She’s building Los Angeles’ first solar community fridge. Will it help extinguish hunger?

In early June, my colleague Sam Dean sent me an enthusiastic yet slightly cryptic Slack message: “The fridges are spreading!”

He attached a link to an Instagram post of a refrigerator in front of what looked like a machine repair shop, the words “Comida Gratis” flowing across the front in dreamily airbrushed cursive letters.

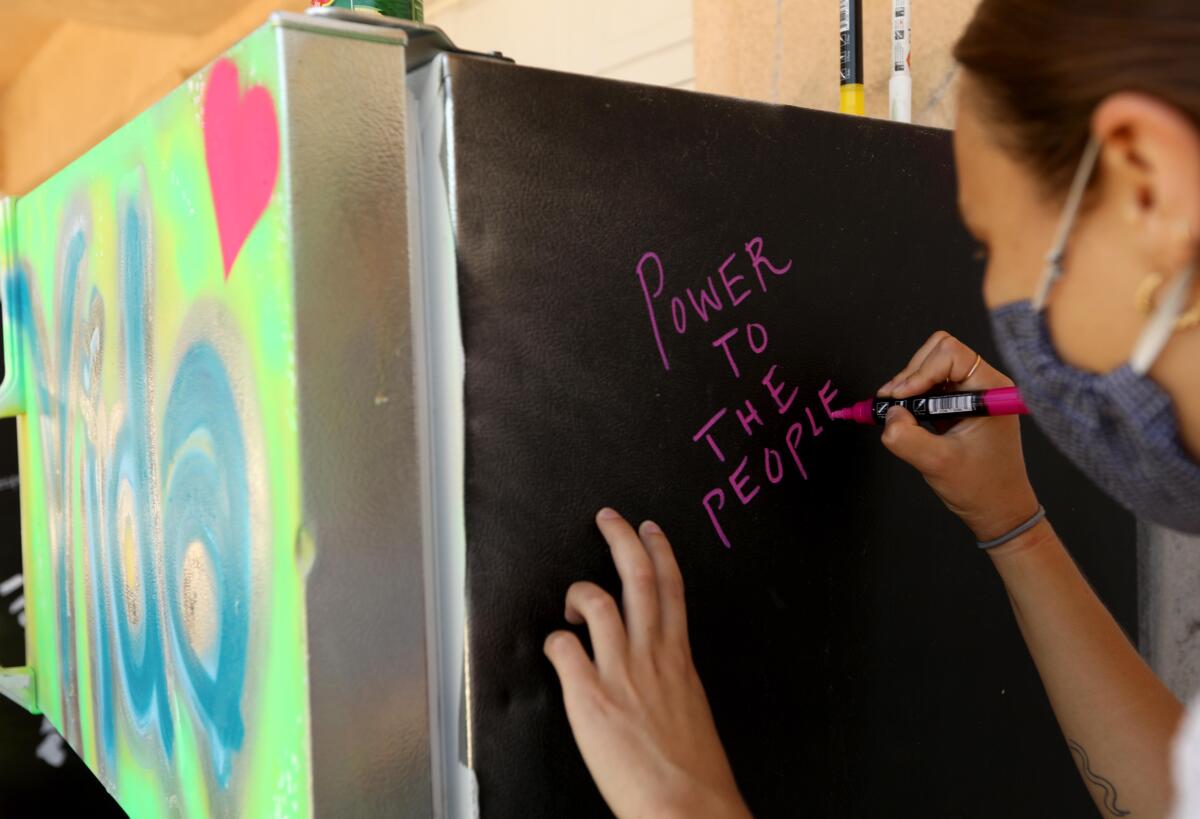

Indeed, if you spent any time driving or walking around Los Angeles this summer you probably noticed the surge of gently used refrigerators popping up on city sidewalks, sometimes decorated with the words “Free Food” in colorful lettering, nearly always stocked with fresh produce, pantry staples — milk, bread, apples — and, sometimes, sanitary items such as soap and tampons.

