What defines ‘cool’

Few things could be less cool than conducting a scientific study on what it means to be cool, but that didn’t stop a group of researchers from facing the question down anyway.

Their study, “Coolness: An Empirical Investigation,” developed from what sounds like a barroom debate.

“One day, a friend of mine was trying to figure out if Steve Buscemi was cool,” said Ilan Dar-Nimrod, an adjunct assistant professor at the University of Rochester Medical Center in New York. “We couldn’t seem to agree, so being the social scientist geeks that we are, we decided to take it upon ourselves.”

The researchers asked 508 people, ages 15 to 56, to come up with adjectives they associated with the word “cool.” The participants repeatedly used terms like “confident” and “popular,” and, less frequently, “aloof” and “calm.” The researchers concluded that while coolness isn’t necessarily easy to define, people recognize it when they see it.

“Coolness has really two faces,” Dar-Nimrod said. “One is the face of someone like Miles Davis, the other is the face of a person who is considered to be confident and successful and attractive but doesn’t have much of the edginess.”

Social desirability

In every office, school or social group, there are people who exude confidence and make everyone around them feel comfortable — people likely to be called “cool” by their peers simply because they’re so enjoyable to be around.

Emanuel Maidenberg, a psychologist at UCLA, says that people who fall into this category likely have naturally outgoing personalities that predispose them to be admired. Their social nature becomes a positive loop: because they’re so likable, other people are drawn to them. And because other people are drawn to them, they remain popular.

“They become key towards human social connections because of their ability to interact, their interest in it and their social skills,” Maidenberg said.

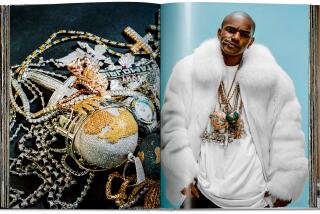

Rebelliousness

The second type of cool identified by Dar-Nimrod and his team denotes a demeanor not unlike the Don Drapers and James Deans of the world: a detached, effortless attitude defined in part by emotional control and a certain unflappable confidence.

Dar-Nimrod describes this type of coolness as “the more historical version,” characterized by “rebelliousness, irony and roughness.”

And while this could come across as posturing, Rebecca Walker, author of the book “Black Cool,” said that ideally it’s generated from a sense of internal calm.

“It’s an intellectual passion, reserve, audacity and grace under fire,” she said. “There’s a profound stillness and a holding within of energy.”

What entices us about people who exhibit this kind of detachment, Maidenberg said, isn’t necessarily who they are but who we can imagine them to be.

“Being aloof and detached is something that is attractive in and of itself,” he said, “but if you don’t interact with somebody or can’t know much about their life, it creates more room for us to develop and project fantasies.”

A West African concept

The notion of cool, according to historians, is not new. Robert Farris Thompson, an art history professor at Yale University, said that it has its roots in West African culture, dating to the Middle Ages.

In an email, he noted that the word “ewuare” — a nod to a West African king from the 1400s — was once used to describe someone who “brought cool (peace) back after a period of civic strife.”

Walker said that many of our modern constructs of cool come from those West African ideas.

“Over the course of American history, mainstream culture has adapted a similar aspect of cool” as the West African notion, she said. “There are words that we wouldn’t have if Africans hadn’t landed on these shores, like ‘cool,’ ‘funky’ and ‘hip.’ ”

Jazz roots

A more modern twist on cool came about during the first half of the 20th century, through jazz. David Schroeder, the director of jazz studies at New York University, said that cool is intrinsically part of the attitude of jazz musicians, as well as the way that the genre evolved.

“Initially, cool was a term meaning that there was hot jazz — lively and exciting,” he said. “Then there was another form that evolved called cool jazz, and cool jazz was more subdued and introverted.”

The jazz community expanded the meaning to style, including sunglasses, sharp clothes and sports cars, Schroeder said.

“Musicians still want to act cool and act separate, to follow their own path rather than find the norms of what culture dictates,” Schroeder said. “People who have passion to be musicians tend to be more individualistic.”

Timothy Parker, who goes by the name Gift of Gab as part of the hip-hop duo Blackalicious, notes that creating music isn’t about becoming someone else but becoming the best version of yourself.

“There is a mystique that the music creates, [and] the music kind of takes you to a place where you’re more free and you have less inhibitions,” he said. “At the same time, I’m still who I am.”

Understanding human behavior

Today, cool is an enduring concept that’s part of our everyday vernacular. But Dar-Nimrod said there are more profound implications to his research as well.

Harnessing the power of the word and the concept could be used to curb excessive drinking, smoking and poor habits around health and self-image, he adds. “We’d like to see what elements in coolness can be used as a tool to create improvement in people’s lives.”

Meanwhile, one big question remains.

“The most frustrating thing about this research is that nine years later, we still can’t agree on whether Steve Buscemi is cool or not,” said Dar-Nimrod. “We have a ways to go before we can give him a coolness quotient.”