Newsom, in recall fight, says it’s ‘not acceptable’ for homeless to camp on streets

STOCKTON — Gov. Gavin Newsom expressed strong support Thursday for increased efforts around California to remove large homeless encampments, calling them unacceptable and saying the state will need more federal help to create additional housing and expand services for homeless people.

Newsom’s comments come at a time of growing alarm over the homelessness crisis, which has become a focus of criticism by Republican candidates running to replace him in the upcoming recall election.

Newsom took on the state’s most vexing and politically potent issue when he became governor, pouring billions into building more shelters and housing. The latest state budget commits $12 billion over the next two years to not just more motel purchases and funding for mental health care facilities but also encampment cleanups and hazardous waste removal.

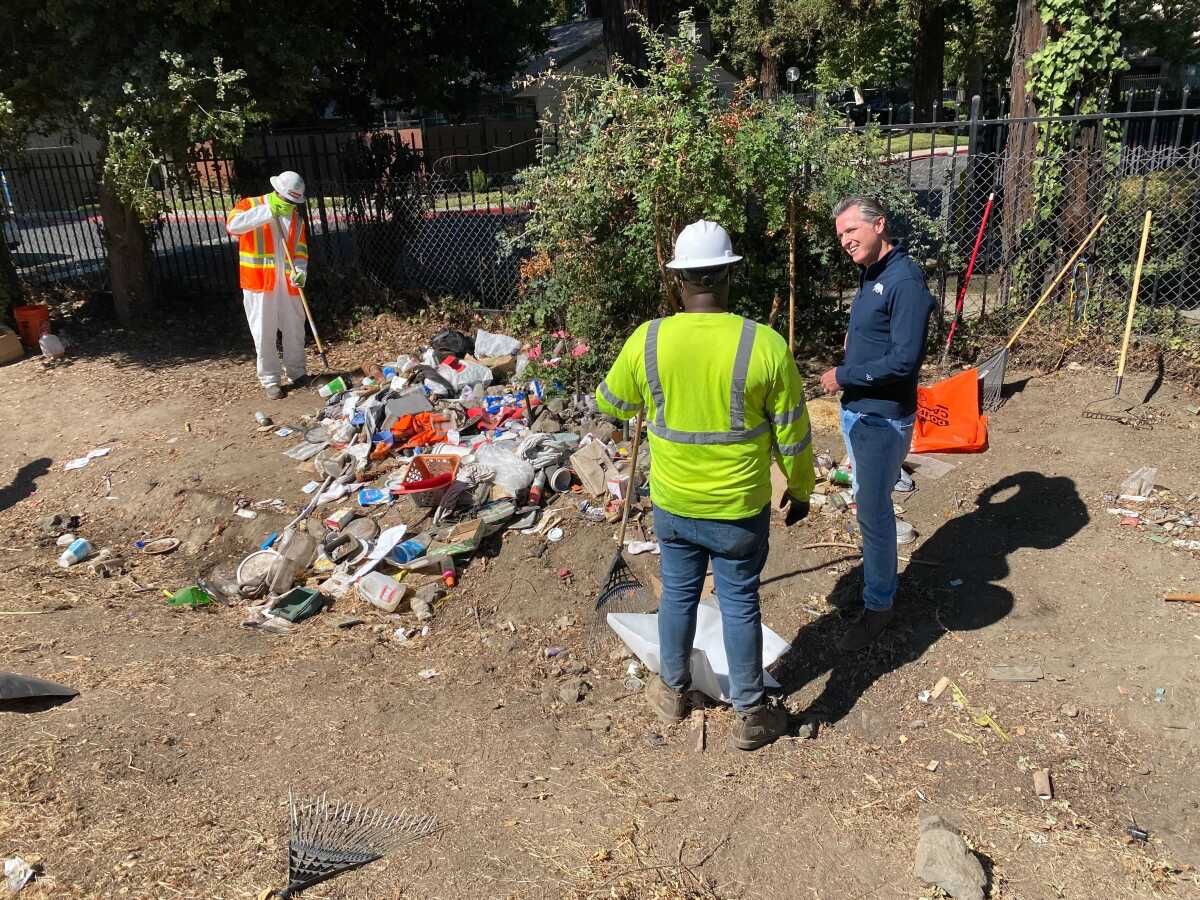

But the governor, in an interview Thursday with The Times as he watched state workers clear a homeless encampment here, made clear that tents along freeways and in public parks are not OK and that California needs to develop humane processes for moving people and clearing camps while also creating more housing options.

