The remote work revolution is transforming, and unsettling, resort areas like Lake Tahoe

TRUCKEE, Calif. — For years, Ben Jarso couldn’t mix work and play. He worked at Facebook in Silicon Valley and on weekends drove almost four hours to Lake Tahoe to hit the ski slopes. When pandemic-related restrictions freed him to work remotely, he decided to merge his passions.

Truckee, a town on the lake’s north shore, was a perfect choice with Wi-Fi-ready houses and easy access to his favorite ski resort. He started making offers on properties. Again and again he lost out. Turns out too many other people had the same idea.

He finally got a house, but it took quick action. He contacted the seller as soon as the four-bedroom home popped up on his real estate app, made the first offer and agreed to no inspection requirements. His new $900,000 home has a large pine deck and two fireplaces and boasts views of Donner Lake.

“I think it was a steal,” said Jarso, a 31-year-old product manager.

The Lake Tahoe property boom is a vivid example of a trend that emerged last spring when white-collar workers got the mandate to start working remotely. Those with the money and newfound freedom to work from anywhere have headed to the mountain, beach and desert wonderlands where they used to only be able to spend their weekends.

Housing markets are hot nationwide, but few areas have seen the surge in home prices and residents as outdoor vacation destinations.

“You can live your life on vacation,” said Rich La Rue, a real estate broker in the Palm Springs area. “All the things that you love to do: hiking, biking, whatever it is. A property comes on the market here and it’s a feeding frenzy.”

Case in point: the average asking price of a home in the desert city is now $1 million, a 30% one-year increase.

It’s not just California. Areas with easy access to the outdoors have seen overwhelming demand — and rising housing costs — over the last year. Median rents in Boise, Idaho, are up 23%, the nation’s highest jump. In Bend, Ore., where locals boast that you can see no fewer than three mountain peaks from town, the average home now lasts on the market for only three days. East Coast destinations such as Cape Cod, Mass. and Palm Beach, Fla., have seen a surge in buyers from Boston and New York City.

Real estate firm Redfin recently found that the demand for second homes across the country nearly quadrupled that of primary homes during the pandemic, and that the average sales prices for homes in towns known for seasonal living far exceeded price hikes in other areas.

In Truckee, the deluge of remote workers is hard to miss in the town of 16,000. Along the blocks of quaint art galleries and clothing boutiques in the center of town, a Realtor’s storefront window advertisement highlights the real estate boom: Homes in some neighborhoods have spiked 146% and are selling 63% faster than last year. Locals complain about increased traffic on the streets — and the ski slopes.

Overall, Truckee’s median home price has nearly doubled to $2 million over the last year, and the number of available homes has dropped almost 80% over the same time, leaving just a couple dozen for sale, said Mike Simonsen, chief executive of real estate analytics firm Altos Research.

Truckee’s home-buying spree also has been fueled by historically low mortgage interest rates during the pandemic, which has allowed people to add another home without needing to sell their first. The ability to work from anywhere has blurred the traditional line between main and vacation houses, Simonsen said, with analysts dubbing the trend, “co-primary homes.”

Simonsen should know. His family bought a home in Truckee in 2015 and they’ve evenly split time during the pandemic between that property and their San Francisco house.

“We’ve had more contact with our San Francisco friends in Truckee than we ever had in the city,” he said. “It was surprising how many people were here.”

Data bear that out. Truckee saw the largest percentage increase in families relocating from San Francisco during the height of the pandemic of anywhere in the country, according to a San Francisco Chronicle analysis of U.S. Postal Service change-of-address data. Rather than grinding out Friday night traffic from San Francisco to Truckee, newly arrived tech workers now boast about skiing and mountain biking all week and then reverse commuting to the city for a fancy weekend dinner.

For Jarso, who lived in a one-bedroom apartment in San Francisco’s tony Pacific Heights neighborhood before moving, the draw wasn’t only the pull of the mountains, but a push away from the city. Over the last year, both his car and his girlfriend’s were broken into. And all the entertainment, restaurants and cultural attractions that make San Francisco vibrant aren’t available.

“Part of the lure of living in the city is this grand bargain,” Jarso said. “You’re going to pay this exorbitant rent, but you’re going to have proximity to all these things. When those things aren’t around anymore, the quid pro quo doesn’t make sense.”

Even more of an incentive was the price. Despite the run-up in costs, he was able to get a much bigger house for his money in Truckee than he could across much of the Bay Area.

The same mix of urban fatigue, lower costs and the draw of more space — both indoor and out — led Catherine Joubert and her partner to leave their cramped apartment in Hollywood and buy a home in La Quinta, a Coachella Valley resort community near Palm Springs, last summer.

The couple already knew the area because they’re devotees of the Coachella music festival. Last spring, Joubert lost all her work as personal stylist and her partner’s media production company began working remotely. At first, they planned to rent a place around Coachella for just a month but quickly decided they wanted to buy, in part because of the six parrots they keep as pets.

Before the pandemic, squeezing everyone into an 800-square-foot apartment was doable. But when the pair started taking work calls at home, Joubert said, the parrots began squawking uncontrollably and the noise became inescapable.

“They take up a lot of space with their big cages,” Joubert said.

The solution was a $330,000 three-bedroom home that they upgraded with a new pool and spa. Now, they have enough space for an office plus an entire room for their parrots.

“When we need our crazy city fix, we just drive to L.A.,” Joubert said. “Then we get the hell out.”

Homebuying among out-of-towners is so strong — Joubert has new neighbors who moved in from New York and the Bay Area — that the couple’s house was recently appraised for $100,000 more than what they paid less than a year ago. But they’re staying even after the pandemic subsides. Her partner has secured the ability to work from home indefinitely. And Joubert is planning to become a Realtor in the area.