Free-food fridge programs have mushroomed in cities across the U.S., part of a growing movement of COVID-era mutual aid, mostly volunteer-driven efforts that target people’s basic survival needs not through charitable donations but direct community action.

In Southern California, the most active program is Los Angeles Community Fridges, a decentralized network of volunteers who donate, install, clean, maintain, stock and use community refrigerators. Currently there are 16 active fridges listed in an online directory, hosted by a variety of businesses, community organizations and individuals, some of which regularly broadcast updates on social media about what’s in stock and what needs replenishment.

Reports that city officials recently shut down three community fridges in L.A. highlight some of the challenges these programs face: vandalism; tensions with city officials over alleged safety code violations; and charity-minded upstarts who install fridges in neighborhoods without consulting the people who live and work there.

Brenna “Bee” Burlingame, a recent graduate of USC’s chemical engineering program, has been privately wrestling with these questions since she committed earlier this summer to building what may be L.A.’s first community solar fridge.

A student of nanotechnology who once helped build an autonomous electric vehicle at USC’s Hyperloop lab, she reached out to Los Angeles Community Fridges organizers earlier this summer with the idea to build a simple solar-powered structure that can function in almost any well-monitored outdoor space.

“I’m not inventing anything. We’re essentially building an off-grid house that just happens to be very small and has a fridge inside of it,” Burlingame said.

Using solar energy to power refrigerators is not new; the United Nations began to develop a line of solar-powered coolers and other refrigerator units in the 1980s.

For now, community refrigerators require hosts with access to the power grid; a solar-powered structure could stretch the possibility of where the units are placed and who is empowered to become a host.

Burlingame has been documenting her work in hopes of producing open-source plans for other engineers interested in building solar-powered community fridge structures.

Sourcing is a challenge; Burlingame is building the fridge structure entirely from used, recycled or donated lumber, batteries and solar panels (most mutual aid projects avoid cash donations). A bigger concern, she said, is making sure the solar fridge is placed in a community that needs and wants it. It will require building relationships in the community that ultimately adopts it, she said.

“The solar fridge is just another tool that the L.A. Community Fridges network can use to serve any community who expresses that they want a fridge,” Burlingame said.

Because they will be equipped with several highly visible components — including solar panels and a battery tank — solar fridges will probably be more vulnerable to vandalism and other forms of interference, Burlingame said.

“The highest priority as far as placement criteria is making sure there’s a couple of dedicated hosts that either want to have the fridge on their property or at least walk by it on a daily basis.”

“If there’s ever an issue with the solar fridge, there should be information posted on it so you can call someone. And you already know the person who’s going to show up to help because you’ve already had rapport with that person,” she added.

Working on L.A.’s first solar community fridge project has allowed Burlingame a sort of creative freedom she said many of her USC cohorts aren’t getting.

“Most of my classmates are either going into graduate school or they started to work for pharmaceutical companies, oil companies and military contractors,” she said, adding, “I knew I wasn’t going to be successful in those environments. I decided I have to pave my own way.”

Burlingame’s way involves drafting plans in her Los Angeles workshop, where she designs, catalogs parts, tests batteries and communicates with volunteers on the highly active L.A. Community Fridges Slack page. (Prospective community fridge volunteers can also sign up through the group’s Instagram, @lacommunityfridges).

She envisions founding an “ethical engineering collaborative” to help tackle seemingly intractable problems such as food insecurity in meaningful ways.

“California is the fifth-largest economy in the world,” she said. “We have more than enough resources, money and agricultural productivity to feed everyone in California three organic meals a day.”

And she imagines a future in which solar could play a big role, wondering: Has anyone ever deployed a network of solar fridges for the purpose of dissolving the food distribution barrier completely?

In this moment, when people across the country are building informal networks to feed one another, is the idea so crazy?

“The revolutionary thing is how all these things have come together for the goal of actually, legitimately, feeding Los Angeles,” she said.

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.