Newsom applauded the removal of homeless camps from Echo Park Lake and Venice Beach in Los Angeles, staking out a position that reflects a change in the public political dialogue about homelessness in California.

“You got to be honest, this is not acceptable,” Newsom said, staring at Caltrans workers cleaning up the remnants of a couple’s shelter on an embankment wedged between Interstate 5 and a housing complex. “People shouldn’t be living out in the streets and sidewalks … and the notion that until everything is perfect, we can’t do anything [about encampments], I completely reject. I also think it lacks compassion, because so many people’s lives have been changed, despite their obstinance in opposition to these things; it forces a different pathway in decision making.”

And yet he acknowledged what most Californians know: It’s not enough. The crisis has grown, more people are on the streets, and voters — who will decide Sept. 14 whether to recall and replace Newsom — are angrier than ever. One recent poll showed strong dissatisfaction with his handling of the issue.

“We’re going to need the federal government’s help at a massive level,” Newsom said on the Thursday morning trip to Stockton, which has seen homelessness grow to nearly 1,000 unhoused residents in recent years. “We’re talking to the feds about it now. We need a massive intervention of support to get under the hood here and turn this around.”

Newsom said he’s been focused on cleaner streets since his days as a county supervisor and later mayor of San Francisco. Still, his focus on how encampments affect surrounding businesses and residents is notable. Newsom has been crisscrossing the state in recent months as the recall campaign took shape, talking about a need to beautify the state.

It’s a recognition that voters want to hear that their government is not only helping people in dire straits but also striving to make the state cleaner and safer.

Police, outreach workers roust homeless campers in the middle of the night along the boardwalk, which has become a focal point in the L.A. homeless crisis.

That can be complicated when it runs up against homeless people who have been on the street for years and with intricate physical and psychological needs as a result of the trauma they’ve experienced.

Among them are James and Debra Scovone, who sat on egg crates eating Krispy Kreme doughnuts as California Department of Transportation workers, laboring under the governor’s gaze, lugged several white jugs the couple had planned to transform into a water heater and threw them in a dumpster.

James had been gathering the supplies for months, hoping to add some permanency to their tarp-covered structure at the bottom of an embankment, which was off the beaten path and hidden from public view.

The Scovones have been homeless on and off for 13 years. They explained to Newsom how three days wasn’t enough time to collect their possessions and organize their lives before being asked to leave. They also described how the interim shelter options don’t allow for couples to stay together. They’d rather live on the streets and panhandle as they put the pieces together to find a permanent place to stay.

Debra scratched a scaly left hand caused by psoriasis. She said the outreach and medical workers who flanked Newsom had been a help, but she and her husband couldn’t find stability when Caltrans workers or police told them they needed to move every few months.

“What you describe is that perverse dilemma,” Newsom said to the couple. “You need that stability in order to then figure all the rest out. We’re demanding you figure the rest out before you get the stability. It doesn’t make any damn sense.”

Newsom wished them luck — encouraged by John’s insistence that he and his wife were lining up a permanent place to stay with the help of outreach workers and some local members of the Hells Angels.

When San Francisco’s homelessness problem swelled in the early 2000s, Gavin Newsom endorsed a radical plan for the famously liberal city.

For a man who walked the Tenderloin in San Francisco as a local elected official, the scene at this cleanup — one of 22 happening on Caltrans land across the state this week — symbolized the challenge Newsom and local officials face when the needs of people living on the streets cross with housed voters’ anger over tent cities and mounds of trash along their streets.

Newsom has made homelessness the centerpiece of his work since he was elected governor in 2018. Each year at the behest of municipalities, he poured hundreds of millions of dollars into building more shelters and navigation centers. The flood of pandemic stimulus dollars presented a new opportunity to change the paradigm as well.

