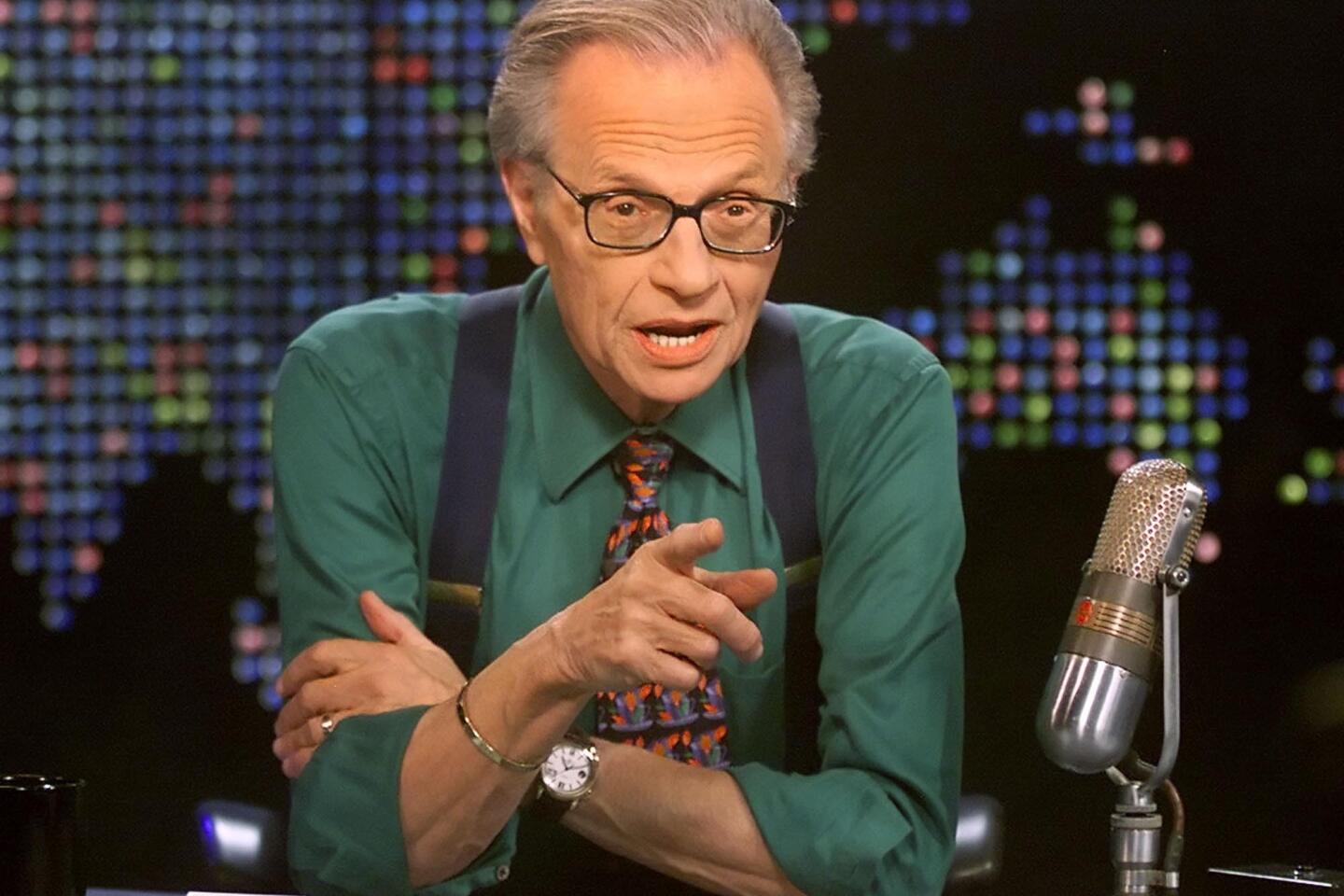

From the Archives: This Larry King is a man of the people talk-show host on throne No. 1

When the red “ON AIR” sign lit up across the room, Larry King cleared his baritone throat and spoke to America.

