When a group of women harassed a San Diego hot dog vendor in February last year, Edin Alex Enamorado did all the things that have made him feared, admired and reviled — often all at once.

He uploaded video of the altercation to his TikTok account showing the women grabbing food without permission and calling hotdoguero Andres Arguelles Alvarez a “loser.” Enamorado also posted what he claimed were the women’s social media handles, telling his hundreds of thousands of followers in a slow, whispered voice-over to “hold them accountable.”

Discover the changemakers who are shaping every cultural corner of Los Angeles. L.A. Influential brings you the moguls, politicians, artists and others telling the story of a city constantly in flux.

National headlines followed, then a rally for Arguelles with hundreds of people lining up to buy him out for the day.

But Enamorado made mistakes as well. He got the identities of some of the women wrong and blasted out the social media accounts of people unconnected to the incident. He also wrongly identified the group of women as being San Diego State students and mistakenly tied them to a sorority.

Instead of expressing remorse, Enamorado doubled down.

That’s how I found myself on a warm Wednesday evening in August outside a police officer’s two-story home in a quiet Rancho Cucamonga neighborhood watching Enamorado, who had a megaphone in one hand and a smartphone in the other.

He had gotten a tip that one of the women in the San Diego video was the daughter of Upland Police Officer Nick Peelman, who, with another officer, had shot an unarmed Latino man 10 times a decade earlier. San Bernardino County prosecutors cleared the officers because they believed the man, who survived, was carrying a gun, according to news reports.

“The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree,” Enamorado yelled into the megaphone to the 40 or so people who had heeded his call to action as he paced on the sidewalk in front of Peelman’s home, making sure not to touch the lawn or driveway. Wearing a hat that read “All of Us or None of Us,” he spoke fast and clipped, offering enough fire and brimstone against the Peelmans to fill a sermon.

He’s fueled by a simmering fury — at those who harass vendors, yes, but also at himself.

“What do we do when street vendors get attacked?” Enamorado asked the people before him and the thousands more who were watching on Instagram Live.

“Stand up, fight back!” the crowd shouted.

As Enamorado continued to rail against the Peelmans, the comments from followers on his Instagram account cascaded on top of each other like a stock ticker.

Gimme tres de al pastor and a side of IDGAF.

Keep up the work Alex.

SICK EM BIG DAWG.

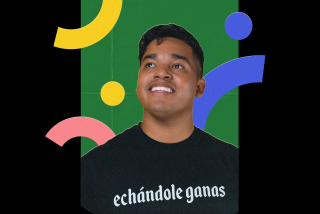

For the last 2½ years, the 36-year-old Cudahy native and son of Guatemalan immigrants has traveled from Las Vegas to the Bay Area and across Southern California on behalf of harassed street vendors — no incident too small, no tie too tenuous. His legion of supporters has cheered on as Enamorado has hounded offenders, then set up fundraisers to help the assaulted.

His intent is noble — but his tactics are often in-your-face and have sparked a debate among even his supporters about whether he crosses any lines, at a time when assaults against street vendors are more prominent than ever.

And Enamorado’s use of social media to shame people and his chaotic clashes with targets have also landed him squarely in the crosshairs of law enforcement.

Unlicensed food vendors began to set up on the streets of L.A. almost as soon as it incorporated as an American city in 1850. “Strangers coming to Los Angeles remark at the presence of so many outdoor restaurants,” this paper wrote in 1901, “and marvel at the system which permits men … to set up places of business in the public streets … competing with businessmen who pay high rents for rooms in which to serve the public with food.”

For just as long, thieves and code enforcement have targeted them.

Last year, cities across Southern California passed laws limiting where street sellers can operate or outlawed them altogether. Meanwhile, a string of more than 20 robberies of taco trucks and food vendors across L.A. last year — including six on the day Enamorado protested in Rancho Cucamonga — prompted the Los Angeles Police Department to assign detectives from its elite Robbery-Homicide Division to investigate the cases.

Decrying harassment, whether civic or criminal, against street vendors has become a cause célèbre, especially among younger Latinos, who organize fundraisers, flood city council chambers and share videos demanding justice.