The state assisted local governments in purchasing hotel rooms and apartments for 6,000 people at a cost of nearly $750 million — the largest expansion of shelter and housing for homeless people in the the state’s history.

When asked by The Times how Californians should measure success, Newsom was reluctant to offer a specific number for how much he’d like to see homelessness drop. Instead he framed the issue around what citizens experience on their drives to work and walks in parks.

“People need to see and feel that not only we have a plan, and we have a strategy, but we’re holding ourselves to a higher level of accountability, and we’re performing” Newsom said.

“We’ve got tools and resources. Now [voters] want to see results. So finally there was progress in Venice Beach. Finally there was progress in Echo Park, but there are hundreds of other examples,” he said later.

He described driving by large encampments in Echo Park and Venice Beach and thinking to himself, “This is unacceptable.”

Both encampments were cleared by authorities, although the Los Angeles Police Department and other officials came under fire for the secrecy of the operation and the force used, at times violently, to remove protesters who had gathered in Echo Park. Months later, the city moved much more slowly, if more gently, to relocate homeless people who had bedded down on the Venice boardwalk — and that too drew criticism.

At the Scovones’ spot, a nestle of brush littered with trash and bikes and their personal possessions, Caltrans workers had posted a sign 72 hours in advance telling them they’d have to move. Outreach workers and medical and psychological professionals who had known them nearly a decade checked in to see whether they’d be interested in a shelter.

The Scovones piled carts and said they’d move on and find a place to bed down a mile away. While sympathetic to their reality, Newsom rejected the notion that people were “service-resistant” and also that it was acceptable for people to stay in situations like this — where tents hug freeways and a fire could start at a moment’s notice on the sloping embankment, which is covered in knee-high grass.

Newsom asked outreach worker Dennis Buettner, who works for San Joaquin County Behavioral Health Services, whether there were any private rooms where a couple like the Scovones could stay. Buettner explained that a local hotel had participated in a homeless sheltering program during the pandemic but had jumped at the chance to return to regular operations.

When Buettner mentioned that another hotel had recently been purchased through Project Homekey, Newsom’s face lighted up. The state program’s success is something the governor returns to constantly. His new budget includes billions more for hotel purchases and money for local governments to spend as they see fit.

That money has been a godsend for local officials such as Sacramento Mayor Darrell Steinberg, who has made homelessness one of his highest priorities. In a telephone interview, Steinberg said no governor in his time in California politics has been as focused on homelessness as Newsom. Steinberg described how $100 million from the state and federal government has flowed to the state’s capital, which made possible a master siting plan for a slew of new interim and permanent housing construction, which could end up getting about 9,000 people off the streets.

Steinberg’s focus has and continues to be finding permanent solutions to homelessness, but he too has noticed a shift in the way homelessness is being discussed in California among politicians.

“When you see people out on the street, it strikes at the heart and at the conscience,” Steinberg said. “People should not be living in that way. It has an impact on our businesses and our neighborhoods, and we must lead with a big heart. That’s not inconsistent with saying our communities should be cleaner and safer.”

State Sen. Susan Talamantes Eggman (D-Stockton) said the misconception about homelessness is that it’s found only in California’s metropolises. She said there’s a profound need for mental health beds and more wraparound services here, yet her constituents see the billions that have been spent and wonder why more is required to help California climb out of the crisis.

“People say to me, ‘We keep passing things, but I still see this everywhere,’” she said.

Newsom said he recognized this frustration and feels it himself. Without naming specific locations, he said that counties and cities need to do more with the dollars they’ve received. He spoke at length about how more dollars will go to places that show results.

“I’d be candid with you,” he said. “The resources we provided the cities in the last couple years, I haven’t seen the commensurate results.”

“I think people have been too passive at the local level. I don’t think it. I know it. I mean, look around,” Newsom said later in the interview.

Newsom’s staff kept him from putting on gloves and joining the cleanup workers as they picked up garbage. It included hazardous material, they said. The Scovones were gone — off to rebuild — and another encampment cleanup awaited the crew once it finished.

Newsom stared at the pile of trash, insisting that he wanted to help with the cleanup. The Caltrans workers laughed.

They smiled and took photos with the governor before he headed off to Southern California and another highway cleanup.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.