“Baseball’s back. Life’s OK,” King groused into the microphone.

Then he settled back in his chair. The black mufti of midnight hung over the Potomac, just outside his 12th-floor window. The Capitol building and the red eye atop the Washington Monument were the only brightly lit objects visible through the darkness. Everything else outside just twinkled, like the two dozen flashing buttons on King’s dirty beige telephone.

King waxed on a bit about his lust for baseball, for politics and for life in general. Then he punched up his first call.

“I just read your book,” said the voice from Grand Rapids, Mich.

“Already?” King asked incredulously. “It was just out yesterday.”

“No, no. The one you wrote back in ‘82,” said the caller.

“Terrific. So you gonna read the new one five years from now?” King asked with pleasant disgust. Then he hung up and took the next call.

At 54 and counting, Larry King is the most popular late-night talk show host in America.

Several million people listen to him each week on 322 radio stations, including KFI-AM (690) in Los Angeles. Another million or so watch his nightly interview program on Cable News Network. Each Friday he publishes a column in USA Today. His new book, “Tell It to the King” (G. P. Putnam’s: $16.95), hits the bookstores this week. The possibility of it becoming anything other than a best seller was ruled out months ago.

But Larry King also has heart disease and is just buying time. He’s been married three times (twice to the same woman), has two children (one adopted) and spends a lot of time at the races despite the fact that he is an admitted former track addict.

While he’s talking to callers from Poughkeepsie and Des Moines during his show, he’s also watching the day’s races on a soundless TV in the corner of the studio. It’s silent testimony to his flashdance thought process that he’s able to speak smoothly and coherently to Dave Winfield about his career batting average at the same time that he’s checking the tube to see if Juke Joke Johnny or Positively Poetic crossed the finish line first.

But Larry King doesn’t gamble-whether at the track or with his life-the way he once did.

“My last vice,” King joked, popping a red jelly bean in his mouth.

He only drinks three cups of coffee a day and he’s given up cigarettes and red meat. He walks 4 miles a day and works out at George Washington Medical Center three days a week.

He hasn’t given up women and the ponies completely, though. After all, he met his chief dating companion, Angie Dickinson, at Santa Anita. He closes each program on CNN with a signature sign-off directed at Angie: “1-4-3, Arrivederch’.” It is their personal shorthand for “I love you. See you later,” according to King.

But Dickinson is not his steady by any stretch of the imagination. King speaks as freely about sex as he does just about everything else in his life. Larry King is not shy. In fact, passion and impatience, not necessarily in that order, seem to rule everything else he does.

Once, he took porn star Marilyn Chambers up on her offer to demonstrate her best moves in the studio during a station break. He writes about it in the book:

“When the morning disc jockey came on, she (Chambers) was still naked. She started dancing around for him and then went over and danced right into his face. The poor guy didn’t know what to do. She said to me, `It’s like you taking your elbow, Larry, and rubbing it up against somebody.’

“Well, maybe not exactly.”

Four furrows etched King’s forehead. The rest of his face looked as if he had just eaten a lemon.

“There’s something about a book, you know?” he said. “Gives you a little rush! It’s not like a column. It’s got a heft to it, like it’ll really last. People don’t throw books away.”

King doesn’t write himself, though. His attention span is far too short. He simply tells his anecdotes of hobnobbing with the rich and famous to a tape recorder. Somebody else transcribes them and puts them into publishable shape.

“I don’t have the talent and I don’t have the discipline to write a book,” King said flatly.

In the case of “Tell It to the King,” SoHo Weekly editor Peter Occhiogrosso came up with the talent and discipline. He split the $60,000 advance from Putnam’s with King, but the bulk of the profits from the book will go into a newly created Larry King Cardiac Foundation.