“Nobody wants to see their mom and grandma harassed and maltratados [mistreated], and people want to see someone defending their people, right?” said USC Spanish professor Sarah Portnoy, who has written a book about food vendors in Los Angeles. “Young people are watching those videos all day long.”

Enamorado is by far the most famous of these self-appointed crusaders. He’s fueled by a simmering fury — at those who harass vendors, yes, but also at himself. He has spoken openly about his own run-ins with the law, and missed opportunities to stand up for the powerless. His actions and words have earned him a loyal following — and now, the full force of San Bernardino County law enforcement.

On Dec. 14, sheriff’s deputies arrested Enamorado; his fiance, Wendy Lujan; and six other individuals in connection with multiple felony charges that include conspiracy, kidnapping, assault and false imprisonment. On Sept. 3, prosecutors allege, Enamorado and others encircled a man in front of his Pomona home after the man had thrown a bottle at them. Later in the day, authorities say, the group beat up and pepper-sprayed a security guard at an El Super who had previously harassed a street vendor. A few weeks later, authorities allege, Enamorado and others assaulted another man in Victorville after he cussed them out for not clearing the way for his wife’s car during a protest against police brutality.

For 150 years, L.A.’s street vendors have had defenders, but never an avenger.

In June, six of the eight pleaded guilty or no contest to assault by means of force likely to produce great bodily injury. But Enamorado remains at High Desert Detention Center in Adelanto without bail on 12 felony charges and one misdemeanor. Activists are claiming political persecution against him and his fellow defendants, nicknamed the Justice 8.

After seeing what he and his followers brought to Peelman’s residence, it’s not surprising why law enforcement and polite society might want to shut down Enamorado for good.

Neighbors peeked from their living rooms or stood with their dogs at the corner. A piece of yellow caution tape hung from a nearby stop sign — a reminder of an attempt by Enamorado two weeks before to hold a similar protest, only for Rancho Cucamonga police officers to block access to Peelman’s street.

“Those days of [street vendors] being alone and attacked are over,” Enamorado announced through the megaphone. “This ain’t like the 1990s. This ain’t like the 2000s. This ain’t like the 2010s.”

Suddenly, he stepped away to take a FaceTime call.

It was Nick Peelman.

The two went at it a few weeks earlier at the Upland Police Department headquarters, with Enamorado calling Peelman a “bigot,” then releasing the confrontation on TikTok. This time, the 16-year veteran cussed out his antagonist and said that, while he didn’t condone what his daughter did to the hot dog vendor, Enamorado and others shouldn’t blame him for her deeds. Enamorado waved over some volunteers and gestured at them to start filming.

“You talk about freedom, but you want to infringe on our 1st Amendment right to protest?” he snapped. “This ain’t North Korea, motherf—.”

“You don’t know what to do in life, so you instigate s—. You’re a scared little boy, that’s all you are,” Peelman responded, before going on to call him a “fraud.”

The two jabbered back and forth for a few minutes. Afterward, Enamorado seemed dazed, remarking, “I thought it was my homie making a joke.” He took a swig of water, got back on Instagram Live, then returned to Peelman’s house and grabbed the megaphone again.

“Are we going anywhere?” Enamorado asked the crowd, which now numbered about 70. Cars cruised by, looking for a place to park.

“No!”

It’s easy to characterize Enamorado as an out-of-control bully. I sometimes winced at the videos he’s starred in, no matter how much the offender deserved a hectoring. I’ve worried that Enamorado’s yell-first-ask-later ways would lead to more legal problems — which they ultimately did.

But to dismiss Enamorado as a violent, attention-seeking criminal is to unfairly demonize him. Videos of teary-eyed street vendors grateful for his work, or of strangers who showed up en masse whenever he urged the public to support someone wronged, are all over social media and offer a different, more complicated narrative.

For 150 years, L.A.’s street vendors have had defenders, but never an avenger. To paraphrase the conclusion of the Batman film, “The Dark Knight,” he was the hero taqueros deserved — and the one they still need.