L.A. says it can’t take care of its sickest and most vulnerable. The county isn’t buying it

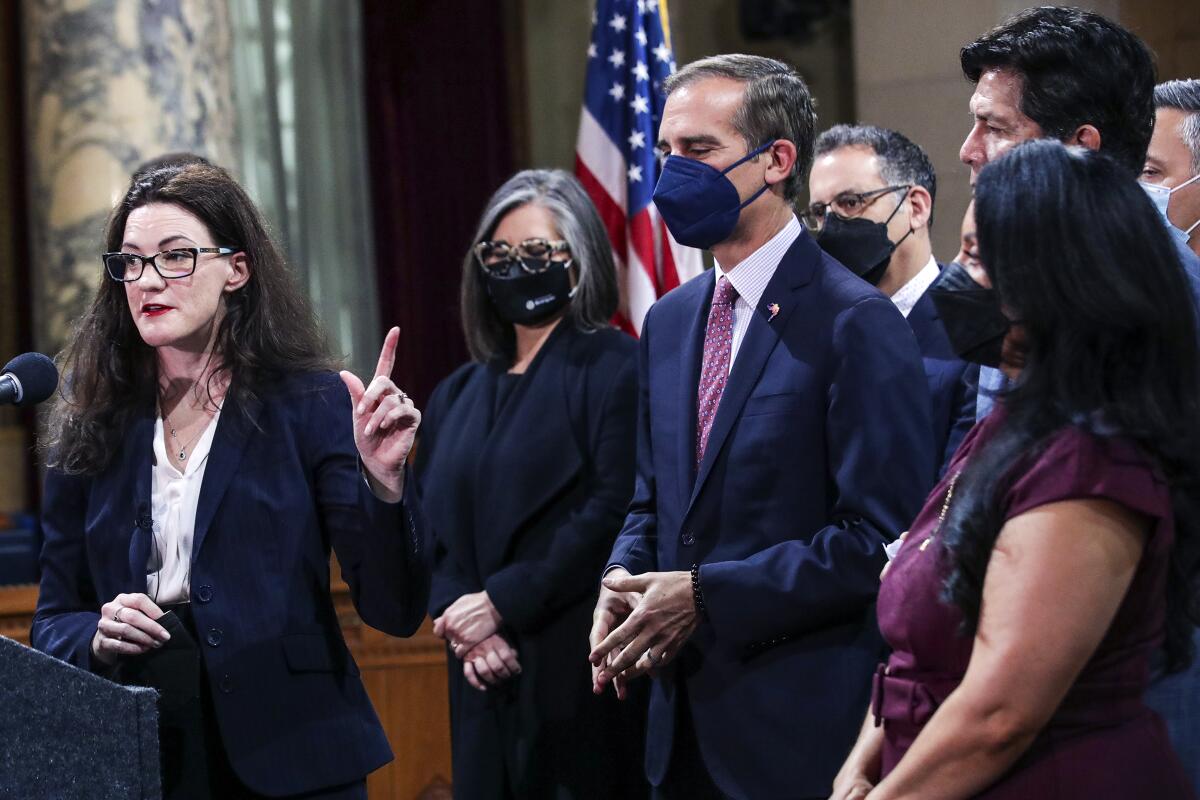

Earlier this month, with much fanfare, Los Angeles officials announced a partial settlement of a 2-year-old federal lawsuit over homelessness.

The city pledged to create housing, either permanent or interim, for 60% of the city’s unsheltered homeless population. Lawyers representing L.A. Alliance for Human Rights, the group that filed the lawsuit, endorsed the agreement.

Conspicuously absent from the event were representatives of Los Angeles County, which is also being sued by the group.

They bashed the settlement, saying the city was effectively seeking to dump responsibility for thousands of severely ill homeless people onto the county, promising no new housing that isn’t already committed and shirking responsibility for the people who most urgently need help.

City officials said the deal clearly lays out what the city can and cannot do. It also sets goals to make sure the city continues to grow the amount of both permanent and interim housing for homeless people, officials said.

The dispute has exposed a growing wedge between the city and county that threatens to undo years of cooperation between the massive bureaucracies at a time when homelessness continues to spiral out of control.

“I have a legitimate concern that in order for us to make significant progress, there has to be cooperation between the city and county,” said John Maceri, chief executive of the People Concern, a nonprofit focused on homelessness.

Housing is largely the city’s purview, while services are the county’s, Maceri said, adding, “If we cannot bring those two things together in a meaningful strategic way, we’re never going to have the kind of impact we need.”

The tentative deal, which the City Council and the federal judge handling the case must approve, would require the city to open enough beds over the next five years to accommodate 60% of the unsheltered population in each council district. The precise total is tied to the results of 2022 homeless count, which will be released later this year.

Based on the results of the last count in 2020, city officials estimate they would need to have at least 14,000 new beds to meet the 60% target. They believe these beds will give them the ability to enforce anti-camping measures more broadly once offers of shelter have been made.

The settlement is aimed at ending a long-standing legal battle around homelessness in the city of Los Angeles.

