly with Puerner and John Carroll, who became editor of The Times shortly after the Tribune purchased the paper and remained in that position until last summer.

“We treated him as an insider and told him what was happening,” Carroll said. “It was clear to me that it meant a lot to him and that he didn’t want to feel shut out.”