“It’s going to help finance open heart surgery for people who fall between the cracks . . . Reagan’s people,” King said. “I mean, if you’re poverty stricken today you can get open heart surgery and, of course, if you have money you can get open heart surgery. But not if you’re anywhere in between.”

Heart surgery and the immortality that a book or a foundation can give him are topics very much at the top of King’s mind these days. He talks about them while he holds court after midnight five days each week in his dimly lit radio studio just outside Washington. The acoustic tile inside his office used to reek of the pack or two of cigarettes he consumed each day. It doesn’t anymore. He quit smoking right after his quintuple bypass operation last year. The desks used to be strewn with cigarette butts but nowadays they’re just loaded up with dozens of unread books.

“Philip Wylie said everybody wants immortality,” he said. “Why would you name a company Sanford and Son? To tell a human being about generations not yet born is laughable. It’s not interesting. Doesn’t mean a thing.”

King borrows ideas from others on a grand scale. His conversation is inevitably sprinkled with stories about, by or involving something he heard from somebody else. The best joke he knows about immortality, for example, belongs to Woody Allen:

“He said, `See this watch? On his deathbed, my grandfather sold me this watch.’ That’s Woody Allen’s commentary on immortality.

“I’ve never understood cheap people-people who want to take it with them. Hoarders, misers . . . I never understood that. It’s beyond me. Why would an 86-year-old man with $12 million want $12.1 million? It doesn’t make sense.”

King’s a millionaire who has to work, but he’s not rich.

“If you make a lot of money but you still got to get up in the morning and go somewhere, you’re not rich,” he said. “You’re rich when somebody else has to get up and go somewhere because you tell him to. That’s rich. I’m not rich.” He is compulsive, frenetic, restless.

Most of all, he’s maniacally interested in people. That, King maintains, is the secret of his success as a talk-show host.

Others say that he is successful because he has no fear of blurting out lines like, “Get to the point” or, “Now you’re making a speech. What are you trying to say?”

“I think he is brutally honest in a world where you have to cut through a lot . . . to find out what’s true,” said KFI General Manager Ken Kohl, where King’s program has been a late-night staple for more than two years. King’s taped Mutual show, which used to air here from 8 p.m. to midnight, was switched to a 10 p.m. to 5 a.m. weekday slot at the beginning of this week. The first four hours are live on tape, the next three are selections repeated from the previous night’s show.

Norm Pattiz, president of the Westwood One company which owns the Mutual Broadcasting System, speaks of King more as a fan than as his boss:

“There are very few radio stars who cross all demographic boundaries and Larry King is one of them,” Pattiz said. “He’s a radio guy who happens to be on television, not vice versa, and quite simply he’s the best interviewer I’ve ever heard.”

King’s stock-in-trade is book authors who put his TV and radio shows as the No. 1 stop on any promotion tour. He runs through the books that truly interest him after he has had the author on his shows, but rarely reads them beforehand.

“I don’t read the books I get. It’d ruin the interview,” he said.

The last time he read a book before the show was when he read Jimmy Breslin’s novel “Table Money.” When the New York newspaper columnist did come on the show, they talked about everything but the book.

“I’ve got to be curious about it and how am I going to be curious if I’ve read it?” he asked. “Supposing I started to ask things like: `In Chapter 3, where you have the character change . . . ‘ I mean, people listen and say, `What the heck does that mean? I don’t know Chapter 1 and 2 and here these two guys are having a conversation about Chapter 3!’

King hit the talk show circuit last week himself to promote his new book. First stop on the tour was the National Assn. of Broadcasters convention in Las Vegas where he interviewed the likes of Jerry Lewis and Rich Little for his own Mutual Broadcasting program while getting in a few plugs for “Tell It to the King” with some of his fellow talk-show hosts attending the convention.

This week, he found himself welcome at places like ABC’s “Good Morning America” and San Francisco’s KGO-AM where talk show host Ron Owens quizzed author King on Monday the way King usually quizzes others on his own radio and TV shows.