That target, however, includes only people “who can reasonably be assisted by the city, meaning they do not have a serious mental illness, and are not chronically homeless [or] have a substance use disorder or chronic physical illness or disability requiring the need for professional medical care and support,” the agreement says.

The document does not give an estimate of how many would fit that definition, nor does it spell out specifically the criteria for placing someone in that group, or who would decide what those criteria will be.

But a Times analysis, applying the language of the agreement to 2020 homeless data, found that the shift to county responsibility could involve between 5,000 and 6,000 severely impaired homeless people, or one in five living on city streets. That number could rise if this year’s count shows an increase.

The county could still find its way back to the negotiating table and, in advance of the announcement of this deal did make an offer of new resources.

Still, the current rift marks a move away from the cooperation displayed five years ago, when both city and county voters had approved ballot measures to provide billions of dollars in housing and services, with the city building housing and the county funding counseling services to accompany that housing.

In the late-1980s and early1990s, a court fight between the two governments led to the the formation of the joint city-county Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority.

“It seems like people have forgotten our history. It seems like we are going backwards to that place,” Maceri said.

Attorney Shayla Myers of the Legal Aid Foundation of Los Angeles, who represents Los Angeles Community Action Network, a party in the lawsuit, said this case has long been about finding ways to sweep homeless people off the street and out of sight. The dynamics in court , she said, meant the tensions between the city and county increased as well.

“The result of this litigation is to pit the city and the county against each other,” she said.

The current fight is over who can care for the region’s sickest and most vulnerable. The prevailing practice in recent years has been to rank homeless people based on the severity of their condition — an “acuity” rating — and reserve limited housing for those considered to have the highest need.

Now the city is saying that its shelter and permanent housing is not appropriate for those with severe physical or mental impairments and that they should be placed in specialized county facilities.

“We do not run hospital beds. We’re not clinicians. We’re not social workers. The type of housing that individual would need is the responsibility of the county,” City Council President Nury Martinez said earlier this month.

The settlement document said “qualified outreach or clinical staff” would decide which homeless people were suitable for city services but provided no specific criteria, setting off alarms for lawyers representing the county and agencies that provide outreach.

Heidi Marston, executive director of the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, said she’d be uncomfortable with front-line workers from her agency making determinations about people’s acuity.

Maceri, whose People Concern nonprofit uses county funds to hire teams of outreach workers, said there are insufficient resources for people in the throes of mental health crises or substance use disorder.

“I don’t know what the city’s definition is of those types of folks. The city doesn’t have the mental health expertise or the clinical expertise. The county has that,” Marston said. “So I think we need to look to the folks who are already working with the population and who have the funding and the charge to do the work to help us solve that.”

A Times review of documents that were part of settlement negotiations shows that the county had proposed spending an additional $154 million over the next few years on housing and services for homeless people on skid row. County lawyers, for months, have been arguing in court that this case is fundamentally about skid row and that the county shouldn’t even be part of it.

The proposal the county made would have included funds to vastly increase the size of outreach teams from the Department of Mental Health as well as nonprofit service providers receiving county funds, which is something the city has asked for.

Under this scenario, the city would have been required to spend an additional $80 million on various parts of the homelessness response. But two sources with knowledge of the negotiations said that city and alliance lawyers rejected the idea.

Daniel Conway, policy advisor for the group that filed the lawsuit, declined to weigh in on the specifics of the negotiations but said that the county’s assertions and attempts to make this case exclusively about skid row and not homelessness across the city and county were a “nonstarter” and that the county needed to be doing more to help people living on the streets.

The city acknowledged that about 13,300 beds are already being planned, including permanent supportive housing through Proposition HHH, as well as beds that people can stay in temporarily. City officials were unable to break down what proportion of these beds would be interim or permanent.

“There’s little to no value added by virtue of this agreement. They are simply recommitting to what they had already committed to and relabeling existing programs as a ‘settlement,’” said Skip Miller, partner at the Miller Barondess law firm and outside counsel for L.A. County in the alliance lawsuit. “Even worse, the settlement would exclude homeless people who are most in need — those who are mentally ill, have substance abuse or other issues, those who really need the help.”

In a statement, Jose Ramirez, deputy mayor for homelessness, declined to weigh in on the specifics of what the county proposed but defended the agreement, saying it “guarantees that we will add new permanent and interim housing solutions on top of our previous commitments, and any suggestion otherwise is untrue and disingenuous.”

Get the lowdown on L.A. politics

Sign up for our L.A. City Hall newsletter to get weekly insights, scoops and analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

“The city has worked tirelessly to secure an agreement that brings forward the addiction and mental health services that are in the hands of the county, because they’re not only critical to reaching a settlement — they’re urgently needed to save lives,” he said.

Holly Mitchell, chair of the county Board of Supervisors, said she was concerned by the details of the city’s deal with the plaintiffs but said she remains hopeful that the county can reach its own agreement.

“I trust that it is possible to come to a consensus that distributes resources equitably, doesn’t criminalize poverty, and meets the urgent needs of the homeless population during this crisis,” Mitchell said in a statement.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.