Back in Truckee, community members are grappling with the newcomers. Truckee faced a shortage of available homes for teachers, nurses, public safety and service workers even before the pandemic. Elected officials have worked for years to speed the building of apartments for low- and moderate-income families all across town, many of which are now under construction.

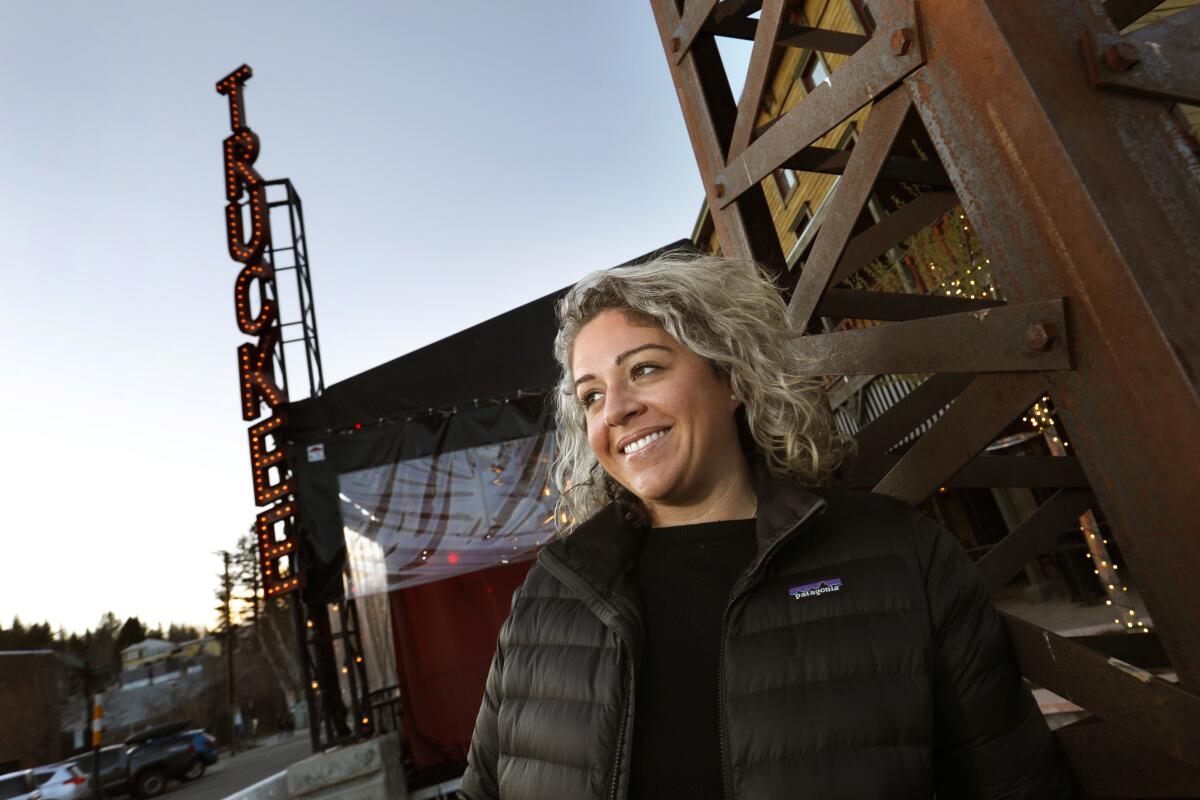

But nothing could have prepared them for the sudden influx in residents, said Anna Klovstad, Truckee’s mayor.

“You can’t build housing overnight,” Klovstad said. “It’s still too little, too late.”

The city’s location also presents particular problems when workers have to live out of town. One private school, for instance, has to shut down when snowfalls close Interstate 80 because its teachers are unable to commute into Truckee from Reno, 30 miles east.

Hostility to the influx in residents over the last year has sometimes boiled over. Klovstad said she received multiple emails from constituents demanding the city close the exits to Truckee on I-80 to keep people from being able to access the community.

Klovstad said she often reminds Truckee residents that just about everyone also migrated from somewhere else before moving in. While some of the transgressions of the town’s culture are annoying, she said, other issues are much more pressing.

“We don’t like to be honked at. It’s not what we do,” she said. “But it’s a whole other level to be kicked out of your house because you can’t afford to live here.”

Elizabeth Stinson is now facing that reality. She moved to the Tahoe area in 2009, working four jobs in hospitality before becoming a restaurant manager. Two years ago, she left her full-time job to study to become a teacher and was paying the bills with three waitressing gigs — until she lost them all on the same day as the pandemic emerged last spring.

Stinson was unable to pay her $1,500-a-month rent and immediately received an eviction notice from her landlord. She was able to stay for a few months but ultimately moved in with a friend in Truckee. It’s been impossible, she said, to find anywhere else.

“Our friends are turning on each other competing for housing,” said Stinson, 41. “By the time you find out about a place, landlords have like 65 emails about it. You have to give your entire life story to them, and then they don’t even respond. It’s so humbling.”

As the pandemic eases, a key factor in determining if the boom in Truckee and other vacation towns will become more permanent depends on employers. A recent survey by Zillow of more than 100 economists and real estate experts found that 95% believe that increased preference among employees for some form of remote work will persist, pulling people to spend more time in outdoor destinations.

With Facebook allowing workers to stay remote indefinitely, Jarson plans to remain in Truckee full time. His friends would like that, too.

“It’s amazing how many friends are now like, ‘Ben, it’s been a while since we caught up,’” he said with a laugh. “‘How about we meet at your Tahoe house?’”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.