In Los Angeles, King is scheduled to hype his book over Tom Snyder’s “The Radio Show” Monday at 7 p.m. on KABC-AM (790).

But the preeminent talk-show host on Los Angeles radio, KABC’s Michael Jackson, declined to invite Larry King on his weekday morning program. A KABC spokeswoman said Jackson had only this to say about King:

“He’s successful is really what the quote would be. I mean . . . there’s really not that much to say. He’s good is what Michael says and that’s why he’s successful.”

KFI’s Kohl was a bit more eloquent: “He has an ability as an interviewer that is like an Everyman approach. If you had the opportunity to sit across from an author and ask him anything you wanted, what would you ask? Larry has the ability to know what most people would ask and that’s what he does.”

In 1982, King won a Peabody Award-one of broadcast journalism’s highest honors. But King is the first to protest that he is no journalist.

“I know I’m called a journalist and I’m highly complimented to be called it, but I don’t think of what I do when I go on the air as journalism,” he said. “I think of it as `infotainment.’ When I’m at a cocktail party and I run into Hedrick Smith or (Tom) Shales or (David) Brinkley, I know I’m not them. I definitely associate journalism with either the printed word or the side of television which is really the news.

“I think I’m the back page. I think I’m the fringe. I will ask things differently because I walk this area in between news and entertainment.”

The classic example of the difference between what King does and what a real journalist does came from Ted Koppel, according to King.

“I asked him how he’d cover a fire and Koppel said, `If there was a fire and you and I came running up to the fire and a fireman’s coming out, I would say, `What caused the fire?’ and you would say, `Why’d you want to be a fireman?’ ”

On the evening of the 20th anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, Larry King sat down around the kidney-shaped table where his guests sat waiting to discuss the martyred civil rights leader. With well-chosen words and careful phrasings, Rep. John Lewis (D-Ga.) and former Asst. U.S. Attorney Roger Wilkins waxed eloquent about the memory of King.

Off the air, during station breaks, the conversation turned to whether Yankee Winfield would be traded or how Kansas looked during the Final Four games of the NCAA basketball tournament. During a long stretch at the top of the hour when the newsbreak came up, King and his guests trashed Atty. Gen. Edward Meese as incompetent.

Back on the air, a caller from Minneapolis wanted to know if it was true that Martin Luther King Jr. was as formidable a philanderer as the Kennedys. Both Wilkins and Lewis-longtime associates of the civil rights leader-denied any knowledge of Martin Luther King Jr.’s extracurricular love life.

Larry King had heard differently, but only off microphone did he share the stories.

People who don’t want to talk about themselves are the toughest interviews, he said. Get them fired up with a few questions about what really excites them, and they take off like a Roman candle.

Even even a dull guest deserves some measure of courtesy, according to King. That’s why he is careful to avoid the prosecutorial stance of, say, a Mike Wallace or a Geraldo Rivera.

“I’m never rude to guests. I don’t think it’s right to be rude. I’m not a fan of rudeness. We invited them on the show. They’re a guest on my show. I’m there to learn as much as I can and to make it entertaining and informative as best I can.

“But now with callers I got a tough job and it’s solely up to me. There’s no handbook on judging calls. I can be rude. I’m not a rude person but I can be rude. Short.”

None of the calls that come into his 3-hour nightly radio show is screened. King does it himself, on the air. He compares himself to the editor of the letters-to-the-editor page.

“Except the editor gets 100 letters tomorrow, decides which 8 he’s going to print, discards 92 and edits 6 of those 8 for brevity or whatever, for one reason: to get me to read the page and to say, `Here’s what’s interesting today and I think you’re going to find these letters interesting.’

“I’ve got the exact same job. I’m the letters-to-the-editor guy except every letter gets on the air. We don’t screen calls. You get on.

“You never hear the caller say `good night.’ I don’t think I’ve ever heard a caller say `Good night, Larry.’ ”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.