Frank Shorter still keeps an impressive pace

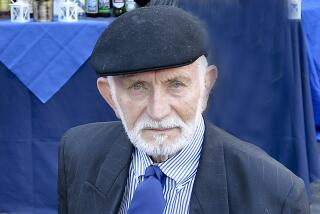

When Frank Shorter won the gold medal in the marathon at the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich, he not only became a household name but also helped create the fitness boom. Pre-Shorter, hardly anyone ran for fitness; post-Shorter, millions did. A Yale grad and trained lawyer who claims to have run 140,000 miles, Shorter’s influence grew as he won a silver medal in Montreal in 1976, led the fight to allow runners to turn pro, won a Master’s duathlon (bike-run) world championship, became the first head of the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency and established himself as the running world’s elder statesman. Today, at a remarkably fit 66, he jets across the country appearing as a featured speaker at running events and will be seen April 21 as a commentator during the Universal Sports Network’s coverage of the 118th Boston Marathon.

Are you still running big miles and competing in age-group races like your fellow marathon legend Bill Rodgers?

No to both. Even though I work out two hours or more a day, probably as much time as when I was running 20 miles a day, I’m not running so much. I’m biking, swimming, doing the elliptical and weights. I run four or five days a weeks for an hour or 45 minutes, but never push it beyond 70% of my max effort, keeping a conversational pace. Of course, you must train harder to race, but I don’t race anymore. Besides, running too hard, too long gives you diminishing returns: You get hurt and tired. I know that mileage takes a toll. I had a hip resurfacing in 2009 and a torn meniscus scoped on my right knee last December.

To stay functional as you age, you have to work the whole body. Weights and intervals are very important. I’ll do four days a week of weights — dips, push-ups, chin-ups, leg presses, squats.

What’s your strategy on diet?

Lots of vegetables and fruit, lots of fish, especially salmon. I have red meat maybe once every two weeks because I think it’s got some essential amino acids that you need. I don’t eat refined sugar but do eat whole grains and granola. Low-carb diets are great if you never want to contract a muscle again. I don’t do any supplements because, as a former chairman of the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency, I know that there’s not enough oversight by the FDA to ensure that they aren’t tainted.

A 2011 Runner’s World magazine story in which you described daily childhood beatings by your father got a lot of attention. Why did you choose to talk about it after so many years?

I realized, when I was in Springfield, Mo., in 2009 addressing a group of troubled kids, that these kids and I belonged to the same veterans organization: abused children. I impressed upon them that they didn’t deserve it, that being treated like this is not normal. I told them that they could save themselves by doing what I did: finding surrogate parents.

Two years later, I briefly mentioned this to an interviewer writing one of those “Where are they now?” profiles of me. When the editor read the story, he called me and said that the magazine wanted to re-interview me to focus more on the abuse my brothers and sisters and I experienced, then corroborate the story with them. After some thought — I didn’t want to violate their privacy — I called the one sister who suffered the worst abuse of all of us. She agreed to talk to the magazine.

What has been the feedback?

Although I didn’t intend to advance an agenda — I’m not a fading rock star trying to jump-start a fading music career — I did like the idea of making a small effort to perpetuate the species. I think I did a good job of raising my own three kids ... . Now almost every time I speak at a running expo, one or more people come up and say that they grew up in similar circumstances. And that’s enough. Because they will spread the word to one or two other people.

You were working the TV broadcast at the Boston Marathon last year when the bombs went off. What’ll be going through your head on April 21?

It’ll be a very emotional show. I don’t know how I’m going to react on the air. Bomb one went off 30 yards from me. I saw a man with no legs being carried off in a wheelchair. It brought back bad memories. I’m probably one of the few people in the world who heard the shots in Munich (from terrorists who killed 11 Israeli athletes at the 1972 Olympics) and 41 years later heard the shots here. Just as in Munich, you realized that if you let them have the fear, they win — so you have to go on.